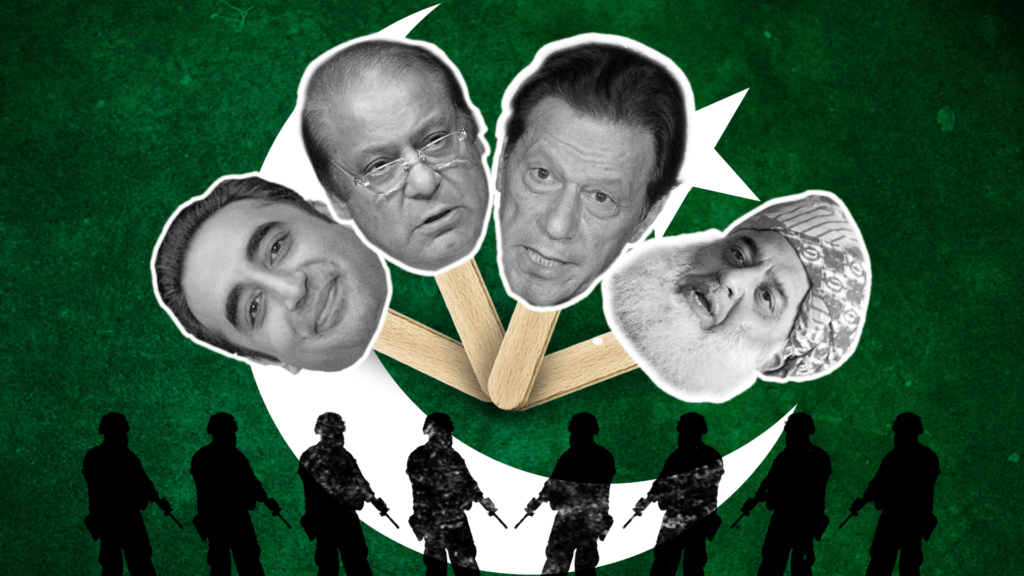

The Pakistan military does not want a genuinely popular civilian political leader in power

For almost 34 years, Pakistan has been under direct military rule. : Gilbert Drean CCBY4.0

For almost 34 years, Pakistan has been under direct military rule. : Gilbert Drean CCBY4.0

The Pakistan military does not want a genuinely popular civilian political leader in power

As Pakistan gears up for its general elections on February 8, the fate of the country’s democracy hangs in the balance. Concerns about the fairness and transparency of the electoral process are mounting.

The rejection of the nomination papers of most candidates of the Pakistan Tehreeq-e-Insaf party (PTI) and some other parties has sparked debates about the legitimacy of the polls. There are worries about the overall fairness and legality of the electoral process, heightening Pakistan’s challenges to political stability.

Achieving political stability is paramount to addressing numerous challenges, including a weak economy, soaring inflation and escalating foreign debt.

Pakistan does not have a good track record of free and fair elections.

For almost 34 years, the country has been under direct military rule. When not in power, the military has resorted to political engineering to manipulate poll outcomes or dismissed governments that were not to its liking.

The military propelled the PTI to power in 2018, creating a leader in Imran Khan, who lacked prior governance experience.

Imran’s political rise and downfall have been remarkable.

The PTI, barely visible on the political scene in 2008, made substantial gains by securing 17 percent of the popular vote in 2013, increasing it to 32 percent in 2018. However, this may not necessarily be the strength of the PTI’s support base, as the elections in 2018 were rigged in its favour.

The 2018 elections were Pakistan’s second successful democratic transition – one political party handing over power to another without being dismissed. It possibly portends the future of electoral democracy in Pakistan – a political system in which the military will not derail democracy but will simply “guide” it.

Imran claimed he and the military were on the same page early in his tenure. However, differences with the Army arose over choosing the successor to the then Director General of Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Lt. Gen. Faiz Hameed. The Army Chief, General Qamar Javed Bajwa, also distanced himself from Imran’s anti-US stance.

The economic mismanagement under Imran’s government was also an issue. Pakistan’s GDP fell from USD$315 billion in 2018 to USD$292 billion in 2022.

Imran’s politics did not gel with the military. His government was ousted from power in a no-confidence motion in April 2022. His removal, Imran believed, was due to a foreign conspiracy (read, US). Urging his supporters to engage in peaceful protests, he garnered significant traction with his anti-establishment and anti-American narrative.

The PTI has been a disruptive force in Pakistani politics for some years now. The zenith of the party’s disruptive politics unfolded on May 9, 2023, marked by attacks on military installations and public property, shortly after Imran’s arrest by the security forces.

Since then, the military has made a systematic effort to break and weaken Imran’s party.

Imran is currently incarcerated, and attempts to marginalise the PTI have given rise to splinter parties like Jahangir Tareen’s Istehkam-e-Pakistan Party and Pervez Khattak’s PTI (Parliamentarians).

The party has been deprived of its “cricket bat” election symbol on the grounds that its intra-party polls were unconstitutional, bringing into question the impartiality of Pakistan’s Election Commission. Party members have been intimidated and faced obstacles in filing nomination papers, and the police have targeted their families.

The way the military has gone after Imran and dismantled the PTI, it is clear that it will never allow him to return to power.

In 2018, Imran was the flavour of the electoral season. Ironically, in 2024, it is his bete noir, Nawaz Sharif of PML (N).

In the 2018 elections, the military did not want Nawaz Sharif back in power and did its best to weaken the PML (N). Ironically, in 2024, it does not wish Imran Khan to return to power but wants Sharif instead.

The Pakistan military does not want a genuinely popular civilian political leader in power backed by an electoral mandate.

It also wants a civilian government that would protect the core interests of the military in policy-making.

The military would no longer like to be burdened with the responsibilities of power. Instead, it prefers a “guided democracy” – a formal democratic structure maintained and legitimised through elections.

This façade of democracy shrouds the actual role and power of the military as an institution in the civil-military equation. Imran had to be jettisoned because he began to undermine the arrangement with the army that had catapulted him to power.

Now, with Imran contained and the probability of his returning to power being almost non-existent, the PML (N) leadership is actively working on building a future ruling coalition. However, the party lacks a concrete programme to address Pakistan’s significant challenges.

The PML(N) appears to be stuck in the past, with the list of probable candidates dominated by old faces, particularly from the Sharif family.

The performance of the Pakistan Democratic Movement under the prime ministership of Nawaz Sharif’s brother, Shehbaz Sharif, was lacklustre. It raises questions about what the PML (N) has to offer to deal with Pakistan’s economic and security challenges that would be new.

Therefore, the prospect of these elections bringing about political stability and tackling the fragile economic situation remains uncertain.

Pakistan faces formidable economic challenges, having narrowly averted default in 2023. Managing debt servicing poses a significant challenge, with projected figures reaching USD$25 billion for the financial year 2024-25 and USD$23 billion for 2025-26.

While external borrowings offer temporary relief, lasting stability necessitates structural reforms, including fiscal responsibility and a reduced dependence on external aid. Whether a “selected government” will have the freedom and autonomy to tackle these challenges, bring about political stability, and improve democratic governance in Pakistan remains to be seen.

Ajay Darshan Behera is Professor at MMAJ Academy of International Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.