Analysts have suggested there's a secret Chinese government campaign trying to influence the referendum. Here's why that's highly unlikely.

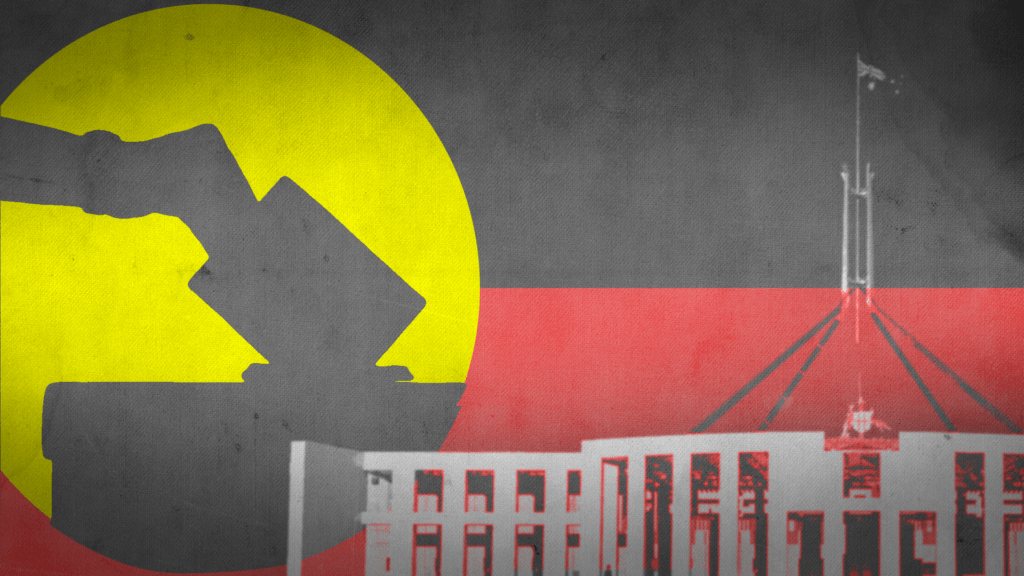

China’s record of influencing Australia through covert social media campaigns has been poor. : AEC Images, Flickr CC BY ND 2.0

China’s record of influencing Australia through covert social media campaigns has been poor. : AEC Images, Flickr CC BY ND 2.0

Analysts have suggested there’s a secret Chinese government campaign trying to influence the referendum. Here’s why that’s highly unlikely.

The barrage of disinformation hitting voters ahead of Australia’s Indigenous Voice referendum has reached such a scale that a world-leading intelligence company is analysing the effort to deceive voters.

That led to reports China might be trying to interfere in the referendum.

There are good reasons why Chinese-sanctioned interference is unlikely but — even if true — they’ve failed to make a mark. There are far more serious social media disinformation threats coming from closer to home.

The claims on China gained prominence when Recorded Future, a firm with a reputation for accuracy and dispassionate analysis, identified many Australia-based disinformation threats pushing bad-faith agendas, including conspiracy theorists, political activists, neo-Nazis, anti-Semites and white supremacist groups.

But it also made a passing mention of commentary made by two analysts at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), published in July, which alleged interference in the referendum debate by a secret Chinese government social media campaign.

A month after ASPI’s report, the claims appeared in The Daily Telegraph, the largest-selling newspaper in Sydney.

Typically, such campaigns by foreign governments are hard to trace. The most serious form is a trolling campaign, where the perpetrators set up elaborately organised ‘’troll farms’’.

These farms produce false or misleading reports, then feed the reports to social media platforms for automated delivery and maximum damage against their targets, usually political leaders.

At a lower level, campaigns can have a ‘nuisance effect’, sowing confusion over key political issues. It’s a form of harassment from an unfriendly country.

According to Australian Strategic Policy Institute researchers, this is what could be happening with Chinese interference in the referendum. They say the aim is to add confusion.

The tactics included experiments with pushing negative media stories, often intertwined with disinformation.

They also said the Chinese campaign narratives support claims that “Australia is a racist and sexist society that suffers from systemic discrimination”.

The analysts did not claim that China was taking sides in the referendum.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute has been accused of spreading its own disinformation in some of their reporting on China, with one researcher calling it the ‘tabloid think tank’.

Australian scholars take issue with some of the think tank’s alarmist coverage of China and its sources of funding, which include the Australian defence department, allied governments and, to a small extent, arms manufacturers.

However, it also has many defenders, evidenced by the support of leading governments and its many partners worldwide. Its record in some areas of China research, such as the suppression of Uighurs in Xinjiang, is world class.

Its story about Chinese interference in the Australian referendum was mentioned in the Record Future report.

Recorded Future offered no endorsement or critique of the Australian think tank’s commentary, but its reference on the reputable platform lent it credibility.

But, just like the policy institute’s commentary, Recorded Future didn’t assess the effect Chinese interference could have, beyond saying the alleged perpetrators might have been content simply sowing confusion.

The policy institute’s report acknowledged that most of the covert Chinese social media accounts in the referendum campaign have only attracted minimal engagement at best.

This is likely the case, but it raises the question of whether the low-level, ineffective activity was worth the attention.

China is an intelligence state: if there is a covert way to operate, it will do so. China has been increasingly active in its covert social media operations, but there’s little evidence to suggest such campaigns have helped China achieve its policy goals.

As recently as 2021, China’s ability to exert influence abroad through covert social media campaigns was assessed as “relatively rudimentary“.

Instead, China relies on its rich set of diplomatic and political tools — propaganda, traditional and economic coercion and legal powers, among others.

If China wanted to harm Australia’s interests internally or externally, it wouldn’t rely too heavily on social media. It would use more direct and powerful ways to inflict hurt, like its recent trade restrictions.

China’s expanded covert influence efforts in Australia have hurt its reputation in Australia more than it has helped.

According to Lowy Institute data, positive views of China in Australia plunged on the measure of Australia’s ‘’best friend in Asia’’ from 29 percent in 2014 (of 1150 surveyed) to 7 percent (of 2077) in 2023.

China’s reduced reputation has been mirrored around the Western world. China’s covert influence campaigns do not appear to help its foreign policy.

It is more likely that the alleged interference noted by the Australian think tank and Recorded Future comes from trolls and hackers who occasionally take on work from the Chinese government.

But it is highly unlikely the Chinese government ordered the actions of these particular trolls in the referendum campaign. The referendum is barely on the radar of Chinese leaders.

Even China’s hardline and hostile news outlet, the Global Times, used an editorial on 7 September to praise the “more pragmatic adjustment by the Labor Party government” in bilateral relations.

If China deploys its trolls on Australia, it would be to undermine the growing military alliance between the United States and Australia. As the Australian Strategic Policy Institute points out, Australia is often a target of such campaigns because it is seen as a leader of the ‘war with China’ debate.

If Chinese-linked trolls and hackers are behind any referendum interference, they are more likely to be acting independently from government direction.

Efforts to manipulate social media from abroad will have almost zero effect on the referendum outcome.

There are too many other actors domestically who will be far more successful — the effect of someone like the potential interference of neo-nazis and white supremacist groups flagged by Recorded Future outweighs any foreign interference.

Over the past decade, China’s record of influencing Australia through covert social media campaigns has been poor.

That doesn’t mean Australia is immune to foreign influence campaigns.

A 2022 federal election foreign influence campaign was foiled by ASIO, while Russia’s IRA troll factory infiltrated Australian discourse around the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight MH 17, which killed 298 passengers — including 38 Australians.

Disinformation campaigns on social media can be a grave threat.

In September, the Australian Electoral Commission expressed concerns over the time it takes social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter, to take down misleading content.

China’s strategic interest in Australia’s Indigenous community has transformed over the past 60 years.

In 1972, just before Australia’s diplomatic recognition of China and amid its Cultural Revolution, China hosted and paid for nine Aboriginal activists to visit the country. It aligned with China’s long-standing policy of supporting ‘radical movements’ and championing anti-colonialist groups globally.

In 2022 China attacked Australia for its record of human rights abuses against Aboriginal people. It called for the UN to investigate and bring perpetrators to justice.

In a period of cautious rapprochement with Australia after years of deep freeze, it is hard to imagine that the Chinese government would endorse attempts to destabilise the referendum.

The most concerning element of referendum disinformation is the sheer scale of the tactics being deployed across online communities by groups of Australian origin.

Greg Austin is an Adjunct Professor at the Australian China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney. He has led research programs for international think tanks on cyber policy and published several books on China’s cyber power.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.