Indonesian researchers have tested a cheaper way of monitoring antimicrobial resistance that could be a key tool for developing countries.

Testing for antimicrobial resistance does not have to be expensive. : “Tuberkulosis Menjadi Masalah Kesehatan yang Belum Tuntas” by KKP Unpad CC BY 4.0

Testing for antimicrobial resistance does not have to be expensive. : “Tuberkulosis Menjadi Masalah Kesehatan yang Belum Tuntas” by KKP Unpad CC BY 4.0

Indonesian researchers have tested a cheaper way of monitoring antimicrobial resistance that could be a key tool for developing countries.

Indonesian researchers have tested a cost-effective, relatively quick method of measuring changes in antimicrobial resistance that could help developing countries fight a problem seen as a global threat.

Instead of sticking to an approach that emphasises the need for intensive laboratory testing that might not be practical in many countries, they assessed lot quality assurance sampling — a system where a population’s antimicrobial resistance can be assessed using smaller sample sizes.

That’s good news for the G20 after health ministers committed to tackling the threat comprehensively at their meeting last month.

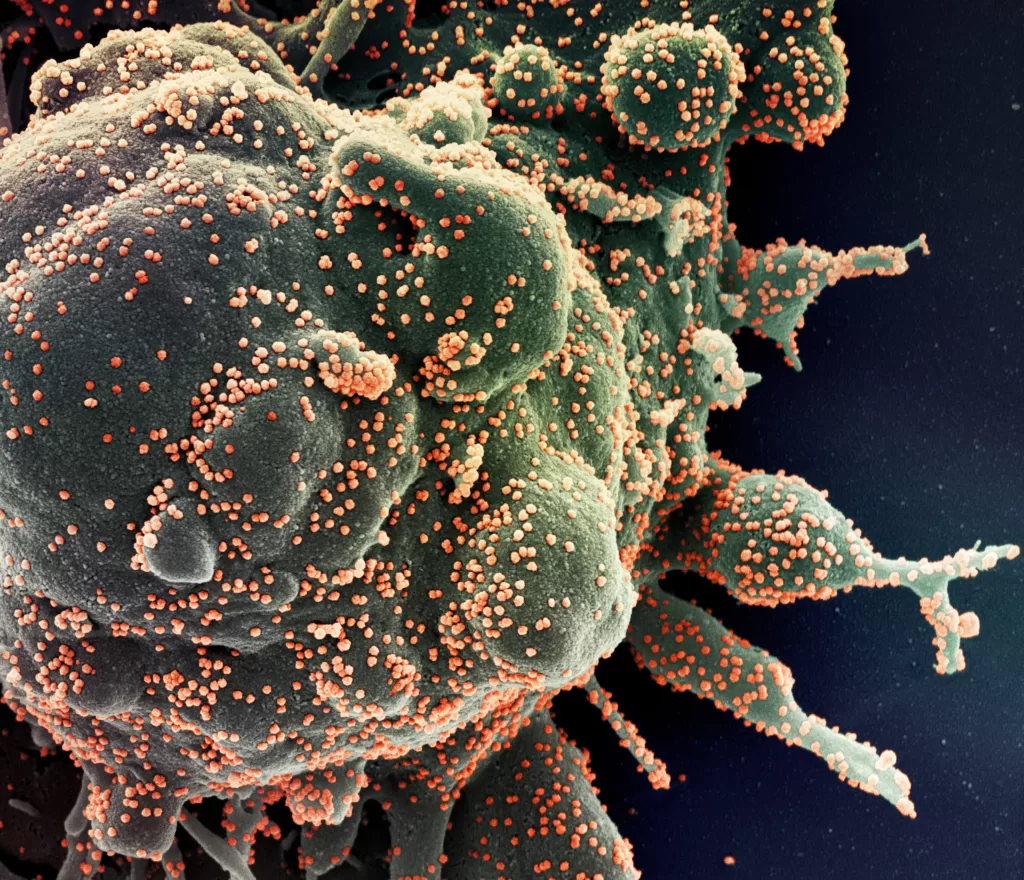

Antimicrobial resistance is the ability of microbes to block the effect of drugs that are meant to kill them. This makes infections harder to treat and can lead to longer hospital stays, more expensive care and increased risk of death.

The high level of antimicrobial resistance in Indonesia is now becoming a silent pandemic.

The United Nations has warned the rise of ‘superbugs’ could kill 10 million people a year globally by 2050 and be a drain on the world economy.

Like in many other countries, the improper use of antimicrobial drugs and other factors that trigger resistance, such as poor sanitation and air pollution, are prevalent in Indonesia.

In 2015, the 68th World Health Assembly adopted the Global Action Plan on antimicrobial resistance. It emphasises the importance of enhanced global surveillance, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where it is a major concern.

One of the key pillars of the Global Action Plan is the support for national strategies through improved global surveillance. The proposed global surveillance system aims to estimate the prevalence of resistance by using laboratory testing of clinical samples.

However, this approach is not always practical in developing countries because of their limited access to quality microbiology diagnostics.

Population-based surveillance is a preferred strategy, but it is also time-consuming, labour-intensive and costly.

That means many regions need a rapid, feasible and affordable surveillance strategy.

Indonesian researchers found an alternative approach: they tried lot quality assurance sampling.

This method, which was originally developed in the manufacturing industry to assess batch quality, involves classifying a population as having a high or low prevalence of antimicrobial resistance based on a small sample size.

It has proved to be more practical and cost-effective than conventional population-based surveillance.

The Indonesian research applied the lot-based approach to assess the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in patients with suspected urinary tract infections.

The researchers wanted to estimate the test characteristics for identifying populations with a high prevalence of resistance in urinary tract pathogens, provide lot-sampling classifications for 15 antibiotics in 11 different settings and estimate the cost of implementing lot sampling in a single health facility.

The testing was done in the Indonesian cities of Medan and Bandung, and the exercise was repeated 1,000 times for each of the 13 lots.

They found lot testing was 98 percent effective in correctly identifying populations with a high prevalence of antimicrobial resistance.

Overall, the researchers were able to show that lot quality assurance sampling is a promising approach to efficiently estimate antimicrobial resistance prevalence and guide treatment decisions, especially in resource-limited settings.

By significantly reducing sample size requirements and increasing efficiency, lot-based surveillance could significantly contribute to public health efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance worldwide.

The findings are particularly significant in the context of the growing importance of surveillance as a crucial tool for antimicrobial stewardship.

Previous studies on drug resistance have shown lot-based surveys are effective in identifying local variations in drug-resistant tuberculosis and assessing the prevalence of transmitted drug resistance in HIV.

This style of survey could be implemented at sentinel sites, enabling regular assessments of changing trends, intervention impacts, or early detection of resistance development after introducing new drugs.

This utility is particularly beneficial in settings with limited microbiology capacity or where empirical treatment is common, such as primary care settings globally.

The cost of the lot-based surveys, including 15 antibiotics, ranged between US$403 and $514 in the 11 sites studied — relatively cheaper than conventional testing regimes.

Despite some limitations, including the need for careful site selection and ensuring proper laboratory accreditation and quality control, lot quality assurance sampling shows promise in providing valuable information on antimicrobial resistance for both clinicians and policymakers.

Ida Parwati is a professor at the Department of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran in Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia.

This work was funded by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences as part of the Scientific Program Indonesia–the Netherlands (SPIN).

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.