With digital attacks on journalists increasing, Indonesia's press council formed a task force in response. But could the country's laws be part of the problem?

Digital attacks on journalists in Indonesia are increasing. : Towfiqu Barbhuiya via Unsplash Unsplash License

Digital attacks on journalists in Indonesia are increasing. : Towfiqu Barbhuiya via Unsplash Unsplash License

With digital attacks on journalists increasing, Indonesia’s press council formed a task force in response. But could the country’s laws be part of the problem?

The 2022 attacks on media organisation Narasi have been the biggest and worst in Indonesian history.

Thirty-eight current and former employees had their mobile phones hacked, some of the company’s social media accounts were targeted and its website was subjected to a denial-of-service (DoS) attack.

Unfortunately, Narasi is far from an isolated case.

Online feminist news organisations Magdalene and Konde have also experienced digital attacks.

Personal information belonging to one of Magdalene’s journalists was hacked and she was harassed by people sending her pornographic images and demeaning messages about women.

With digital attacks on journalists increasing, the Indonesian press council last year established a digital violence taskforce to ensure the legal process is followed when journalists report digital violence cases to authorities, victims are supported in their recovery, and to try and prevent future cases against individual journalists and media organisations.

But Indonesia’s own laws and their implementation may be working against these efforts to protect journalists and safeguard press freedom, particularly in the digital space.

For example, the number of people charged under Indonesia’s notorious Information and Electronic Transactions Law (ITE Law) has tripled from 74 cases during President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s second term (2009-2014) to 233 cases during the first term (2014-2019) of President Joko Widodo.

Of the 241 people charged during Widodo’s first term and the first year of his second, 82 of them were accused of insulting the president according to SAFEnet and Amnesty International.

The Ministry of Communication and Information requires all private electronic systems operators to register with the government, essentially forcing them to accept national jurisdiction over their content and user data policies and practices.

This regulation becomes a repressive instrument that contradicts and even violates human rights, because it authorises the government to block access to online information.

For journalists, this rule has the potential to affect citizen journalism platforms and can even target mass media outlets.

It is not surprising that such provisions have an impact on journalistic work and are contradictory to efforts to advance the protection of press freedom.

Journalists continue to be imprisoned under the ITE Law, while digital attacks such as hacking, doxing and other forms of online persecution continue without victims being able to seek any meaningful legal accountability.

Neither cases nor people are brought to the court. There seems to be a systematic impunity for those who commit digital attacks.

The situation has been further exacerbated by the ratification of the new criminal code in 2023.

The Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) identified 19 articles in the criminal code that directly threaten press freedom in Indonesia, including the crime of insulting the government and the crime of attacking the honour or dignity of the president and the vice-president.

Under such repressive laws all acts of power appear legitimate, and the law becomes little more than a political mechanism to support the interests of the elite.

Freedom House noted that internet freedom in Indonesia was declining due to increasing pro-government information and propaganda, as well as barriers to access, content restrictions and violations of user rights.

Journalists continue to face criminal charges, harassment and technical attacks due to their online work, and the Indonesian government is suspected of buying spyware to surveil them.

This led Freedom House to categorise Indonesia as only “partly free” for freedom on the net.

The weakening of press freedom in the digital realm goes hand in hand with the strengthening of authoritarian power politics, both those involved in and those allowing such digital attacks to occur.

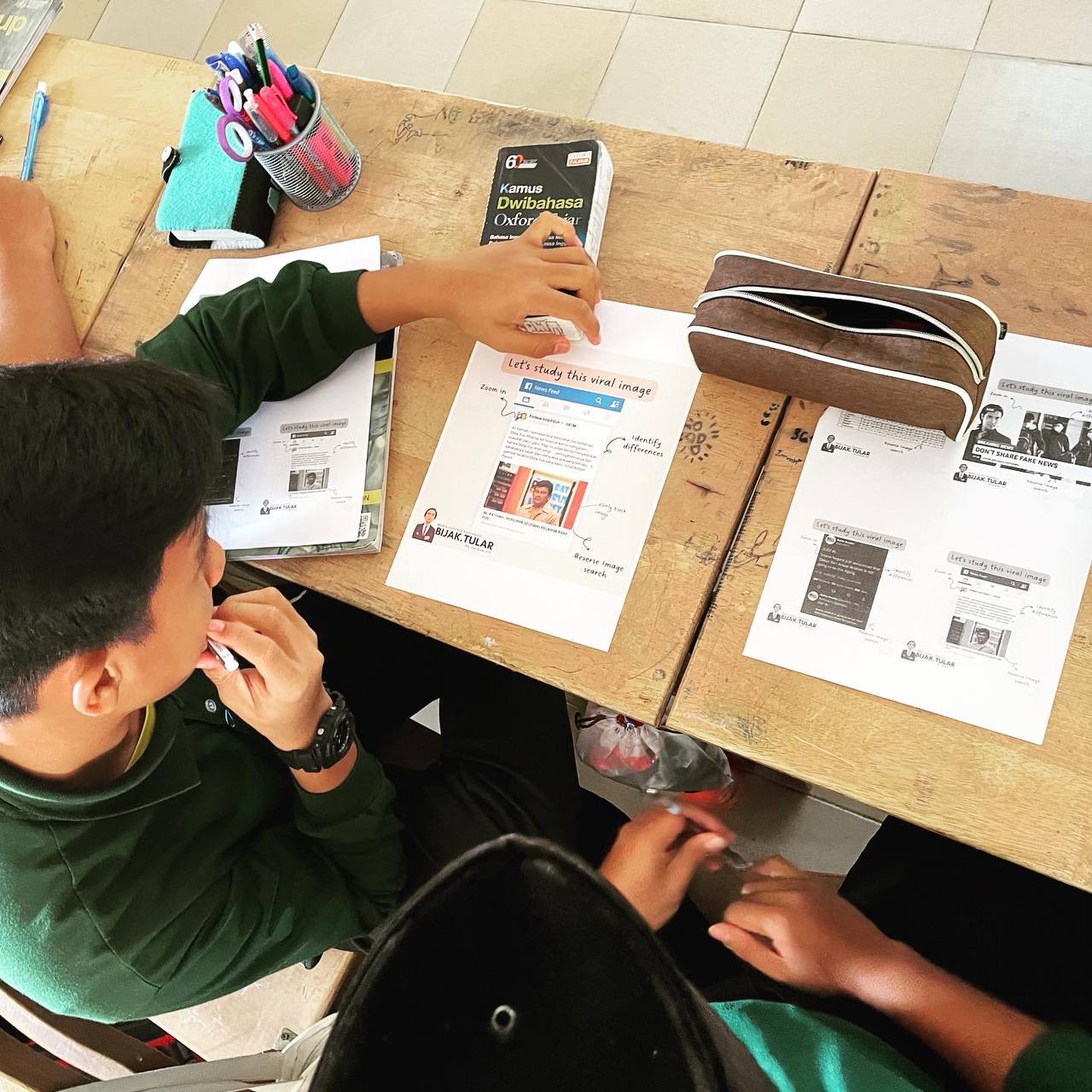

In their efforts to guard against digital attacks, journalists are learning how to digitally protect themselves.

There is also hope that through the newly enacted data protection law they will be able to follow up the illegal distribution of their personal data or information and seek legal recourse.

Herlambang P. Wiratraman is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Law, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, a secretary general of the Indonesian Young Academy of Science (ALMI), and Director of Law and Human Rights at the Institute for Research, Education and Information on Economy and Social Affairs (LP3ES). His work focuses on constitutional law, human rights and freedom of expression.

Dr Wiratraman declared that he has no conflict of interest and is not receiving specific funding in any form.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.