Good intentions alone will not ensure a free and fair election

Although Bangladesh’s election commission has a plan to meet the challenges to holding free and fair elections, its implementation seems patchy.

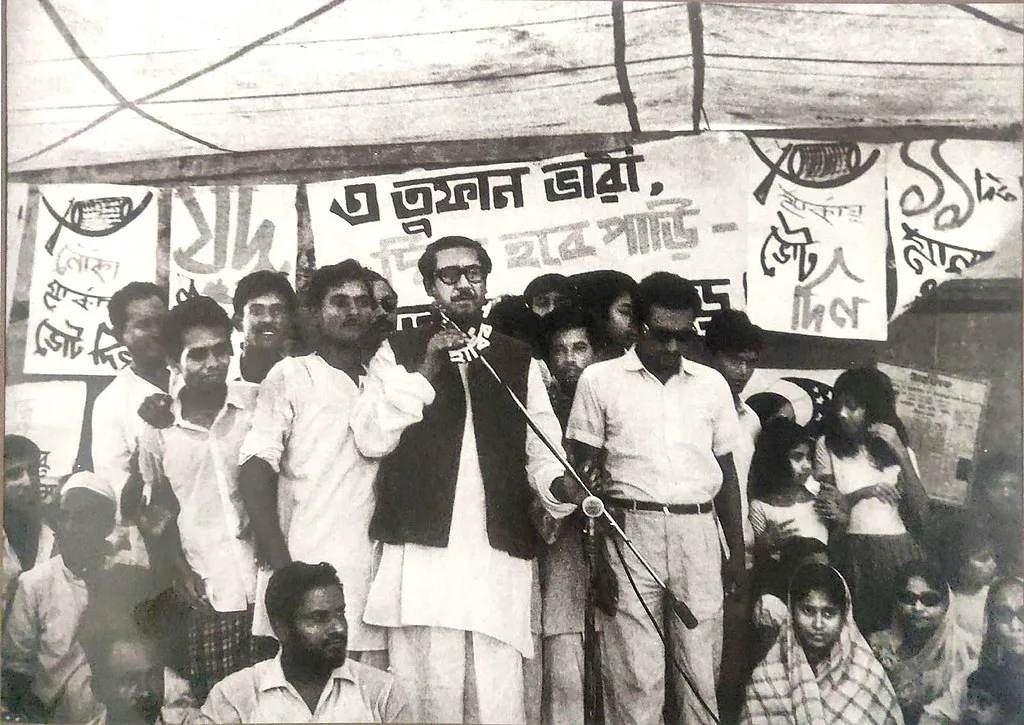

Bangladesh’s election commission has been accused of bias in the past and is facing a credibility crisis on the eve of the January 7 poll. : Wasiul Bahar CCBY4.0

Bangladesh’s election commission has been accused of bias in the past and is facing a credibility crisis on the eve of the January 7 poll. : Wasiul Bahar CCBY4.0

Although Bangladesh’s election commission has a plan to meet the challenges to holding free and fair elections, its implementation seems patchy.

There is unprecedented indifference from Bangladesh civil society to the general election scheduled for January 7. Civil society organisations such as Shushasoner Jonno Nagorik and the Bangladesh Studies Forum do not see the election as inclusive.

Of the 44 registered political parties only 29 are competing. The rest, led by the main opposition party, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), are boycotting the polls, demanding the election be held under a neutral caretaker government.

Among those contesting the polls, the party in power, Bangladesh Awami League (AL) is the largest with a nationwide structure and presence. The others, such as the Bangladesh Jatiyo Party either have limited regional appeal or are far too small to influence the outcome. Some have been launched recently with no tested public support.

A unique feature of the election is the large number of independent candidates.

According to the election commission, 436 independent candidates are in the fray. They are believed to be dummy candidates put up by the AL — they are mostly ex-AL MPs and local leaders who failed to secure the party’s nomination — to suggest a robust contest.

The record of national elections in Bangladesh under the AL government has been tainted with allegations of a lack of fairness and transparency. Even the election commission has been accused of bias in the past. The same goes with the current election commission as it is also facing a credibility crisis.

The present election commission, however, has affirmed its commitment to hold the poll in a free and fair manner. It has identified several challenges and proposed actions to overcome them. However, it seems it’s already been hobbled by inadequate implementation.

Following a meeting of the Chief Election Commissioner with the Chief Justice of Bangladesh on 1 November 2023, the Ministry of Law and Justice issued a notification to establish an electoral inquiry committee in each of the 300 parliamentary constituencies.

Each committee, comprising district judges from each constituency, will be empowered to investigate election-related offences, violations of the Election Code of Conduct, obstructions to a free and fair polling process and other irregularities. These committees will report directly to the commission.

The commission, under the powers accorded by the Article 91 of the Representation of People Order 1972, also adopted rules for the observation of election by the registered local observers called “Nirbachon Porjobekkhon Nitimala (Election Observation Rules) 2023”.

The aim is to let election observers see if there are any shortcomings in the polling process and submit their reports to the commission.

However, closer scrutiny shows these rules have restricted the power of election observers – disallowing observation inside polling booths and restricting time they can spend at an election centre.

Around 180 election observers from 35 countries have reportedly applied for permission to the commission. The commission has provided guidelines for international election observers and foreign media governing their visits to election centres subject to a written approval from the election commission.

However, to enter a particular centre/polling station/booth they require the permission of the presiding officer of that polling centre. Individuals working with international organisations and diplomatic missions based in Bangladesh will be considered on a par with local observers and do not need to register themselves with the election commission.

Media will be provided support in collecting information and broadcasting/ publishing it. They have been allowed to enter election centres with local and foreign journalists being treated equally.

The commission has also formulated a plan for the recovery of illegal arms and issued orders for the surrender of even licensed weapons before the election.

It has proposed setting up CCTV cameras in every election booth, the deployment of a sufficient number of police, a mobile election monitoring force with executive magistrates after the declaration of election schedule and the appointment of returning officers mostly from the election commission staff.

However, the implementation of the plan has been patchy.

For example, no measures have been taken to recover illegal arms or ensure the surrender of legal arms before the election. This in itself constitutes a big threat to holding a free and fair election.

Similarly, while campaign finance and electoral expenses are sought to be regulated, no notice or promulgation has yet been issued to prescribe an upper limit.

As for controlling any misconduct by the candidates, the election commission has only reiterated the rules governing the conduct for political parties and candidates under the Representation of Peoples’ Act.

Their violation will be considered a punishable offence. It remains to be seen how it will be implemented in practice.

Nakib Muhammad Nasrullah is Professor in the Department of Law, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.