Attracting much-needed investment into the blue economy can be spurred by tailor-made initiatives.

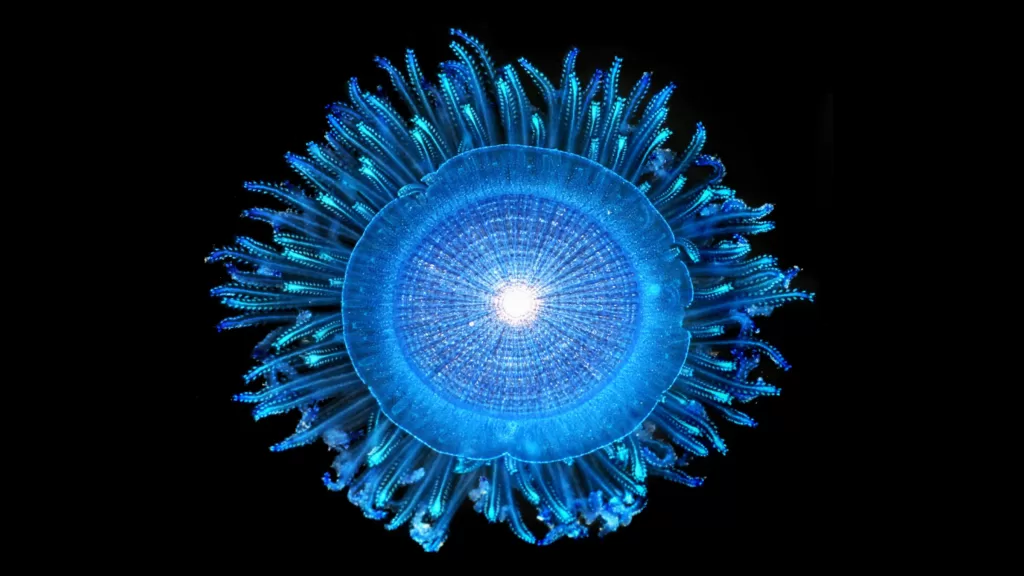

Funding for the blue economy remains a challenge in various parts of the globe. : Flickr: Pedro Ribeiro Simões (https://www.flickr.com/photos/46944516@N00/218617130) CC BY 2.0

Funding for the blue economy remains a challenge in various parts of the globe. : Flickr: Pedro Ribeiro Simões (https://www.flickr.com/photos/46944516@N00/218617130) CC BY 2.0

Attracting much-needed investment into the blue economy can be spurred by tailor-made initiatives.

The ‘blue economy‘ has global significance. Eighty percent of global trade relies on maritime transport. Approximately 40 percent of the world’s population resides in coastal regions and over three billion people depend on the oceans for employment.

The ‘natural capital’ of the blue economy holds an estimated value of around USD$25 trillion while the annual value of goods and services produced amounts to approximately USD$2.5 trillion.

Despite the immense potential, financing the blue economy remains a challenge, hobbling its full promise.

The funding needed for achieving Sustainable Development Goal 14 ‘Life below water‘ is estimated to be approximately USD$174.52 billion per year. However, the current annual expenditure only amounts to around USD$25.05 billion, a massive shortfall of USD$149.02 billion per year in funding.

Inadequate fiscal policies, a drop in development assistance, limited private investment and, in some countries, the presence of significant external debt burdens are all holding back the blue economy

Upscaling the blue economy is also confronted by the need for consistent concessional financing sources, the limited capacity of authorities which implement projects, investor concerns related to the financial viability of the project and the newness of customised financial instruments.

Another obstacle in attracting investment into blue economy sectors stems from inadequate institutional, regulatory, governance, legislative and human resource frameworks, all of which are necessary to establish robust partnerships.

Among the 17 SDGs, goal 14 has received comparatively less funding than other SDGs. However, green finance instruments, blue bonds or blue sustainability-linked loans can be extended to support blue finance. Additionally, markets for blue carbon are experiencing growth.

To ensure a smooth transition of finance from green initiatives to blue initiatives, it is essential to build capacity within the financial sector on a fundamental understanding of the ocean economy and risk assessment.

The approach of uniting the financial sector with the real economy through blue finance as a catalyst for change can then be replicated across various underfunded sectors within the ocean economy.

This includes industries like fishing where vessels are not primarily aligned with a net-zero trajectory. Aquaculture and mariculture also face significant vulnerabilities to coastal inundation and extreme weather events. Coastal insurance is another area that can benefit from this approach.

To expedite investments in the oceans, tools like the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles introduced by the UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative can play a crucial role.

The involvement of philanthropy and impact investors is also gaining traction. Numerous prominent philanthropic organisations based in the United States have shown interest in the ocean. Family offices, impact investors and dedicated funds focused on the ocean and its economy are beginning to emerge.

There is considerable potential for impactful initiatives and collaboration between these investors, governments and businesses to scale up and coordinate outcomes. However, this potential remains largely untapped.

Different strategies for blending finances will be required at different phases of blue economy projects. By applying the stages of a typical project life cycle to blue economy initiatives, one can identify the specific type of financial support necessary.

During the construction phase, affordable, low-cost and long-term financing is crucial. Partial risk guarantees and first loss protection for a specific portion of assets can help. Once the ‘risky’ period is over, financing can be optimised using take-out financing instruments.

It is essential to tailor the financial instruments based on the project phase and its characteristics. To speed up the availability of finance for the blue economy sector, it is important to segment and target investors appropriately, aligning them with the respective financing instruments.

Education, public awareness and capacity development play a vital role in fostering behavioural and lasting transformational change as well as establishing the necessary governance structures within the blue economy.

One breakthrough for the blue economy was achieved in March this year when after 15 years of negotiations, a significant treaty concerning the High Seas was successfully reached at the United Nations in New York.

Much like the climate and biodiversity-focused Conferences of the Parties, a similar framework for oceans will be established through this agreement.

The introduction of the High Seas Treaty is certainly positive. However, it remains crucial to promptly evaluate and prioritise maritime activities and investments in a well-balanced manner, encompassing various jurisdictions and areas of the ocean that lack governance.

While most governments have implemented policies and plans to shift away from fossil fuels towards achieving the targets set by the Paris Agreement, there is a notable lack of coherent strategies for supporting the blue economy.

This is worrying considering that many countries heavily rely on the oceans for food, energy, transportation, and livelihoods. There is a need for tools like blue finance that serve multiple purposes in the blue economy.

These tools could aid in assessing the value of the blue economy, establishing appropriate arrangements and frameworks for investments and formulating strategies to safeguard and improve marine ecosystems while addressing competing interests.

It is crucial for nations to allocate investments towards the oceans as part of their Nationally Determined Contributions and plans for coastal resilience. Countries can collaborate to safeguard areas of significant global biodiversity and ensure sustainable and fair access to resources.

Oceans are a potential catalyst for future growth in developing regions, particularly through ventures such as wind energy, offshore aquaculture, seabed mining and marine genetic biotechnology.

The blue economy holds enormous potential for sustainable development but unlocking it requires substantial financing and strategic investments. Overcoming challenges related to funding gaps, capacity limitations and inadequate enabling frameworks is crucial.

Blending finances, tailored instruments, and collaboration among various stakeholders can drive the growth of the blue economy and ensure a sustainable and prosperous future for both people and the planet.

Raghu Dharmapuri Tirumala is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne. He declares no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.