The response to Montana's TikTok ban reveals lawmakers' misconceptions about privacy and data security and hints at how they could get it right.

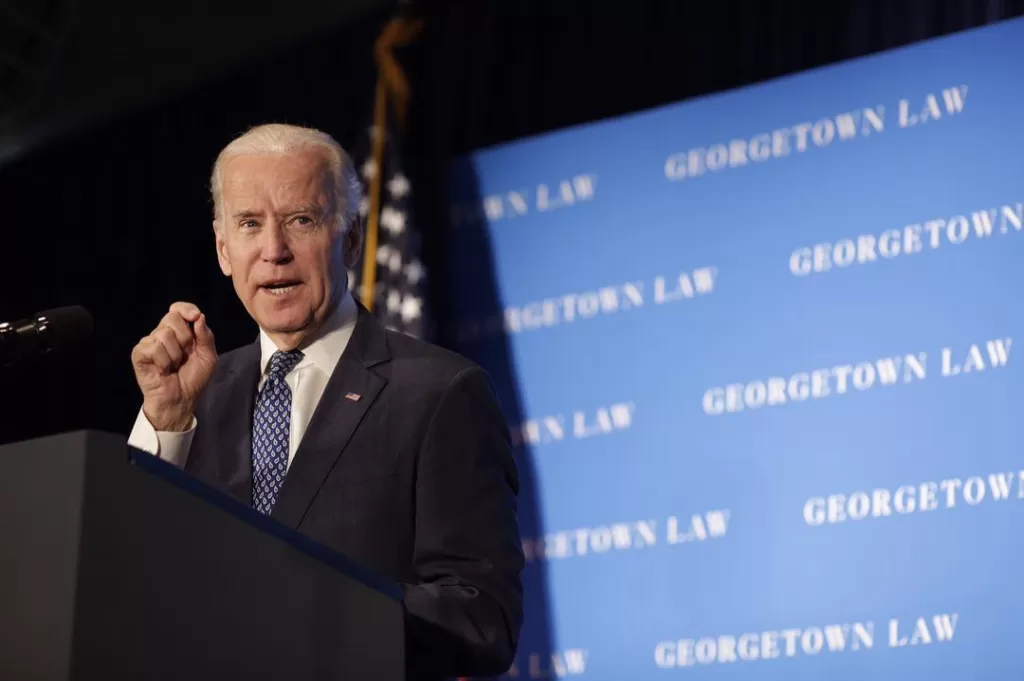

The US and China are in a tech war that has prompted a spate of tit-for-tat actions over TikTok : The White House, Wikimedia Commons Public domain

The US and China are in a tech war that has prompted a spate of tit-for-tat actions over TikTok : The White House, Wikimedia Commons Public domain

The response to Montana’s TikTok ban reveals lawmakers’ misconceptions about privacy and data security and hints at how they could get it right.

The tech war between the US and China has reached its most public battlefront as the back-and-forth between the superpowers over Chinese-owned TikTok reaches a boiling point.

It’s the latest clash in a cold war which started when China began its tech ascendancy in 2015.

Fuelled by a skilled and cheaper workforce, massive government subsidies and a willingness from investors to fund expensive manufacturing sectors, China has fast become one of the leading countries in tech and software.

The feud has prompted a spate of tit-for-tat actions over TikTok.

In August 2020, then-US President Donald Trump set in motion a ban on the app, which ultimately never materialised after Joe Biden came to office.

Since November 2022, TikTok has been banned on government devices across the US and Canada. In April 2023, the Australian government followed suit.

US lawmakers pushing for a full ban of the app claim the platform hosts harmful content and is a threat to younger users. They also frame the app as a risk to national security, allowing huge chunks of data to be tapped by the Chinese Communist Party.

But the appetite in the US to undercut the growth of TikTok speaks to an American discomfort with the Chinese-owned app’s rising market share, a sector traditionally dominated by the US.

The first salvo in the war was fired eight years ago with China’s ‘Made in China 2025‘ strategy, a 10-year blueprint to transform the country from a “manufacturing giant into a world manufacturing power”.

A key part of the plan involves corralling mass surveillance, big data and 5G technology to solidify the Chinese Communist Party’s domestic rule, creating an emerging state-led authoritarian regime.

It gives rise to two major worries from the US in its digital competition with China and other autocracies: the use of social media to collect and exploit personal data for political purposes and the spread of misinformation, propaganda and censorship.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has repeatedly said that control of big data will be critical to the next political and economic powerhouse.

Former US government officials say China is “winning” the war over data.

In part, it’s because of an asymmetry of access: Chinese entities have unfettered access to troves of American data through apps such as TikTok, while Beijing’s tight control over the internet in China prevents the US from doing the same.

Termed the “Digital Great Wall”, many Western websites are inaccessible on the Chinese internet. The list is long — social networks like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, as well as many Western news sites, blog platforms such as WordPress and search engines such as Google and Yahoo.

Instead, Chinese users are limited to homegrown products that try to emulate and sometimes compete with their big tech counterparts in the West.

Internet users in China don’t use Google, they search on Baidu, which has about 700 million users. Social networking and messaging is widely done on Weibo and WeChat.

The US retaliates through restricting tech companies rather than the websites themselves.

Huawei and ZTC are among the Chinese companies who cannot sell or import their products in the US, banned on the basis of weak circumstantial evidence.

When the US issued the prohibition, it did so because of the belief that China had no separation between the technology and data gathered in private commerce and in state-led military efforts.

This same thinking is fuelling tension around TikTok, an app which has more than 150 million monthly users in the US.

While the US targets short-term tactical assaults on China’s tech sector (a potential TikTok ban, draconian export restrictions on advanced semiconductor chips), China is building self-sufficiency, strengthening domestic science and technology and diversifying trade away from reliance on the US and Europe.

Partly, this means bilaterally recruiting developing economies as supporters and helping it build capacity, targeting nations dissatisfied with the American-led status quo.

It also means co-opting international bodies and redefining the principles that underlie them, like using World Trade Organization rules to boost exports while ignoring others which do not.

The aim of Chinese policy makers is not to make other countries more like China, but to protect China’s interests and set a standard that no sovereign government should bow to anyone else’s definition of human rights.

With many Western countries seeing a recent rise in populism and more liberal democracies turning inwards, losing interest in emerging regions, Chinese leaders see an opportunity to create a stripped-down, interest-based world order.

To some extent, the US and China are interconnected and dependent on each other — especially financially — which makes full separation of their economies impossible.

Excessive losses to one country will affect the other. Cooperation will happen, but it may be done with more caution and limited to areas where mutual benefit exceeds loss.

Economic rivalry between the countries is manageable, but a political conflict does not serve anyone.

The spectacle of TikTok bans in the US, underscored by a law in Montana that may be unenforceable and/or unconstitutional, risks becoming more of a political conflict.

Piotr Łasak (Ph.D., Hab.) is Associate Professor at the Institute of Economics, Finance and Management, Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. His research, publication and teaching activities focus on finance. Among the main research topics is the development of the financial market in China.

René W.H. van der Linden (MSc) is a senior lecturer and researcher in Economics, Finance and Business Research at the International Business programs of The Hague University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands. Together with Piotr Łasak, published at Palgrave Macmillan the pivots The Financial Implications of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2019 and Financial Interdependence, Digitalization and Technological Rivalries in 2023.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.