Agribusiness corporations have been on the rise in India since the 1970s. Unless there is a change in government policy smaller farms face a bleak future.

Indian conglomerates like Reliance Fresh now operate in the fresh food supply chain. : Kalyan/Flickr

Indian conglomerates like Reliance Fresh now operate in the fresh food supply chain. : Kalyan/Flickr

Agribusiness corporations have been on the rise in India since the 1970s. Unless there is a change in government policy smaller farms face a bleak future.

A qualitative change took place in Indian agriculture in the 1970s: the government said not only that the country had achieved domestic food self-sufficiency but also that it had surplus food for export. This sparked the rise of agribusiness corporations, whose dominance now threatens India’s traditional variety of trading networks, food markets and small family farms.

The food surplus was illusory: it existed because the extremely poor in urban and rural areas did not have the purchasing power to buy enough food to meet their needs. Nevertheless, the link between India’s food markets and the international marketing of food emerged from this ‘surplus’.

The ‘surplus’ gave birth to a new class of large-scale traders who networked with global agri-business corporations to export food. The food export sector has grown so substantially that India has become the world’s leading rice exporter, with exports valued at US$7.1 billion in 2019–20.

The neoliberal policy paradigm introduced in India in July 1991 was instrumental in boosting food export businesses. It also contributed to accelerating the diversification of large corporate houses into procuring, transporting, storing, processing and distributing food. The three farm laws introduced by the government in June 2020 represented the interests of the global agribusiness corporations aligned with Indian corporations that had diversified into agribusiness.

The most dramatic of the three laws, The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act 2020, removed all limits on the storage of food that had been introduced in the 1955 version of the Act. The 1955 Act made hoarding of ‘essential’ commodities (cereals and sugar) legally punishable, but the amended Act invited large-scale speculative hoarding of food. The farmers’ movement, which arose out of farmers’ fear that their livelihoods and ecological sustainability would be taken over by large agribusiness corporations, forced the government to repeal the three laws in November 2021.

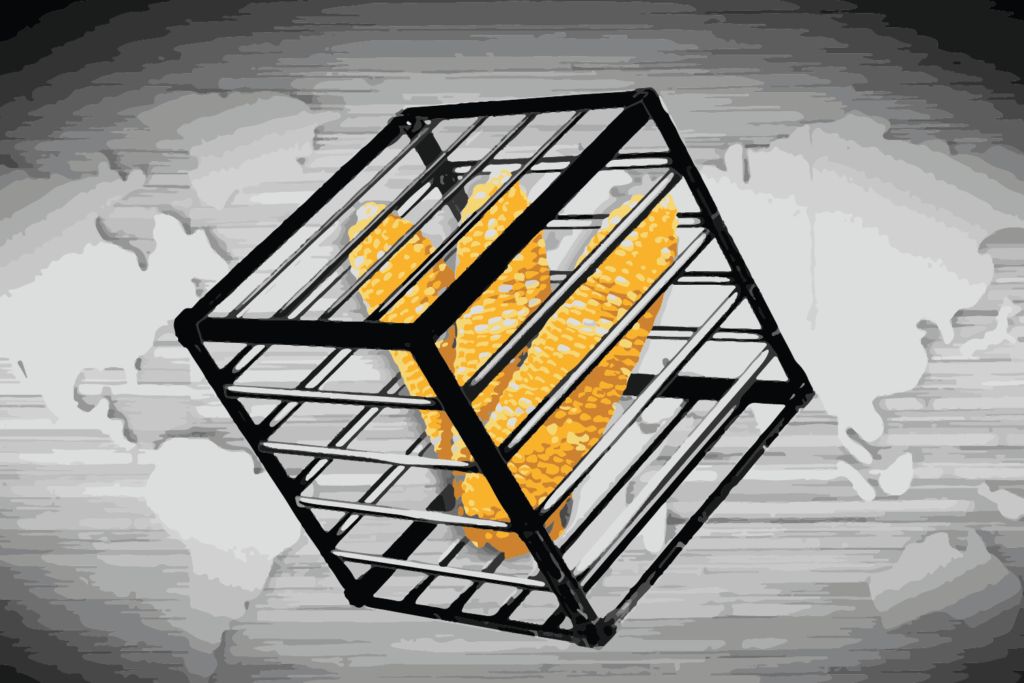

Though the farmers’ movement succeeded, at least temporarily, in resisting the monopolisation of the food trade by agribusiness interests, the trend towards monopoly control of agrifood chains that has been going on for a few decades has not been reversed.

The infrastructure that has been built over the years for this monopoly control remains intact and is expanding. Since the mid-2000s, subsidiaries of major Indian industrial conglomerates have entered the fresh-food supply chain: Reliance Fresh, Adani Agri Fresh, Bharti’s Field Fresh and others.

In parallel, Adani Agri Logistics has built and operated grain silos for the central government’s Food Corporation of India (FCI) in an ongoing public–private partnership. The latter activity has accelerated since 2017, with new private railway lines, automated grain-processing plants and other infrastructure built around these outsourced FCI silos in Punjab and Haryana (the two major food-producing states) as part of a wider process of capturing logistical chains.

The public sector, at central and state levels, has been subsidising corporate expansion. The state has facilitated the creation of a private security force by the Adani Group to protect its infrastructure of private railway lines, silos and grain-processing plants. Nearly 900 Adani-controlled silos have been set up all over India to facilitate grain storage and interstate as well as international food trade.

A new threat, potentially even greater than monopolisation of grain storage, to small-scale and family farming is now emerging from high-tech agribusiness corporations that aim to digitise all agricultural activities to create a business in big data. Potential for data mining is huge.

Agricultural research data in India is currently split across multiple state and central institutions. Proposed apps can get real-time information on soil, weather, pests and other factors directly from farmers, who will likely be required to provide data in order to use platforms. Futures trading also requires large datasets of price information. There are moves to create a nationwide AgriStack database to enable rapid data modelling rather than spending disproportionate time and effort on data collection.

One of the key purposes of digitising data will be to facilitate automation through the introduction of drones, sensors and robots that will displace human labour. The food sovereignty of small and family farmers will be wiped out by such large, high-tech farms. Agribusiness corporations producing food through such farms will contribute further to the consolidation of food storage.

The growing evidence of collaboration of domestic agribusinesses such as Adani and Ambani with international agribusiness entities such as Cargill is an indication of the growing scale of consolidated monopoly power in agrifood chains.

The enormous power of such large corporations increases income vulnerability for small farmers and food insecurity for rural and urban consumers. To challenge this power, the organisations of Indian farmers and rural workers will have to build even stronger solidarity networks with urban workers and consumers than they did during their successful struggle in 2021.

Pritam Singh is Professor Emeritus at Oxford Brookes Business School, Oxford, UK

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: Prof. Pritam Singh