Some plants and animals love fire. Others do not. Science will help figure out which areas to burn, which to hose and how to create resilient ecosystems.

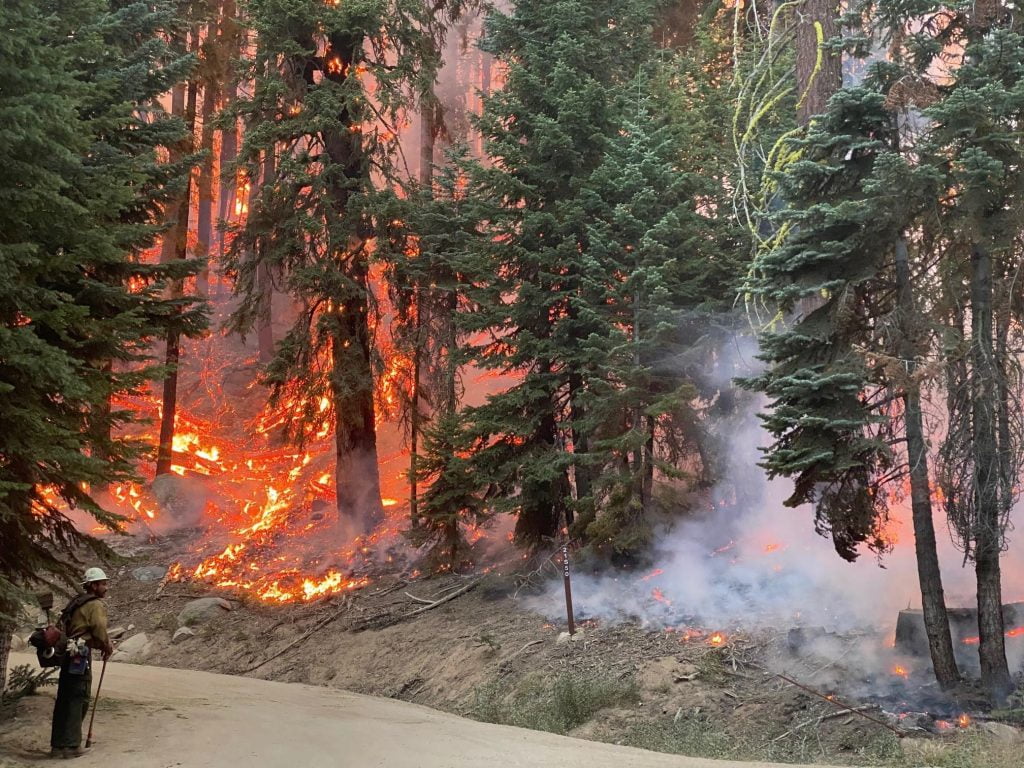

Fierce wildfires in recent years have further endangered the giant sequoia trees. : United States Forest Service

Fierce wildfires in recent years have further endangered the giant sequoia trees. : United States Forest Service

Some plants and animals love fire. Others do not. Science will help figure out which areas to burn, which to hose and how to create resilient ecosystems.

By Luke Kelly, University of Melbourne, Tim Curran, Lincoln University, and Sophie Wilkinson, McMaster University

The giant sequoias of California are some of the largest, oldest trees on Earth. Stretching 100 metres to the sky, some have a girth that could only be spanned by 20 friends holding hands. But in the last two years, fierce wildfires in California have killed an unprecedented number of these endangered trees. The fires in 2021 alone killed as many as 3,600 giant sequoias, which is approximately 5 percent of large trees in the population. The solution would seem to be to prevent fires, but sequoia groves thrive when small-scale fires pass through. Exclusion of fire can be just as harmful as too much fire.

Globally, more than 4,400 species face threats from patterns of fire that have been modified by human activity. Increasingly, researchers are exploring how climate change and land use are changing patterns of fire and what can be done to get more of the ‘right’ kind of fire.

Actively managing fire to suit particular species or ecosystems means ensuring the right amount, pattern, and timing of fire in landscapes that need it and less fire in those that do not.

Applying the right kind of fire can be helpful for both humans and ecosystems, encouraging desired species and resources. The continuation and reinstatement of Indigenous fire stewardship in the tropical savannas of Brazil demonstrates this. There, the Xavante people use fire to boost vegetation growth and certain animal foods. Areas managed by the Xavante are less likely to experience deforestation and weed invasion. Revitalising Indigenous knowledge in Australia, North America and beyond is likely to also promote patterns of fire that benefit biodiversity and people.

Collecting data through scientific experiments and systematic monitoring encourages innovative fire management. For example, knowing when plants flower and produce seed can be used to identify when fire is needed, and parts of the landscape where fire should be suppressed. Linking such information with projections of future wildfires provides a powerful way to design more effective planned burning strategies. In semi-arid Australia, computer modelling has been used to investigate whether planned burns can reduce the risk of harm to birds, reptiles and small marsupials. Preliminary studies indicate that strategic burns, including burning in a striped pattern, can moderate the size of wildfires and benefit some threatened species.

A new strategy in many temperate forests is letting wildfires burn when conditions are not extreme, to promote patchily burned areas that are helpful for a range of species. In Yosemite National Park, California, a policy of not extinguishing fires started by lightning has created more diverse habitats that support a variety of plants and their pollinators, such as bees.

A different suite of approaches focuses not just on fire, but on the whole ecosystem. Fire and biodiversity cannot be tackled in isolation from other environmental changes such as habitat loss or introduced pest species.

From the Arctic tundra to the Amazon rainforest, large-scale environmental restoration projects involving local communities and national agencies have been proposed to increase the total area of habitats and their connectivity to each other. In general, bigger and better-connected animal and plant populations are more resilient to fires.

The boreal region of Canada is home to a wide range of creatures, from microscopic microbes to massive moose and caribou. But draining the spongey peatlands has increased the risk of very large fires and tough-to-manage smouldering fires that persist even in cold conditions. Strategic rewetting of drained peatlands and the promotion of fire-resistant mosses can create a natural fire break, reduce wildfire severity and promote biodiversity.

In Africa, reintroducing native grazing animals such as white rhinoceros helps to create patchy fires. The grazing of these huge creatures creates habitats for a range of insects and plants. Of course, context matters; grazing by non-native animals, such as cattle in Australia’s alpine regions, doesn’t always reduce fire risk and can harm ecosystems.

Some ecosystems may even benefit from artificial habitats. In the Simpson Desert of Australia, scientists have tested the use of refuges made from wire mesh in providing shelter for small animals in open, recently burnt landscapes. Ongoing research indicates that these ‘safe houses’ could protect populations of reptiles and small mammals that would normally be easy prey for introduced cats and foxes.

To protect sensitive plants from high-severity fires, Australian rapid response teams have recently trialled the deployment of sprinklers and an American team trialled wrapping the famous giant sequoias in fire-resistant foil.

Restoring and promoting landscapes that people can use creates opportunities to balance land for wildlife with other values in many regions of the world. On every vegetated continent, scientists are partnering with local communities to explore ‘green firebreaks’ comprising low-flammability species planted at strategic locations across the landscape. Research in New Zealand has identified low-flammability vegetable crops, pastures and traditional Māori food and medicine species, such as the kawakawa tree, that could moderate fire while enhancing biodiversity.

Agriculture and forestry around the Mediterranean that promotes patchworks of low-flammability crops, orchards and oak trees can also reduce the risk of large, intense fires and provide homes for communities of threatened birds.

Science has provided a large body of knowledge on fire and biodiversity. At its best, science is inclusive of the diverse people living and working in fire-prone ecosystems. Learning from previous and current management by local and Indigenous people and fostering shared fire management are invaluable steps in promoting fires that benefit people and biodiversity. But more large-scale experiments are needed to test new ideas.

And on top of all the other changes humans are creating, climate change is increasing wildfire activity and causing more extreme fire weather in many parts of the world. The challenges the world faces in a new era of fire are so large that ecologists need to keep experimenting, testing new ideas and being bolder with conservation initiatives. Ecosystems are shaped by complex and interconnected reactions to humans and fire. As the world changes, it’s an interplay scientists need to keep learning about.

Luke Kelly is a scientist who studies ecology and evolution in fire-prone landscapes.

Sophie Wilkinson works at the interface of academia and industry to develop novel fire management techniques in boreal and temperate regions.

Tim Curran studies plant flammability to address a range of applied and fundamental topics, including the identification of low flammability species to help redesign landscapes to mitigate fire hazard.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.