Indigenous cultural relationships to the seabed have already been taken into account in three successful court proceedings in South Africa.

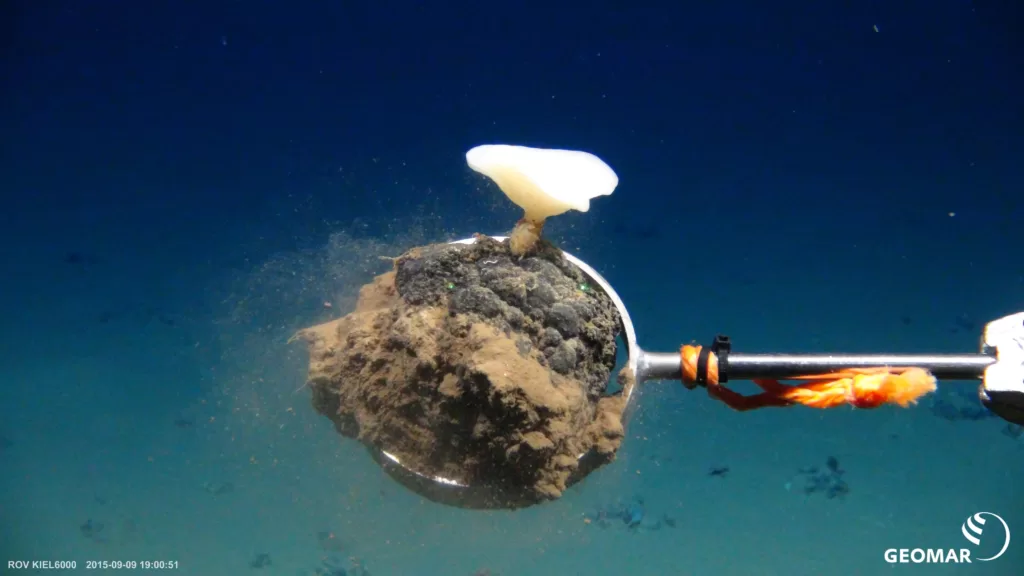

Still from the animation Indlela Yokuphila. : Marc Moyinhan and Dylan McGarry CC BY 4.0

Still from the animation Indlela Yokuphila. : Marc Moyinhan and Dylan McGarry CC BY 4.0

Indigenous cultural relationships to the seabed have already been taken into account in three successful court proceedings in South Africa.

Pacific island nations worried about the impacts of deep sea mining could consider new alliances with communities across the world where Indigenous knowledge is being used to protect the seabed.

In South Africa, many Indigenous cultures revere the seabed as the realm where ancestors dwell.

Research across the social and marine sciences, arts and Indigenous knowledge in South Africa has revealed that Zulu traditional ancestral beliefs on the soul’s journey has parallels with the scientific understanding of the role of the ocean in the global water cycle.

This research, and the artwork that surfaced it, have led to unprecedented judicial developments in South Africa about the urgent need to protect the seabed, including through meaningful participatory processes for decision-making that protect cultural rights.

These developments are important also for the deep seabed outside the jurisdiction of any nation and hence under the mandate of the International Seabed Authority.

They support growing calls for the integration of Indigenous knowledge and enhanced public participation in its proceedings.

Indlela Yokuphila: The Soul’s Journey is a five-minute animated film that uncovers the parallels between Zulu spirituality and science’s understanding of the ocean’s role in the global water cycle.

It presents the soul’s journey after death, from transforming into a young ancestor travelling through underground streams and river systems, all the way to the deep sea where ancient wisdoms reside.

The ancestor dwells on the seabed for a long time, until their soul ascends to the surface, is carried by a cloud and rained down in a village, where their next mother drinks the rainwater and holds inside the ocean of her belly the ancestor that will grow to be born again.

This understanding responds to a key research finding at different levels of ocean governance.

The largest oversight in ocean governance is including spiritual and cultural heritages in decision-making and marine spatial planning, which leads to unsustainable and exclusionary decisions that may violate human rights.

Indlela Yokuphila was instrumental in three successful court proceedings in South Africa in 2022-2023, brought by Indigenous fisher leaders and ocean defenders against oil and gas companies and the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy for permitting seismic surveys for offshore oil exploration.

These judgments marked the first time an animation has been used as evidence in a South African court, serving as a proxy for intangible cultural heritage related to the ocean.

Judge Bloem, in Part A of the case, related to respect for cultural and spiritual relationships with the ocean, said:

“I accept that the customary practices and spiritual relationship that the applicant communities have with the sea may be foreign to some and therefore difficult to comprehend.

“How ancestors can reside in the sea and how they can be disturbed may be asked. It is not the duty of this court to seek answers to those questions. We must accept that those practices and beliefs exist …

“In terms of the Constitution, those practices and beliefs must be respected and where conduct offends those practices and beliefs and impacts negatively on the environment, the court has a duty to step in and protect those who are offended and the environment.”

This judicial recognition of the sacred nature of this relationship as human right to culture led the court to heighten the protection of the participatory rights of these communities in decision-making processes on proposed uses of the seabed which negatively affect marine life and the livelihoods of fishing communities.

These judicial decisions can be interpreted as a recognition of the crucial role of Indigenous and other coastal communities as environmental human rights defenders that support everyone’s human right to a healthy environment.

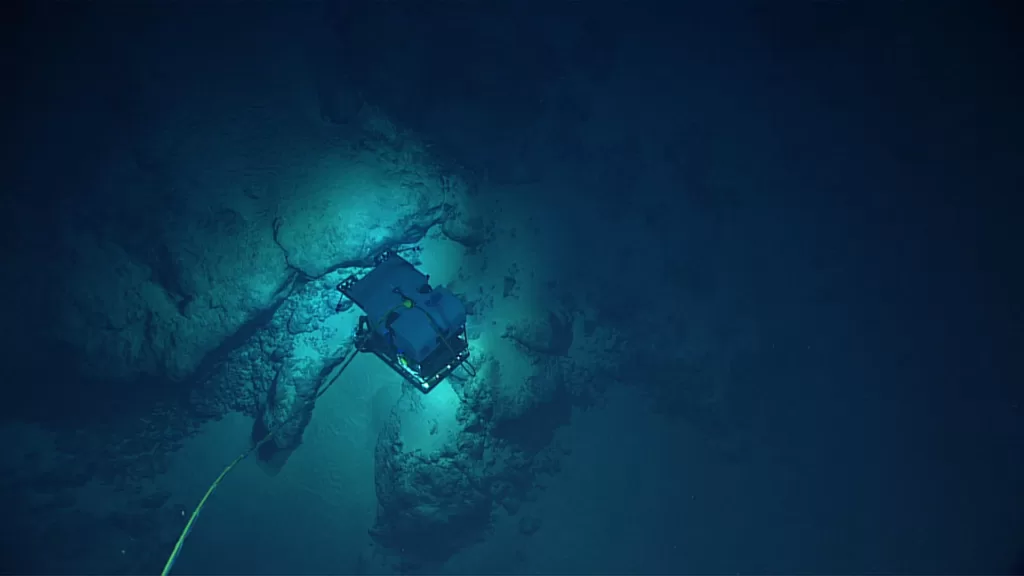

There is no evidence that Indigenous cultural attachments to the seabed do not extend to the Area — the portion of the deep seabed under the Seabed Authority’s aegis.

Environmental concerns related to the Area should be understood in the light of ecological connectivity: due to oceanographic processes and the movement of migratory species, coastal areas can also be affected by decisions on activities in the Area.

What Indlela Yokuphila indicates for the Authority is that there is available, relevant Indigenous knowledge on the protection of the marine environment in the Area.

This Indigenous knowledge parallels relevant scientific knowledge on the role of the ocean in the global water cycle, which needs to be considered in biodiversity conservation and sustainable use in areas beyond national jurisdiction according to the recent agreement on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, as well as activities that fall outside the purview of the agreement like deep sea mining.

It also provides evidence of relevant cultural heritage and underlying cultural rights that could be taken into account through participation in international decision-making that could have an impact on these rights, including heightened protection for environmental human rights defenders.

Cultural heritage is be an important consideration in the decisions adopted internationally, so they can genuinely contribute to sustainable development, according to international human rights standards.

Accordingly, member states of the Authority can take precautionary measures to prevent possible impacts from deep sea mining that may result in the reduced availability, accessibility or acceptability of marine spaces and marine resources (in the Area or in other marine areas ecologically connected to the Area).

These marine spaces and resources are essential for Indigenous peoples’ culture on which their identity, wellbeing and development depend.

Mpume Mthombeni is a co-director of Empatheatre and a research associate at the Environmental Learning Research Centre at Rhodes University, South Africa. She is an award-winning performer and theatre-maker who hails from Umlazi, Durban. Her work with Empatheatre focuses on merging research and performance and she considers the theatre-maker’s role in contemporary South Africa to be that of healer and shaman.

Dr Dylan McGarry is a senior researcher at the Environmental Learning Research Centre at Rhodes University, South Africa, a member of the One Ocean Hub and co-founder of Empatheatre. They are a filmmaker, theatre practitioner, artist and educational sociologist who works in the areas of social-ecological justice, transformative social learning, activism, Empatheatre and earth jurisprudence.

Elisa Morgera is a professor of global environmental law at the University of Strathclyde, UK, and the Director of the One Ocean Hub. She specialises in international, European and comparative environmental law, with a particular focus on the interaction between biodiversity law and human rights (particularly those of Indigenous peoples and local communities), equity and sustainability in natural resource development, oceans governance, and corporate accountability.

This article draws from research undertaken by the authors under the One Ocean Hub, which is a collaborative research programme for sustainable development funded by UK Research and Innovation through the Global Challenges Research Fund.

The research is based on a chapter written in McGarry, D (2023). ‘When ancestors are included in ocean decision and meaning-making.’ Chapter 2 in T Shefer, V Bozalek and N Romano (editors) Hydrofeminist Thinking with Oceans: Political and pedagogical possibilities. Routledge, in press.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.