Polling is back in vogue during the Voice referendum debate and those results — rather than the substance of the debate — could influence the way some vote.

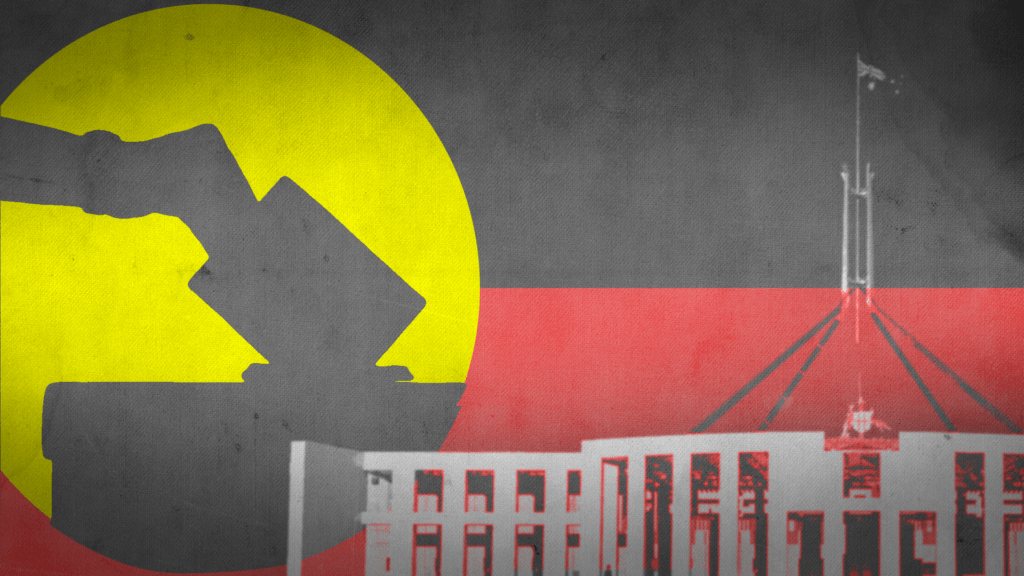

Australians have been inundated with polling updates ahead of the Indigenous Voice referendum, but it’s not clear whether that’s been particularly helpful. : AEC images, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0 DEED (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/)

Australians have been inundated with polling updates ahead of the Indigenous Voice referendum, but it’s not clear whether that’s been particularly helpful. : AEC images, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0 DEED (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/)

Polling is back in vogue during the Voice referendum debate and those results — rather than the substance of the debate — could influence the way some vote.

Australia’s view on the Indigenous Voice referendum has been keenly centred on political polling. News outlets regularly fixate on poll results, which they treat as crystal balls forecasting the referendum outcome, months in advance.

Political polling in the debate reflects a self-fulfilling prophecy, where the numbers become the story rather than being used to help tell it.

Polling is centre stage in Australia now, but only four years ago it was on the brink: the country’s second-largest media company, Nine Entertainment, declared it would stop publishing weekly polls from Ipsos after the 2019 federal election result defied pollsters’ predictions.

But polling has surged back to prominence amid a narrative of declining support for the Yes campaign, which extends with each fortnightly poll update.

Different outlets approach the same poll data with their own twists: The Guardian reports each new Essential poll as a “slim majority” for the No vote, while Sky News Australia coverage of Roy Morgan results says support for a Yes vote “plunges“, “freefalls“, and “plummets“.

This renewed attention on political polls is not surprising, given their potency within the political and media ecosystem.

Polls — especially those conducted regularly — provoke reaction and are big business, with complex, often obscured long-term relationships between news outlets and pollsters.

Backlash to polls in Australia came after the 2019 federal election, in which federal Opposition leader Bill Shorten lost an “unlosable election” after spending two years ahead in polling. The disparity between polling and the outcome led some commentators to describe the failure to predict Shorten’s loss as “worse than the Trump polling fail” in 2016.

Criticism centred on the polls’ accuracy, but also on the strong expectation for a result that did not eventuate that these polls helped to create.

In 2019, statisticians and scientists, notably including Nobel Laureate physicist Brian Schmidt, called for major reviews of pollsters’ methodologies, warning of “undue, or undeserved, influence” on vote results.

A group of pollsters — YouGov, Essential, and uComms — responded by forming the Australian Polling Council to reassure journalists and the public of the quality of their data and improve accuracy in reporting.

But worries about poll accuracy in reporting distract from more critical issues — like how polls are used to further existing political narratives, and the impact of reporting poll results in the first place.

Schmidt’s commentary focussed on the likelihood of pollsters adjusting— probably unintentionally — poll results to match each other.

But this concern should extend beyond just those conducting the polls. The media too readily overlooked the effects of constantly polling and publishing poll results to the public.

The most effective use case for polling data is often internally, providing political campaigns with regular profiles of the voters they are fighting to win.

This doesn’t mean they should be published more widely: if the aim of the media is to inform the public, the question must be asked what benefit there is from knowing how others will vote.

Aspects of the Voice referendum might generate increased attention to political polls — and generate greater susceptibility to simple narratives.

The increased focus on polling could be due to the heightened stakes in any referendum, given its binary nature. A referendum takes a weighty issue and funnels it into two opposite responses.

But, unlike an election, referenda require a majority of states to approve the constitutional change, as well as a national majority.

Reporting that highlights the fact that the national figures do not reflect the full picture, and that there are still a substantial number of uncertain voters, might be missed entirely.

The ABC and the Guardian maintain multi-poll trackers to try to produce a more powerful picture of campaign performance beyond the limits of individual polls. But in doing that, they remove undecided respondents, “to give a forced yes/no response”.

This is the poll reporting trade-off: a clearer image, but one constructed by removing nuance.

This can have an unchecked effect on how we perceive the campaign. Beyond technical issues with getting polling right, it’s hard to regulate against people using polls out of context.

Some Australian voters say they don’t understand the constitutional changes or feel the involvement of non-Indigenous Australians in this issue is fundamentally unethical. In any case, there could be more demand from people seeking cues on how to vote.

People might feel they don’t know enough about the referendum question. Market research firm Essential estimates that only 49 percent of Australians feel well-informed, less than a week from the vote.

However, there is a clear desire from the campaigns to be aligned with the way Indigenous people intend to vote.

The Yes campaign frequently references 80 percent Indigenous support, a figure which has been contesteddrawn some contestation.

Fact-checking from August concluded that, while the figure could be outdated and more uncertain than reported, actual support was still most likely above 50 percent.

Most crucially, experts agreed there was no equivalent evidence for No vote support. To counter his claim, the No campaign’s pamphlet reads “many Indigenous Australians do not support this”. The No campaign has centred prominent dissenting Indigenous voices, though in at least one case has been accused of misrepresentation.

Documents like the Uluru Statement from the Heart are central to the agenda. But near the end of the referendum campaign, nearly a third of more than 1000 voters surveyed claim to have never heard of it.

Using poll data to glean popular opinion is a convenient, but problematic shortcut for voters as they make their decision.

Such coverage creates a feedback loop. Simplified snapshots offer a quick alternative, disconnected from deeper engagement with the issue.

This would mean voters are using poll results as a summary of the debate, with their vote guided by duelling polling worms.

Just like the herding effects of pollsters unconsciously adjusting their results to mimic each other, the constant reporting of polls can have a self-fulfilling effect.

The extent of this effect on individual beliefs is hard to measure, but much clearer in terms of how repetitive polling and a fixated media ecology can result in exaggerated narratives and distort perceptions.

Researchers at the Queensland University of Technology’s Digital Media Research Centre investigated the drivers behind polarisation. There was a particular focus on the importance — and difficulty — of distinguishing perceptions of polarisation from actual differences in voting intention, and the role of the media in both.

Researchers asked Essential Media to conduct a brief survey on perceptions of division during the referendum debate.

Older people were far more concerned about the effects of social media amplification, power-hungry politicking and media bias than other respondents, but all were concerned about the effects of businesses prioritising profits in driving up the cost of living and worsening social divides.

These results could reflect the effects of destructive feedback loops from the kind of narratives that political polling coverage helps to perpetuate.

The 1,151 participants were also asked their voting intent for the Voice referendum.

Those who saw Australia as a divided country were more likely to vote No (59 percent) — while those who saw Australia as united were more likely to vote Yes (58 percent).

The overall response was 27 percent “quite or very united” to 42 percent “quite or very divided”, with 31 percent neither.

This has implications for the focus of the No campaign, which has centred on claims the Voice will be divisive for Australia.

But perceptions of division and Voice voting intent do not completely overlap. This survey data raises more questions about the motivations and existing tensions mobilised during the referendum campaign.

While solutions like the Australian Polling Council regulations can improve the accuracy of poll reporting, poll reporting will still never tell the full picture.

Samantha Vilkins is a postdoctoral research associate at the Queensland University of Technology’s Digital Media Research Centre.

Samantha Vilkins receives funding from the Australian Research Council through Laureate Fellowship FL210100051 Dynamics of Partisanship and Polarisation in Online Public Debate.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.