Quality research evidence points to what’s needed at both an individual and organisational level to stem the tide of burnt out health workers.

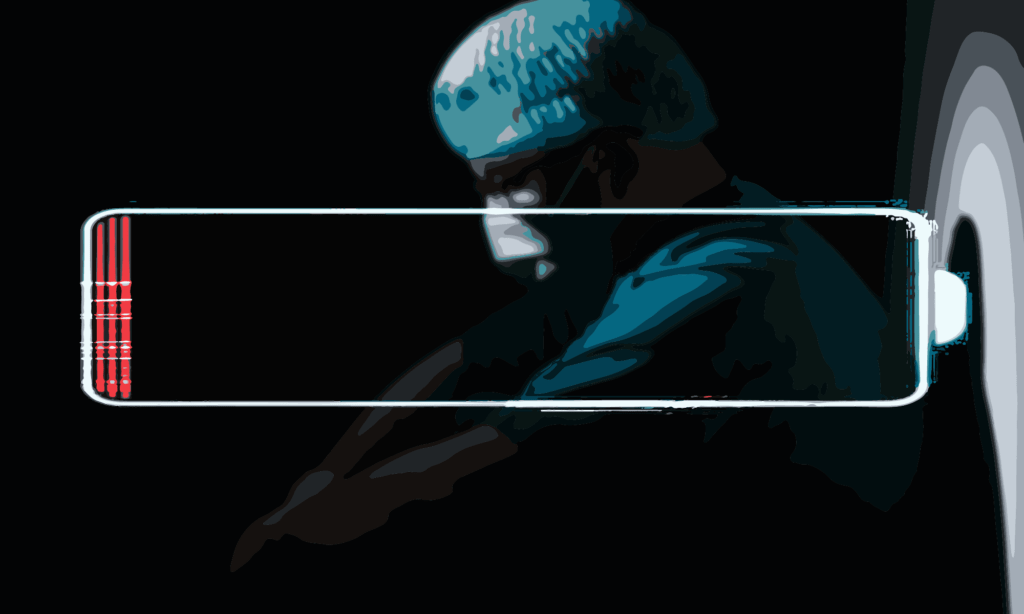

Health worker burnout hit new highs during COVID-19, but the issue existed long before the pandemic and will continue to be a concern for the entire community : Michael Joiner, 360info CC BY 4.0

Health worker burnout hit new highs during COVID-19, but the issue existed long before the pandemic and will continue to be a concern for the entire community : Michael Joiner, 360info CC BY 4.0

Quality research evidence points to what’s needed at both an individual and organisational level to stem the tide of burnt out health workers.

Emergency medical workers, already at increased risk for burnout compared to other professions, continue to be challenged by the fallout of COVID-19.

Stretched to breaking point by increased workloads, highly contagious and acutely ill patients and with limited resources, their risk factors for burnout have been amplified.

One obvious solution is to fix critical staffing shortages, but emergency health worker burnout was an issue before pandemic-driven staff shortages, and will likely continue into the future.

There is no easy fix, but the World Health Organization has been calling for action to better protect workers. Many are leaving the profession.

What is burnout and how prevalent is it?

Burnout is a workplace syndrome characterised by feelings of exhaustion, depersonalisation (a sense of detachment and that one’s surroundings are not real), and compromised work performance, according to the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases.

Researchers at the BlackDog Institute propose additional fundamental symptoms including lack of feeling, lack of concentration and lack of motivation, among others.

Burnout has previously been reported to be experienced by anywhere between 26 percent to 82 percent of clinicians working in emergency departments, much higher than other areas of medicine and the general workforce. But during the COVID-19 pandemic these figures were found to be consistently high, between 49.3 percent and 58 percent.

What does the research say about fixing it?

Despite the common self-help resources available online there is only a modest amount of high-quality scientific evidence for what works to address burnout in emergency medical workers.

Several systematic reviews of interventions broadly categorise interventions into two types: individual-focused – for example mindfulness or small group stress management education; and organisational-focused – for example limiting shift lengths, flexible working arrangements and building a positive workplace culture. Both types of interventions can lead to a meaningful reduction in burnout among health workers.

At the organisational level, a recent, high-quality study concluded organisations needed to take more ownership of implementing effective burnout reduction strategies to make workplaces less stressful and supportive of workers’ mental health.

There is also some evidence for job training and education, such as training by qualified psychologists on coping strategies, in reducing occupational stress and burnout compared to other organisation-based interventions.

A paper on the determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses found evidence of the need for a “good person-environment fit” where a person’s values, beliefs and personality traits match the norms of an organisation, to prevent burnout.

On an individual level, mindfulness-based interventions, in which people develop the ability to be present in the moment and not judge their experiences, have been found to be effective. Another study of nurse burnout also found implementing mindfulness-based interventions, as well as other positive thinking training, at regular intervals was key to ensuring long-term change.

Several studies have found a combination of individual- and organisational-level interventions have the greatest effect for general medical workers. For instance, studies have reported that implementing physician-targeted interventions like exercise and mindfulness techniques alone do not have a significant effect on burnout reduction but can be effective at reducing burnout when combined with organisation-directed interventions like good communication, interdisciplinary collaboration and team spirit.

Specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, studies of workers in ICU and ED found that work environment, communication, and support by supervisors had an established role in burnout both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

One study suggested organisations need to engage their workforces, listen to their concerns, and design targeted interventions based on the specific needs of their staff.

Finally, a study of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic found the psychological support health care workers receive significantly influences their feelings and emotions and can support their ability to handle the negative effects of such an event. It also found that social support from sources like family, friends, co-workers, and their organisation can help workers control and avoid negative feelings and emotions that can lead to burnout.

What are the caveats?

There are notable limitations in current research, for instance, evidence is limited about organisational interventions. Studies evaluating individual targeted interventions to reduce burnout are more common than organisational interventions because they are easier to implement.

Moreover, two studies found the overall sustainability of the effects of interventions is poorly understood. Lastly, a study focused on medical workers more generally that compared person-directed versus organisation-directed interventions found that some organisational interventions don’t target burnout directly or may have unintended effects on other factors that shape burnout.

For ‘The research on’ 360info works with experts to rapidly scan quality research and present the most current scientific evidence addressing global challenges.

The article is based on a rapid scan of systematic reviews focused on interventions to support emergency medical workers experiencing burnout, as well as interventions for medical workers more broadly. The scan was undertaken by a specialist Evidence Review Service at Monash University.

Alex Waddell is a health policy and systems researcher at Monash University and a final year PhD candidate researching the translation of Shared Decision Making from policy to practice through behavioural science.

Diki Tsering is a Research Officer within the Monash Sustainable Development Institute’s Evidence Review Service at Monash University.

Professor Peter Bragge is Director of Monash Sustainable Development Institute’s Evidence Review Service, which undertakes rapid reviews of research evidence to inform better decision-making in government, industry and other organisational settings.

Dr Paul Kellner is a Research Fellow and Associate Director of the Monash Sustainable Development Institute’s Evidence Review Service.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.