As Charles is set to be crowned it's unclear if he's inherited the love felt for his mother or whether it's time for Australian republicans to stage a new push.

The death of Queen Elizabeth II in September 2022 led to an outpouring of grief across the world. : Doyle of London via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

The death of Queen Elizabeth II in September 2022 led to an outpouring of grief across the world. : Doyle of London via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

As Charles is set to be crowned it’s unclear if he’s inherited the love felt for his mother or whether it’s time for Australian republicans to stage a new push.

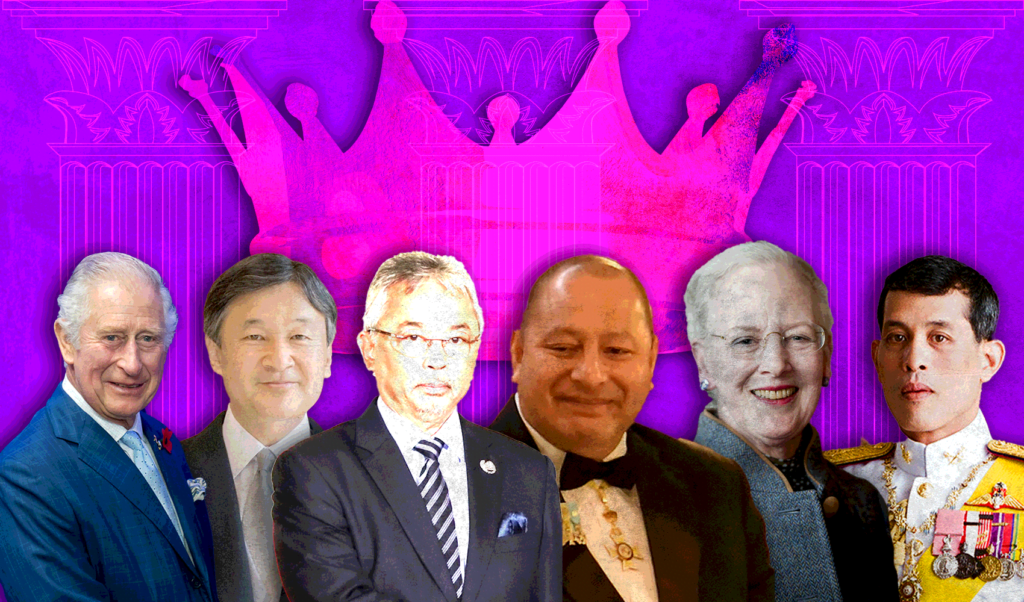

A transition to a new sovereign inevitably prompts questions about whether the monarchy remains fit for purpose and whether the time for republicanism has finally arrived.

However, it’s unlikely Australians will be sending King Charles III packing anytime soon.

The Aussie sense of fair play means he should be given a chance — he has waited long enough for the job. And the new king has long had an affection for Australia, where he lived and worked as a young man.

Australians also felt a deep respect and affection for Charles’s mother, Elizabeth, when she was queen. Even Australia’s republican leaders, such as former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, recognised that affection made it harder to seek constitutional reform during her lifetime.

In 2015, researchers looked at how the crown functioned in Australian society compared to the United Kingdom and the post-colonial Commonwealth realms of Canada and New Zealand, and predicted the likelihood of republican reform in any of these countries.

Since then, there’s been plenty of royal detritus under the bridge: Prince Harry’s rift with the rest of the family, legal scandals, accusations of racism, financial scrutiny, then the death of the Queen herself.

In 2022, the incoming Australian Labor government — traditionally republican — bolstered the cause by appointing Matt Thistlethwaite as the first-ever Assistant Minister for the Republic.

Australia has come much closer to republican reform than Canada and New Zealand. In the 1999 republican referendum, 45 percent of voters opted to move to a republic.

For some republicans, this had been the great political cause of their lives. They still speak about it with great emotion.

Many republicans expressed a quiet confidence that the Queen’s death would trigger reform, or at least a renewed debate.

Support for Australia becoming a republic remains at similar levels according to recent polls.

But, as lawyer George Williams argued, waiting for the Queen’s death was “a bogus delaying tactic”. If constitutional reform was the right thing to do, Australians should not wait for events in the UK to trigger it.

The barriers for Australian republican reform remain high.

First, royal succession is automatic and legally protected. The moment one monarch dies, the next monarch succeeds. Constitutional monarchy comes with ideas of perpetuity baked in.

Second, passing a referendum in Australia requires a double majority: the majority of votes, in a majority of states. It effectively gives small states a veto, making reform by referendum so difficult former PM Robert Menzies said getting a yes vote from the Australian people was “one of the labours of Hercules”.

Third, while many Australians want reform, there is no sense of urgency and a general worry about the cost of change. Monarchists airily dismiss interest in constitutional reform as a liberal elite preoccupation and ask what would really change if Australia became a republic.

The research showed many Australians felt politically and emotionally attracted to republicanism but also had great affection and respect for Elizabeth II.

People do not seem to have the same attachment and reverence for Charles III — yet.

Enthusiasm for the new monarch might grow in the excitement of the coronation pageantry in May 2023 and any subsequent royal tour, as monarchists hope.

But it’s highly unlikely to be on the scale of Queen Elizabeth’s 1954 Australian tour, when reportedly three quarters of the population saw the young queen.

Compare this to the UK where the republican cause is muted, despite some popular misgivings about the royals themselves.

Canada, like Australia, has a written constitution requiring a very high level of public support to enforce change. The monarchy is far more part of Canada’s national identity than it is Australia’s. Monarchy is seen by many as a Canadian thing, one that does not conflict with ideas of Canadian independence and a confident national identity.

When New Zealand moves towards republicanism, it will be led by Māori. Possibly, as iwi (tribes) receive, through the Waitangi Tribunal, compensation for wrongs done to them, Māori will have less use for the crown as a treaty partner.

Some in the Waitangi Tribunal have suggested that in the 21st century the crown now stands for Māori as much as for pākehā (white New Zealanders).

And, under New Zealand’s unwritten constitution and unicameral parliament, the reform process could be as simple as a parliamentary vote.

In Australia, the monarchy retains an ambiguous significance in a country where many people remain committed to republican reform.

While republicans face stubborn opposition to reform from committed monarchists, the real threat is a public which simply has more pressing concerns.

A social anthropologist, Dr Sally Raudon is a Postdoctoral Research and Teaching Associate at Cambridge University. Her research focuses on death, citizenship, the body and sovereignty in settler states.

Her research cited in this article was funded by the Marsden Fund administered by the Royal Society Te Apārangi of New Zealand.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: The Crown as a constitutional symbol in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK