A focus on viruses as our next pandemic source may divert attention from other serious microbial threats.

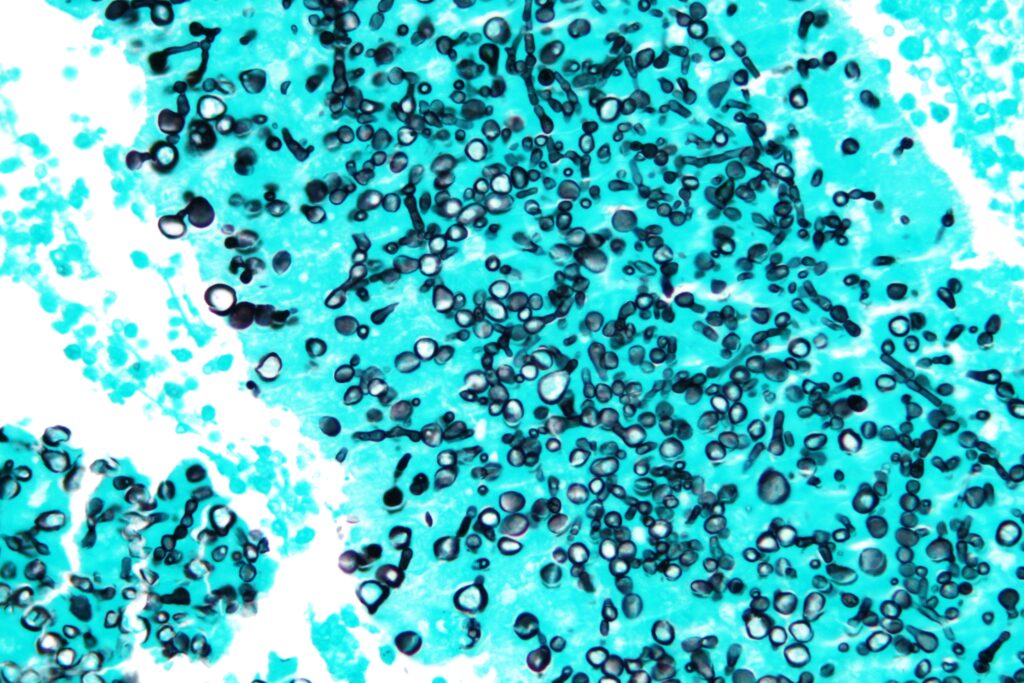

Valley fever is commonly found in soil. : Nephron, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0

Valley fever is commonly found in soil. : Nephron, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0

A focus on viruses as our next pandemic source may divert attention from other serious microbial threats.

We know a lot about the benefits of fungi, including brewer’s yeast, mushrooms, Roquefort cheese and the production of antibiotics such as penicillin. But we know a lot less about the threats to global health posed by fungi, such as those that emerged or re-emerged during the current pandemic.

COVID-19 raised international awareness of the threats posed by zoonotic viruses, which jump from animals to humans. But a singular focus on viruses risks diverting attention and resources away from other microbial threats, particularly pathogenic fungi.

In mid-2021 reports emerged of serious fungal infections in patients with severe cases of COVID-19 and those recovering from the virus. Patients were diagnosed with respiratory infections from a mould called aspergillosis; invasive yeast infections; and, particularly in India, a serious but rare fungal infection, mucormycosis, which leads to prolonged severe illness and death.

Fungi are among the most diverse and versatile organisms on our mouldy planet earth.

In the southwestern United States, and in Central and South America, the fungal pathogen that causes Valley fever, coccidioidomycosis, has long been recognised as a threat to animals and people because it is very commonly found in soil. Cases of Valley fever have increased steadily in the southwestern United States, where it has been considered endemic for more than a decade. But the geographical scale of vulnerable populations is expanding as climate change enlarges the sandy desert zones where the fungus, Coccidioides immitis, grows.

People develop Valley fever after they breathe in dust from soil that contains fungal spores. Climate change causes increasingly frequent droughts, which create more dust, and earthquakes building construction cause the dust to circulate more widely. Together, these factors increase people’s vulnerability to Valley fever.

Ensuring people understand how climate change can impact their health is a key strategy in raising public awareness and motivating political action. The US state of California has been a leading case study in investigating the pandemic threats posed by fungal pathogens, particularly the fungus that causes Valley Fever and its response to climate change. The availability of epidemiologic and climate data, and an understanding of the population’s social vulnerabilities to it, have helped raise public awareness and target at-risk groups.

Candida auris, a multidrug-resistant yeast that causes invasive infection and death, poses one of the most urgent threats of a new pathogen-driven pandemic. It may be the first example of a new deadly pathogen emerging from human-induced climate change because of its simultaneous appearance on three continents — which can only explained by a large-scale environmental shift. First identified in 2009, Candida auris is not known to be directly transmissible from person to person. But its persistence in environmental settings, on surfaces and on everyday objects shows that it is capable of spreading rapidly in hospital settings and natural ecosystems.

Candida auris is an emerging poster pathogen for the One Health approach, which considers the influence of environments shared between humans and animals, and better coordination of local and international strategies for pandemic prevention and response.

Strongly enforced restrictions on the use of antimicrobials (agents that kill microorganisms), such as antifungal treatments in agriculture; integrative surveillance of animal populations, human populations, and environmental systems; and a global health education that begins at community level can help break away from a cycle of fungal zoonotic diseases – particularly as human populations continue to grow against the backdrop of climate change.

Oladele A. Ogunseitan is the UC Presidential Chair and Professor of Population Health and Disease Prevention at the University of California, Irvine.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

This article has been republished for World Zoonoses Day. It first appeared in our Changing climate, changing diseases package.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.