If spacefaring nations can set aside geopolitics, the hope and cooperation that characterised the dawn of the space age will come to the fore once again.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin are close allies, both on Earth and in matters beyond. Picture: The Presidential Press and Information Office, Wikimedia Commons : The Presidential Press and Information Office, Wikimedia Commons

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin are close allies, both on Earth and in matters beyond. Picture: The Presidential Press and Information Office, Wikimedia Commons : The Presidential Press and Information Office, Wikimedia Commons

If spacefaring nations can set aside geopolitics, the hope and cooperation that characterised the dawn of the space age will come to the fore once again.

With the launch of Sputnik in 1957 and Yuri Gagarin’s space flight in 1961, Russia’s spacefaring marked the dawn of a new age. The era saw treaties that expressed aspirations for international cooperation and the betterment of humankind.

In recent decades, though, space technology has often been treated by nations as a tool for gaining national power and status.

Parties to the 1967 UN Outer Space Treaty recognised “the common interest of all mankind in the progress of the exploration and use of outer space for peaceful purposes” and declared their belief that “the exploration and use of outer space should be carried on for the benefit of all peoples irrespective of the degree of their economic or scientific development”.

Space technology, including manned technology, has the potential to greatly enhance the development of science and technology in general. In turn, this advancement would not only create wealth and jobs but also contribute to the development of intelligent technology, significantly enhancing human society and our well-being.

In 2011 the UN General Assembly declared that it was “deeply convinced of the common interest of mankind in promoting and expanding the exploration and use of outer space, as the province of all mankind, for peaceful purposes and in continuing efforts to extend to all States the benefits derived therefrom”.

In 2015 the UN General Assembly adopted the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (UN 2030 Agenda), which put forward 17 Sustainable Development Goals. These address the three dimensions of society, economy and environment, so the world can move along a sustainable development path.

Based on the contribution of space science and technology to human development, manned space-flight technology can make a great contribution to the UN 2030 Agenda.

At the first UN Conference on the Exploration and Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNISPACE+50), held in Vienna in June 2018 the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS) presented the Space 2030 Agenda.

It articulated a comprehensive, inclusive and strategically oriented vision for strengthening international cooperation in space exploration. In the Space 2030 Agenda space is seen as a major driver of, and contributor to, the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

According to realist theory, a nation’s power and status include technology and military power. Space technology is a dual-use technology and a symbol of a country’s overall technological and military power. Great powers invest in the space sector in order to gain power and status. Manned flight was the result of the United States–Soviet Union space race during the Cold War. The US and the Soviet Union competed fiercely to land a crewed vessel on the Moon, and ultimately the US won the race.

After the 2010s, the space powers began a new race to the Moon. They sought lunar sovereignty under the pretext of mining the Moon for minerals (or at least jurisdiction over the mining areas). Although manned lunar landings and exploitation of lunar resources are beneficial to human society, participating countries (especially the US) were really aiming to increase their own power and status.

In line with the above, some countries use space technology as an arm of diplomacy and as a tool to advance national interests – for example, by offering or denying space technology to other countries. During the Cold War era, the US provided space technology to its allies, friends and partners to enhance and consolidate US leadership in the West; conversely, the Soviet Union denied space technology to its partners to keep them under its control. As a result, the US and the West won the Cold War–era space competition.

In the post–Cold War era, the US continues to cooperate with its allies and partners in space, hoping to establish a unified front in the development of new space rules and thereby establish a space order and space landscape in its favour.

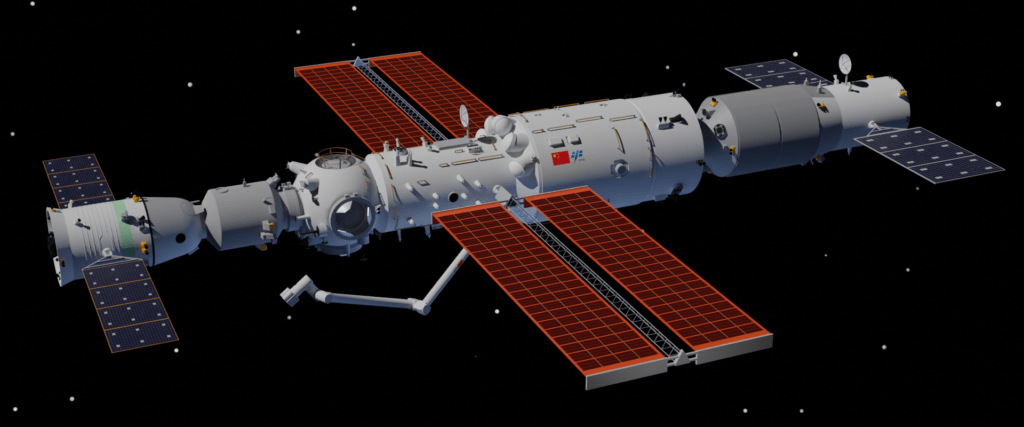

Russia and China, in the meantime, have intensified their cooperation. The two countries coordinate closely and jointly propose initiatives such as the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space Treaty and the No First Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, which aim to prevent the weaponisation and battlefielding of space.

In space technology, the two countries work closely together to form a relatively stable space triangle consisting of China, Russia and the US. China and Russia have cooperated in human space flight and a joint exploration of Mars and the Moon. They are also working together to develop navigation satellites, jointly constructing international lunar research stations and exchanging rocket-engine technologies.

There is also a strong relationship in the field of space military technology. Russia provides China with early-warning technology, and the two countries conduct computer-simulated anti-missile drills together.

Importantly, China and Russia supply public goods for space, aimed at preventing the emergence of a space ‘Kindleberger trap’ – an undesirable situation in which rising powers fail to provide the international public goods that declining established powers are supposed to provide during a period of transitioning power. The term is named after US policy architect Charles Kindleberger, who saw this set of circumstances as the catalyst for much of the global instability of the 1930s.

At present, cross-border cooperation in space technology is terminated or cancelled during times of crisis or conflict. At the beginning of the Russia–Ukraine conflict, the West and Russia mutually cancelled their space cooperation. The only redeeming factor is that the West and Russia continue to cooperate on the International Space Station.

Space technology now carries too great a geopolitical load, depriving it of its supposed mission of promoting international peace and the common welfare of humanity. For the sake of the continuation of human civilization and its advancement to a more distant planet, it is time to return space to peaceful use. The words of the Outer Space Treaty must be on everyone’s mind.

Perhaps the first and last American astronauts to land on the Moon said it best. Neil Armstrong declared that landing on the Moon was “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”. Gene Cernan, the last astronaut to walk on the Moon, got back into the lunar module and promised: “We shall return in peace and hope for all mankind”.

Manned space technology can make a tangible contribution to the achievement of the UN 2030 Agenda and can deliver on COPUOS’ commitment to the Space 2030 Agenda.

In future manned space flights, all spacefaring powers could benefit from abandoning geopolitical thinking and working together to use space technology to combat the risks and threats humanity faces.

Qisong He is a professor at the East China University of Political Science and Law, Shanghai, China. Prof. He declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.