Parts of the United States have endured an epoch-defining megadrought, but continue to find ways to survive through a diverse policy-based response.

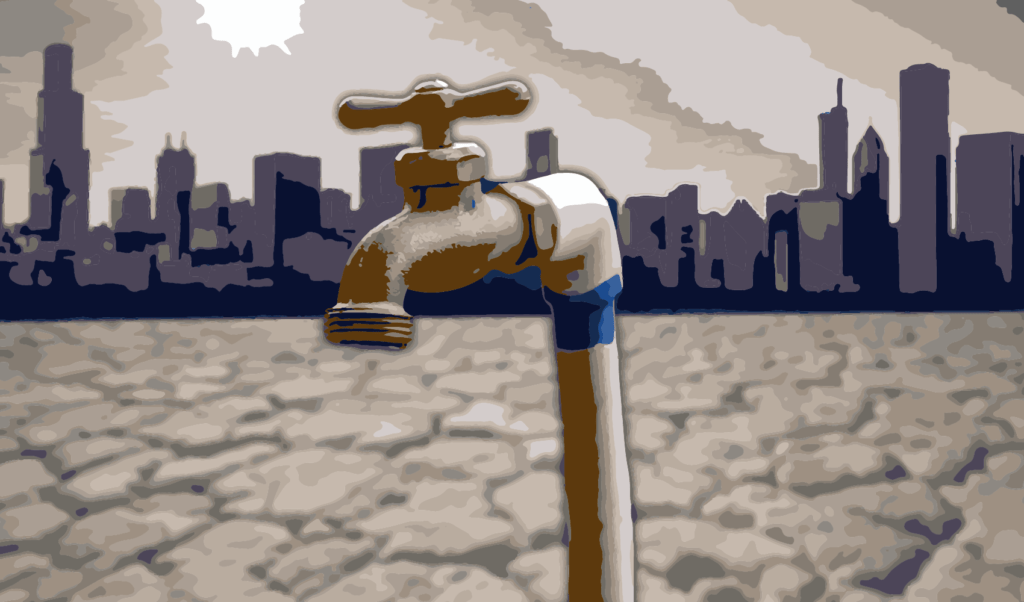

The frequency and intensity of drought is predicted to increase. : bummelhummel/pixabay Free for commercial use, no attribution required

The frequency and intensity of drought is predicted to increase. : bummelhummel/pixabay Free for commercial use, no attribution required

Parts of the United States have endured an epoch-defining megadrought, but continue to find ways to survive through a diverse policy-based response.

For two decades, the southwestern region of the United States has been in the grips of one of the most severe droughts of the last 1,200 years. It is a grave challenge to the most basic of rights: access to water, basic food production, and the habitability of cities. Policymakers across the country have needed to be bold and varied in their quest to secure water and draw upon the lessons of the past.

The causes of the multidecadal drought, often referred to as a ‘megadrought’, can be largely attributed to lower rainfall. The deficit is driven by natural variability in rainfall patterns, ocean dynamics in the tropical Pacific, and exceptionally warm temperatures.

Collectively, these phenomena have dried out soil, reduced stream flow, and created snow droughts. It has prompted a major decline in surface and groundwater resources, economic losses, ecosystem disruptions, and an increased risk of wildfires.

From January 2020 to August 2021, six southwestern states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah) experienced the lowest total precipitation and the third-highest daily average temperatures recorded since 1895. The weather pattern continued into 2022 and prompted governors in each of the six states to issue drought emergency declarations. The federal government issued an unprecedented water shortage declaration, ordering water restrictions along the Colorado River, a major source of water for agriculture and cities in the region.

The frequency and intensity of such droughts, and their cross-cutting and compound effects, are projected to increase as a result of climate change. In response, policymakers and water agencies across the southwest have developed new water management strategies to enhance local drought resilience. At the local level, such efforts are frequently nested within a complex inter- and intrastate institutional framework in which surface water supplies (as opposed to groundwater) are governed using an ‘appropriative’ system of water rights.

Administered by state-level agencies, the allocation of finite surface water flows is complicated by the diversity of competing stakeholders – social, economic, and environmental – intensifying discussions in dry times. Water management decisions at the local level may be hindered by state-level water restrictions enacted ad hoc, intergovernmental treaties concerning transboundary water resources, and environmental regulations.

Despite the challenges imposed by drought and the region’s Byzantine water policy structure, many of the southwest’s largest and fastest growing cities have been able to adapt and increase their drought resilience. Water has been conserved through both regulation and incentive-based programmes that focus on increasing the installation of water-saving technologies and transformation of urban landscapes from water-dependent turf lawns to drought-tolerant vegetation.

Residents and businesses located in San Diego, California, for example, have access to a variety of programmes and services facilitated by the San Diego County Water Authority (SDCWA). A wholesale water supplier, the SDCWA serves the city along with 23 other municipalities and water agencies located within San Diego County. The SDCWA’s WaterSmart initiative includes various rebates and educational resources to subsidise a portion of the costs to residents and businesses that invest in more water-efficient technology and landscapes.

In other regions, policymakers have taken a more heavy-handed approach to reduce the use of water-intensive turf lawns. In 2021, amidst the region’s most recent drought emergency, Nevada lawmakers passed an unprecedented law that banned “non-functional turf” in the Las Vegas area.

Efforts to reduce urban water use have been coupled with initiatives to enhance water supply diversification. The city of Phoenix, the fifth largest city in the US, largely relies upon water pumped across state lines from the Colorado River. However, the city also receives water in-state from the Salt and Verde rivers via the Salt River Project, which are generally less constrained than the Colorado River, as well as a small portion of water drawn from local groundwater reserves.

In 2003, the SDCWA took an innovative approach to diversify its water supply through a water transfer agreement with the Imperial Irrigation District, which provides water for irrigation to farmland located in southern California’s Imperial Valley. The SDCWA agreed to fund irrigation improvements for the District and lease the resulting water savings. With funding assistance from the state government, the SDWCA also lined two transfer channels to reduce water loss caused by seepage.

More recently, the city of San Diego and the SDCWA have also invested in water pipe monitoring technology to detect and repair leaks in the municipality’s water distribution system. Lastly, in 2015, San Diego County opened the nation’s largest desalination plant. The SDCWA entered a public-private agreement that will meet approximately 10 percent of San Diego’s water needs.

Water recycling has also played an increasing role in local efforts to increase water supply diversification. In 2019, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti pledged to recycle 100 percent of the city’s waste water by 2035. In Las Vegas, the Southern Nevada Water Authority captures and treats 99 percent of waste water from indoor use, putting it into Lake Mead, which provides about 90 percent of the Authority’s water supply. The remaining 10 percent is met through groundwater reserves. The city of Phoenix recycles effectively 100 percent of its wastewater, delivering it for uses in agriculture, energy production, urban irrigation, groundwater replenishment and river ecosystem maintenance.

In San Diego, two plants recycle approximately 8 percent of the city’s waste water for non-drinking uses such as irrigation and manufacturing. And in 2021, the city launched the Pure Water San Diego initiative that includes constructing two new plants to treat waste water to meet drinking water standards. The multi-year program aims to provide more than 40 percent of the city’s local water supply by 2035.

In response to the southwest’s persistent drought conditions, cities have undertaken multi-pronged approaches to enhance drought resilience. In some of the most arid locations, these efforts have been fruitful. From 2002 to 2020, per capita water consumption in the SNWA service area decreased by 47 percent, while the region’s population increased by approximately 52 percent.

Within the complex structure of western water policy, long-term, collaborative initiatives that span the public and private sectors and various levels of governance has led to this achievement. However, while the short-term outlook is positive, important questions remain concerning long-term sustainability considering the expected droughts to come and their short- and long-term effects on rural communities and the natural environment.

Duran Fiack is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Lehman College of the City University of New York. His research focuses on U.S. climate change mitigation and adaptation policy and planning at the state and local levels.

No conflicts of interest were declared in relation to this article.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.