While the hype around deep sea mining is real, there may be unintended consequences that will come with it.

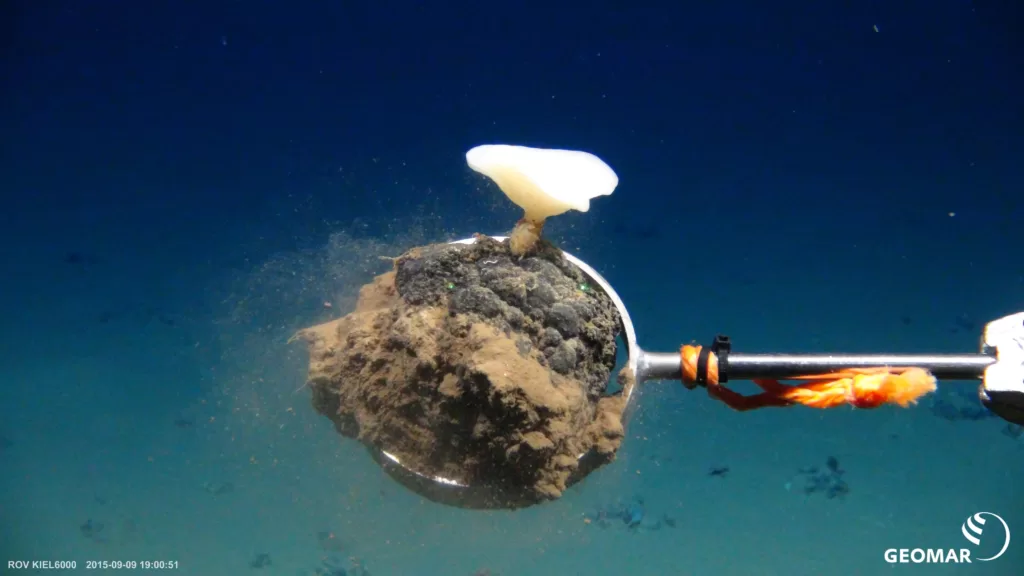

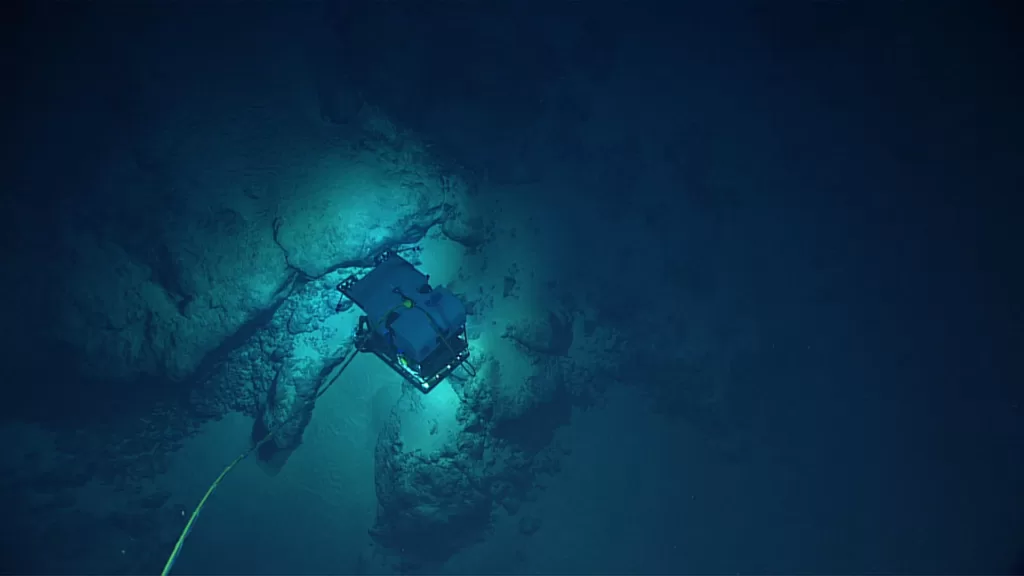

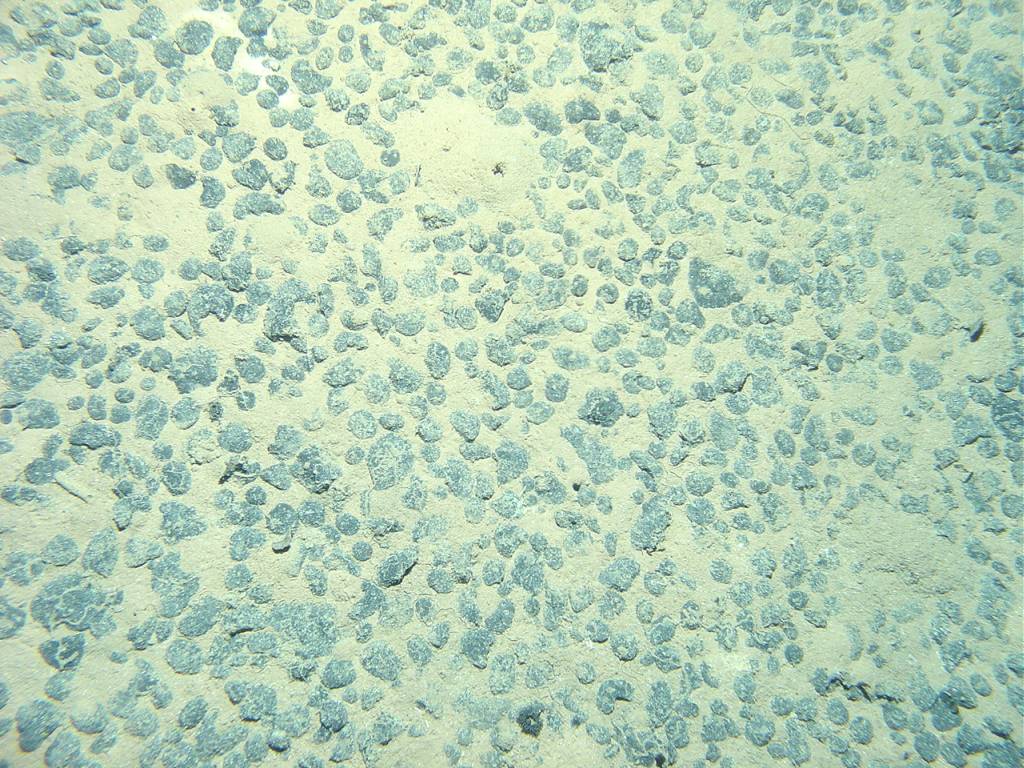

Polymetallic nodules are set to be mined in the deep sea. : Abramax, Wikimedia Commons CC

Polymetallic nodules are set to be mined in the deep sea. : Abramax, Wikimedia Commons CC

While the hype around deep sea mining is real, there may be unintended consequences that will come with it.

An often overlooked element of our global energy transition is that all low-carbon energy technologies need a range of minerals and metals that can only be sourced through mining.

Some of these — cobalt, copper, manganese and nickel — are found in large quantities deep in international waters in the Pacific Ocean.

Commercial deep sea mining is likely to start there soon as the International Seabed Authority — the governing body under the UN Convention Law of the Sea — will finalise deep sea mining regulations in July.

We debunk some deep sea mining myths to better anticipate what is coming next.

Myth 1: There are not enough resources on land to power the energy transition

A recent study found a full transition to electric vehicles by 2050 could increase the demand for lithium by 75 times, nickel by 54 times, cobalt by 27 times and manganese by 28 times.

However, the availability of these resources on land does not seem to be an issue as several studies found the demands do not exceed geological reserves.

And doomsday predictions of insufficient resources to meet the minerals needed for our energy transition have so far been debunked.

If availability is not an issue, access could be the real issue.

Mining and mineral processing are concentrated in a few countries and accessing large quantities of minerals to meet net-zero targets on time will be challenging.

Although it seems decision makers are progressing to mitigate this supply risk.

Manufacturers are minimising their exposure to risk by finding substitutes to some of the most critical minerals.

Cobalt is being replaced in new generations of batteries.

This year, Tesla announced it will be moving away from rare earth elements.

Governments are also acting to minimise risk. The US and UK governments and the EU are making strategic moves to on-shore production, or “ally-shore” and diversify supply.

Overall, while there is a risk of supply disruption, it appears both governments and manufacturers are making strong moves to mitigate it.

Myth 2: Deep sea mining will improve energy security

Advocates for deep sea mining claim it can contribute to energy security by diversifying supply and providing much needed metals at a lower cost.

Polymetallic nodules which are set to be mined in the deep sea only contain high concentrations of manganese, nickel, cobalt and copper, supplying only four of more than 30 minerals identified as critical or strategic.

Manganese is the most abundant metal in the deep sea. But manganese is also an abundant resource on land.

Advocates have also claimed deep sea mining would reduce reliance on countries like China that currently have too strong an influence on supply, or a near monopoly in some cases.

This ignores the fact China is already a leader in deep sea mining exploration, meaning a shift to deep sea mining would not necessarily decrease Chinese influence on supply.

Myth 3: Deep sea mining will be less harmful than conventional mining

Deep sea mining has been claimed to be less harmful than conventional mining, with human rights abuse in cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo and deforestation from nickel mining in Indonesia cited as two examples of how exploitative the mining industry can be.

But much of the risks from deep sea mining are still unknown, unlike conventional land-based mining, which has benefited from decades of research into its social and environmental impacts and how they can be mitigated.

There is another issue that has been overlooked so far: the negative effects deep sea mining would have on those who rely on the terrestrial mining sector.

Experts interviewed by the World Economic Forum predict deep sea mining could result in lower revenues from land-based mines as they become less commercially viable — particularly cobalt, copper, manganese and nickel operations.

So far we know these effects are highly uncertain and unpredictable. But if supply from the deep sea were to lower commodity prices, this would directly translate into lower mining revenues and benefit sharing.

There are many developing countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Brazil and the Philippines where mining contributes heavily to economic development by creating jobs, business development, increasing tax revenues and better infrastructure.

In times of economic downturns, the industry will likely seek to maintain profit levels and minimise financial risk. This can translate into mine abandonment and periods of care and maintenance.

Abandoned mines compromise site rehabilitation, transferring environmental legacies to the state and leaving local communities in limbo. During care and maintenance periods, social and environmental programs are also frequently cut.

A healthy and financially stable mining industry can generate value and mitigate negative impacts of its activities.

Moving forward

The mining sector needs to prepare for the indirect effects a rise in deep sea mining may have on terrestrial operations.

To minimise the risks, it can assess its exposure by assessing the vulnerability of its cobalt, manganese, copper, and nickel assets.

Industry and government should also consider the vulnerability of the communities in which these assets are located.

Investing in innovation will help them to stay competitive. This includes social and environmental innovation — which is often overlooked. Miners could invest in recycling, to profit from primary and secondary supply of critical minerals.

There are strong opportunities to source cobalt from mining waste instead of the deep sea.

Importantly, the industry will need to make careful decisions about where to invest in new mining projects.

Understanding the land and communities earmarked for projects is crucial for improved environmental and social outcomes.

Eleonore Lebre is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, Sustainable Minerals Institute, The University of Queensland. She is a 2022 recipient of the Discovery Early-Career Researcher Award from the Australian Research Council.

The research was funded by the Australian Research Council.

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that European countries have so far refused to go into the deep sea mining space. This has been corrected.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “MINING THE DEEP” sent at: 03/07/2023 07:32.

This is a corrected repeat.