While there is some correlation, it is wrong to say supply chain kinks are a primary cause of inflation.

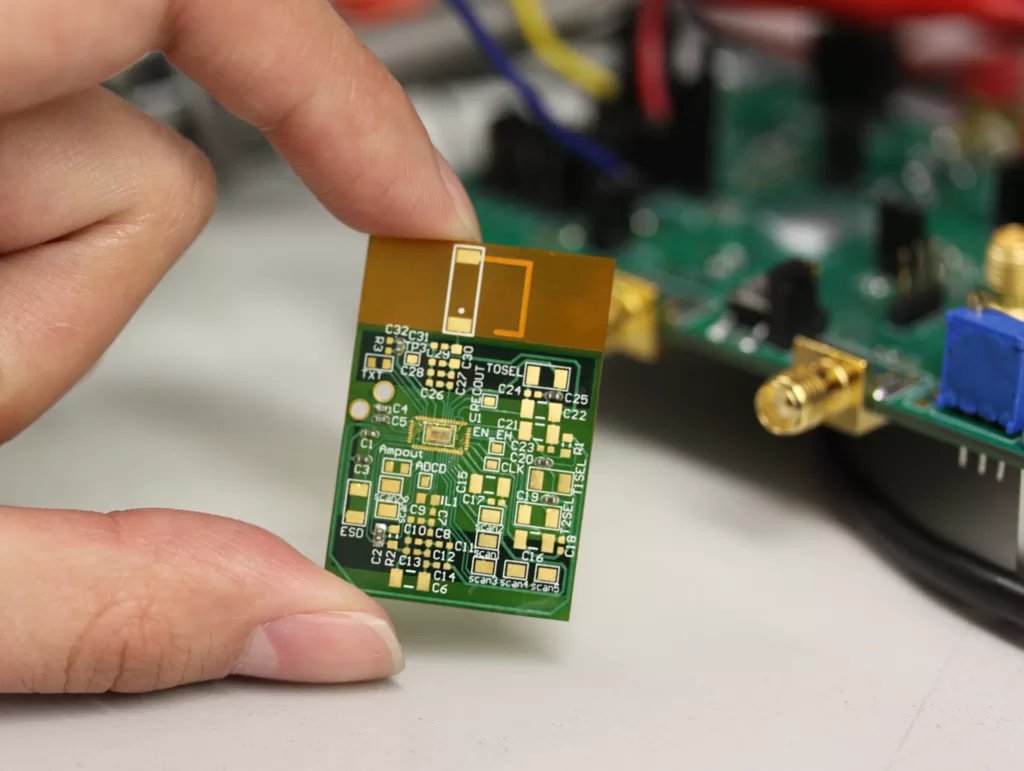

The recent global chip shortage is a good example of how supply chain disruptions often sort themselves out. : ‘Body monitoring chip’ by Larry Pribyl is available at https://bit.ly/40b0tSi CC BY-SA 2.0

The recent global chip shortage is a good example of how supply chain disruptions often sort themselves out. : ‘Body monitoring chip’ by Larry Pribyl is available at https://bit.ly/40b0tSi CC BY-SA 2.0

While there is some correlation, it is wrong to say supply chain kinks are a primary cause of inflation.

There is a common misconception that when supply chains are disrupted, entities along the supply chain shore up more resources to overcome the supply and demand imbalance.

With the excess cost ultimately passed onto consumers, this supposedly causes an inflationary ripple effect across the economy. A further myth is that this inflation then boomerangs onto the supply chain, leading to a vicious cycle.

When the global supply chain was disrupted during COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020, one ubiquitous component that had vast implications on the supply chain was the computer chip.

The chip, also known as a semiconductor, is a fundamental component in all electronic devices such as computers, mobile phones, lightbulbs, home appliances and credit cards.

At the onset of the pandemic, chip production was halted and shipping slowed down due to various factors, including a predicted drop in demand.

However, with a large proportion of the population working and studying from home and the rapid digitalisation of businesses, the demand for electronic devices actually increased significantly.

This soon led to a global chip shortage affecting most manufactured goods’ supply chains worldwide. On the supply side, the chip shortage caused the automotive industry to reduce vehicle production and delay delivery to consumers.

On the demand side, when the world emerged from COVID-19 and business activities resumed, consumer demand for vehicles exceeded supply, resulting in an increase in price.

What compounds the supply-demand imbalance is the fear of further shortages when entities along the supply chain stockpile inventory in anticipation of even higher demand.

With one firm — the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation — dominating more than half of global chip manufacturing, including almost 90 percent of advanced made-to-order chips essential for emerging technologies, the acute shortage worsened.

But inflation began to slow down even when the trajectory seemed to be heading towards a vicious cycle of supply chain disruption and inflation impeding the supply chain even further.

External shocks are usually temporary, and supply and demand will eventually balance out. Inflation can solve itself. Consumers are not always willing to pay more for goods they do not need. As prices of consumer goods surge, consumers cut back on their purchases and demand recedes.

Previous production expansions and equipment tooling up to resolve the shortage can turn into inventory surplus and excess capacity. Given the oversupply, manufacturers begin to reduce capital spending and hiring. Hence, amid weaker demand, prices will fall.

The semiconductor industry, primarily driven by market factors, often undergoes cyclical peaks and troughs. Inflation and supply-side disruptions associated with shortages are usually short-term. Therefore, the inflationary myth.

Research has shown that improvement in operations and supply chain efficiencies, shortened production times and investment in new fabrication plants and technologies mitigate disruptions over time.

Except for COVID-19 as an anomaly, while there is a correlation between supply chain disruption and inflation, the former is not the primary contributor.

The impact of supply chain disruption on core consumer prices is, in fact, not significant. The reality of inflation goes beyond its effect on consumers’ income and household purchasing power.

One thing businesses need to be aware of is the ‘bullwhip effect’ in resolving shortages. The bullwhip effect is a supply chain phenomenon often used to explain inaccurate information in assessing demand.

Slight order variations progressively become amplified upstream from the retailer to the manufacturer. The bullwhip effect often leads to inventory build-up and ultimately price deflation.

Care needs to be taken so distortion of information along the supply chain does not lead to excessive fluctuations.

Lessons from past natural disasters, such as the 2011 Thailand flood crisis, can be instructive. Computer prices skyrocketed when flood waters inundated hard disk drive manufacturing hubs in Southeast Asia.

Given the concentration of production in a single location, supply chain disruption in one region had sizable ramifications globally. But market forces tend to solve bottlenecks.

As the hard disk drive fabrication plants resumed operations, so did the inventory level, and eventually, prices came down. In addition, solid-state drives became preferred over hard drives in the long run after the clamour for a viable alternative to overcome the shortage.

The chip debacle highlights the susceptibility of the global supply chain to external shocks and hence the need for risk management to ensure supply chain resilience.

Although government policies can support the supply chain in mitigating inflation, emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, the Internet of Things, robotic process automation, cloud computing and big data analytics also have the potential to improve supply chain visibility and agility in handling unusual circumstances.

Their increasing use in smart factories is expected to drive future demand for advanced chips. Given their importance to almost all major industries, this means chip demand should increase in the long term but the contention that this is a primary cause for inflation needs to be backed up.

Andrei Kwok is Senior Lecturer and Director of Graduate Coursework Studies, Department of Management, School of Business, Monash University Malaysia. He declares no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.