Bangladesh is slipping towards elections that may not be free and fair and will undermine its democratic future.

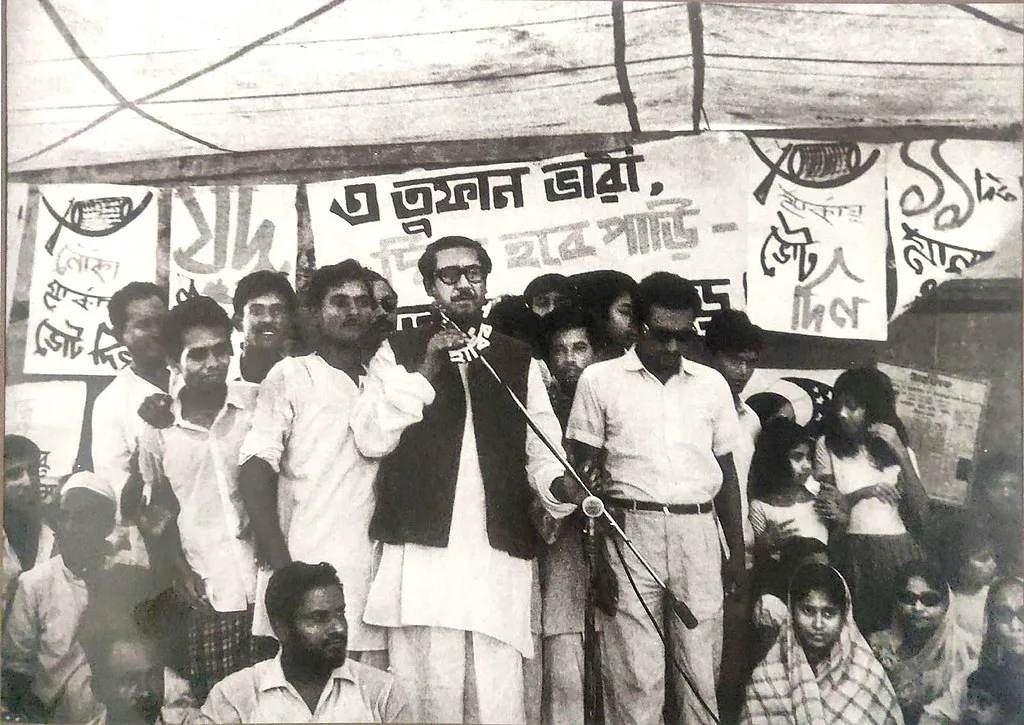

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (centre with glasses) was not willing to take home anything short of an endorsement of his legitimate electoral victory in the general election of 1970, paving the way for the establishment of Bangladesh. Public Domain

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (centre with glasses) was not willing to take home anything short of an endorsement of his legitimate electoral victory in the general election of 1970, paving the way for the establishment of Bangladesh. Public Domain

Bangladesh is slipping towards elections that may not be free and fair and will undermine its democratic future.

Free and fair elections were singularly responsible for the birth of Bangladesh.

The nation’s founding father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, did not want secession from West Pakistan — at that time Pakistan spanned West and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), with India in between.

However, he was also not willing to take home anything short of an endorsement of his legitimate electoral victory in the general election of 1970, which had given his Awami League (AL) party a clear majority.

The Pakistani military and political establishment refused to honour the clear majority he had won. Instead of being appointed the prime minister of Pakistan, Sheikh Mujibur was imprisoned, precipitating an armed insurrection for independence from Pakistan.

Bangladesh’s history, however, seems to have come full circle. The national parliamentary election slated for January 7 risks being neither free nor fair.

The main Opposition, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), is boycotting the election. It has no faith in the incumbent government providing a level –playing field in the elections.

The central demand of the BNP is that the incumbent Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina, resign, paving the way for a neutral caretaker government to oversee the elections.

Caretaker governments in Bangladesh have played a crucial role in democratic consolidation in the past by ensuring free and fair elections. However, the Awami League government changed the Constitution in 2011, doing away with the provision.

Now the Awami League is opposed to the caretaker government system, claiming there is no provision for it, citing the very Constitution it had changed.

Bangladesh today seems to have taken an authoritarian turn. It has slipped from 136th position to 147th in V-Dem’s liberal democracy index between 2015 and 2022, falling below even Turkey (141).

The consequences of democratic decline may be severe.

Justifying democratic backslide citing rapid economic growth may become increasingly more difficult as it may not be easy for Bangladesh to sustain rapid economic growth.

Developed nations may also be unwilling to support Bangladesh’s low-income country status, which has up to now given it a considerable trade advantage. They may not look kindly on human rights violations, adversely impacting Bangladesh’s exports.

Already, foreign direct investment in Bangladesh has fallen from USD$2.8 billion in 2015 to USD$1.5 billion in 2022.

The democratic downslide, however, did not occur overnight.

The original idea of Bangladesh was of a secular and democratic nation. It reflected the Sufi-Lalon philosophy, imbued with secularism and deeply embedded in the tolerant and liberal Bangladeshi worldview. The newly found nation categorically rejected the notions of caste and religious discrimination in public life.

The post-1975 transition, caused by a military coup, however, has eroded the secular nature of the state. It gave rise to Islamic political mobilisation.

Constitutional restrictions on religion-based political parties were revoked, leading to the emergence of Islamic parties, even those that opposed the independence movement. By 1988, Islam was declared the state religion, resulting in Islamist parties gaining prominence, with the largest one forming a ruling coalition with a mainstream party in 2001.

The country’s turbulent political history, characterised by military coups, political assassinations and decades of military-backed rule eventually culminated in a democratic uprising and the establishment of a civilian government in 1991.

This period witnessed festive and participatory elections, fostering a vibrant parliamentary culture in the 1990s.

Despite a return to the parliamentary system, the concentration of power in the hands of respective prime ministers, facilitated not only by their personal charisma but also by constitutional provisions, led to the erosion of democratic institutions.

Personal acrimony between the two main leaders, Begum Khaleda Zia of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and Sheikh Hasina of the Awami League, further contributed to a toxic political culture.

In 2006, amid the BNP’s attempt to leverage the caretaker government system to its advantage, the AL refused to participate in the 2007 general election. A ‘soft coup’ by the military ensued and the country was ruled under the guise of a civilian caretaker government until the end of 2008.

Both Hasina and Zia faced corruption charges, making them ineligible for public office. In the face of an economic crisis and political pressure, the military organised an election in which the Awami League secured a two-thirds majority, which proceeded to swiftly abolish the caretaker system.

Although Sheikh Hasina and her party worked to restore secularism subsequently, her electoral coalition with hard-line Islamic parties like Hefazat-e-Islam and the support for the Quami madrasas have allowed the resurgence of majoritarian religious sentiments. As a result, there is a sense of fear and insecurity among minorities. Increasing attacks on them have deepened it further.

The BNP boycotted the 2013 general election, demanding that a caretaker government conduct the elections. However, it participated in the 2018 election, which was not considered free and fair by large sections of the international community. Prior to that election, the AL government intensified persecution of political opponents, imposed media restrictions and disqualified many Opposition candidates.

Now, the BNP has once again fallen back on the election boycott strategy to ensure a level playing field.

However, the party is currently fragmented and faces a leadership vacuum. The potential for strong political mobilisation is hindered by Khaleda Zia’s inability to actively participate in politics due to her imprisonment and health issues.

Her son, Tarique Rahman, vice-chairman of the BNP, is in self-exile in London after being convicted in several corruption cases.

Furthermore, the BNP’s strong ally, Jamaat-e-Islami, is banned from contesting elections and most of its top leadership has been executed for war crimes. Jamaat had opposed the independence of Bangladesh 50 years ago and collaborated with the Pakistani armed forces, committing mass killings of Bangladeshi nationalists and pro-Independence intellectuals.

It is against this background that impending elections should be judged.

The AL has to decide whether or not it will respect the process of free and fair elections that led to the creation of the Bangladeshi nation. The party, however, does not seem to have learned any lessons from the nation’s nascent history.

How the democratic future of Bangladesh unfolds will depend on the choices that Sheikh Hasina’s ruling AL party makes. Under her leadership, the country may be undermining its very foundational values by slipping towards national elections that are not free and fair.

A S M Mostafizur Rahman is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science, South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University, Germany.

Professor Rahul Mukherji is Chair, Modern Politics of South Asia, South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University, Germany.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.