Instead of adopting a tough foreign policy line, India must work to regain Bangladeshi people’s trust lost earlier.

Sheikh Hasina’s continuation in office is attributed to strong Indian support. : MEAphotogallery Flickr

Sheikh Hasina’s continuation in office is attributed to strong Indian support. : MEAphotogallery Flickr

Instead of adopting a tough foreign policy line, India must work to regain Bangladeshi people’s trust lost earlier.

On August 5 at 2:35pm (BST), a Bangladesh army helicopter took off from a helipad within the sprawling Ganabhan complex in Dhaka. Besides the pilot and two security officers, the only other passenger onboard was Bangladesh’s prime minister, Sheikh Hasina.

Just an hour before, Hasina had resigned after 15 years of uninterrupted rule marked by conflict-ridden politics, egregious human rights abuses, massive corruption and destruction of state and democratic institutions.

The olive-green chopper carrying Hasina lifted over the high-rise buildings surrounding Ganabhaban, landing shortly at the nearby Kurmitola airbase where she boarded a waiting C-130 aircraft with the call sign AJAX-1431.

The plane took off within minutes and headed west, landing at Hindon airbase in Ghaziabad near New Delhi. The Indian security establishment’s sanctuary to Hasina only exposed – and exploded – the myth that New Delhi does not interfere in Bangladesh’s affairs.

Hasina left behind a country in turmoil.

Barring the patchy presence of some army units, Bangladesh had no government for three days. In those three days, Awami League cadres and the party’s student front (Chhatra League) supporters engaged in bloody street-fighting with anti-government protesters and Jamaat-e-Islami and Islami Chhatra Shibir activists.

The clashes, which had started on July 14 as students protested against a job quota system that favoured Awami League followers, left nearly 500 dead and thousands injured across Bangladesh.

While some normalcy returned to Dhaka by August 7, other district towns and villages continued to be ravaged by miscreants and troublemakers, besides enraged supporters of other political parties opposed to the Awami League.

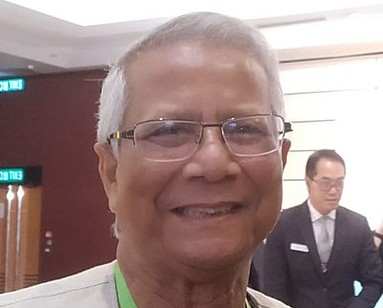

Yet, there was no sign of any legitimate authority in control until August 8 evening when an interim government led by Nobel laureate Mohammad Yunus took oath of office, even as New Delhi went ahead to pull out all its non-essential staff from its high commission and families of diplomats from Dhaka.

Hasina’s fall and swift ouster and the crumbling of the Awami League edifice has prompted forces such as the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Jamaat-e-Islami to step in to fill the political vacuum with a helpless New Delhi fulminating about an imminent takeover by extremist Islamist forces.

Caught by surprise

The high levels of violence and the subsequent disintegration of the Awami League took New Delhi completely by surprise.

For one, the Indians were either unmindful – which is unlikely – or deliberately ignored pent-up anti-India sentiments among Bangladeshis who found a section of New Delhi officials’ disproportionate softness towards a regime, which had committed human rights violations, indulged in corruption and destroyed democratic institutions, inexplicable and a reflection of binary diplomacy.

BNP leaders and political observers complained about India’s intransigence reflected in its “all eggs in one basket” approach towards Bangladesh.

Repeated reminders to the Indian establishment did not stir policy makers in New Delhi to change course in ways to engage transparently with all stakeholders for restoration of democracy and institutions in Bangladesh.

The Indian security establishment’s unstinted support of Hasina – when she was in power – was premised over a relationship in which New Delhi saw in her an ally who tried to neutralise extremist Islamist groups and helped eliminate some of India’s northeastern insurgent elements in the past.

Arguably, India-Bangladesh ties strengthened over the past two decades.

The bilateral relationship produced mutually beneficial results for New Delhi and Dhaka to recognise each other as development partners. While trade and economic engagement deepened, the two sides worked to enhance cooperation on cross-border security.

The relationship was mature enough to deploy mechanisms that resolved outstanding issues.

Hasina not only addressed Indian security concerns but also agreed to allow Indian rail transit through Bangladeshi territory.

However, it appeared that the advantages were tilted in India’s favour whereas Bangladesh’s concerns on Teesta River water sharing were left unaddressed by New Delhi.

In private, Bangladeshis fume over the Indian security establishment’s regular and routine interference in domestic politics and other key matters of state.

That Hasina could continue in power for three consecutive terms is attributed to the Indian security establishment’s alleged support of the Awami League during elections.

Bangladeshis’ negative attitude towards the Indian government found full expression when fraudulent elections were held on January 7, which returned Hasina to power for a fourth consecutive time.

The electoral contest was reduced to a farce when the Awami League fielded “dummy” candidates to contest against the party’s authorised nominees on a day when no more than 10 percent of the electorate voted across Bangladesh.

Earlier, the BNP boycotted the election, saying that the political atmosphere in Bangladesh was not conducive to hold free and fair elections. It demanded that elections be held under the aegis of a neutral, caretaker government.

India’s rock-solid support

Hasina’s ouster was preceded by nearly a year-long political upheaval over holding free and fair elections.

The United States sought to pressure the then Awami League regime to hold free, fair and violence-free elections. But India stood by Hasina, which was interpreted as a covert support for the regime. This was the proverbial last straw on the camel’s back, as far as Bangladeshi sentiments were concerned.

While the US came to terms with the outcome, the Hasina government sailed on even as there was no political opposition.

But the students’ agitation and demonstration gathered pace and expanded in mid-July following Hasina’s loose and insulting remark, describing the protesters as razakars (Bengalis who collaborated with the Pakistan army in 1971).

When the protests turned violent, Hasina responded with full force, giving the police and other paramilitary units free rein to shoot-to-kill. This ultimately proved to be disastrous for her and the Awami League.

Time for India to step back

As the Yunus-led interim government gets down to business – seemingly insurmountable given the deeply problematic, critical and controversial issues that need to be settled – New Delhi must take a step back and recalibrate, if not reconsider, its foreign and security policy options in Bangladesh.

It must shed its binary approach – supporting the Awami League over the other political parties – and convey its willingness to be a sensitive neighbour keen to engage with the interim regime across all policy issues. The adage “one cannot choose one’s neighbour” applies as much to India as it does to Bangladesh.

On its part, the Yunus-led interim regime must refrain from viewing India through the lens of suspicion and mistrust. Above all, both sides must now fall back on their people to return to the warmth and trust that existed several years ago. Building bridges is difficult but certainly not impossible.

Sreeradha Datta is Professor, Jindal School of International Affairs, O.P Jindal Global University, and Non-Resident Senior Fellow at ISAS-NUS, Singapore.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.