Both Indian law and society need to change to counter the current stigma felt by members of the queer community.

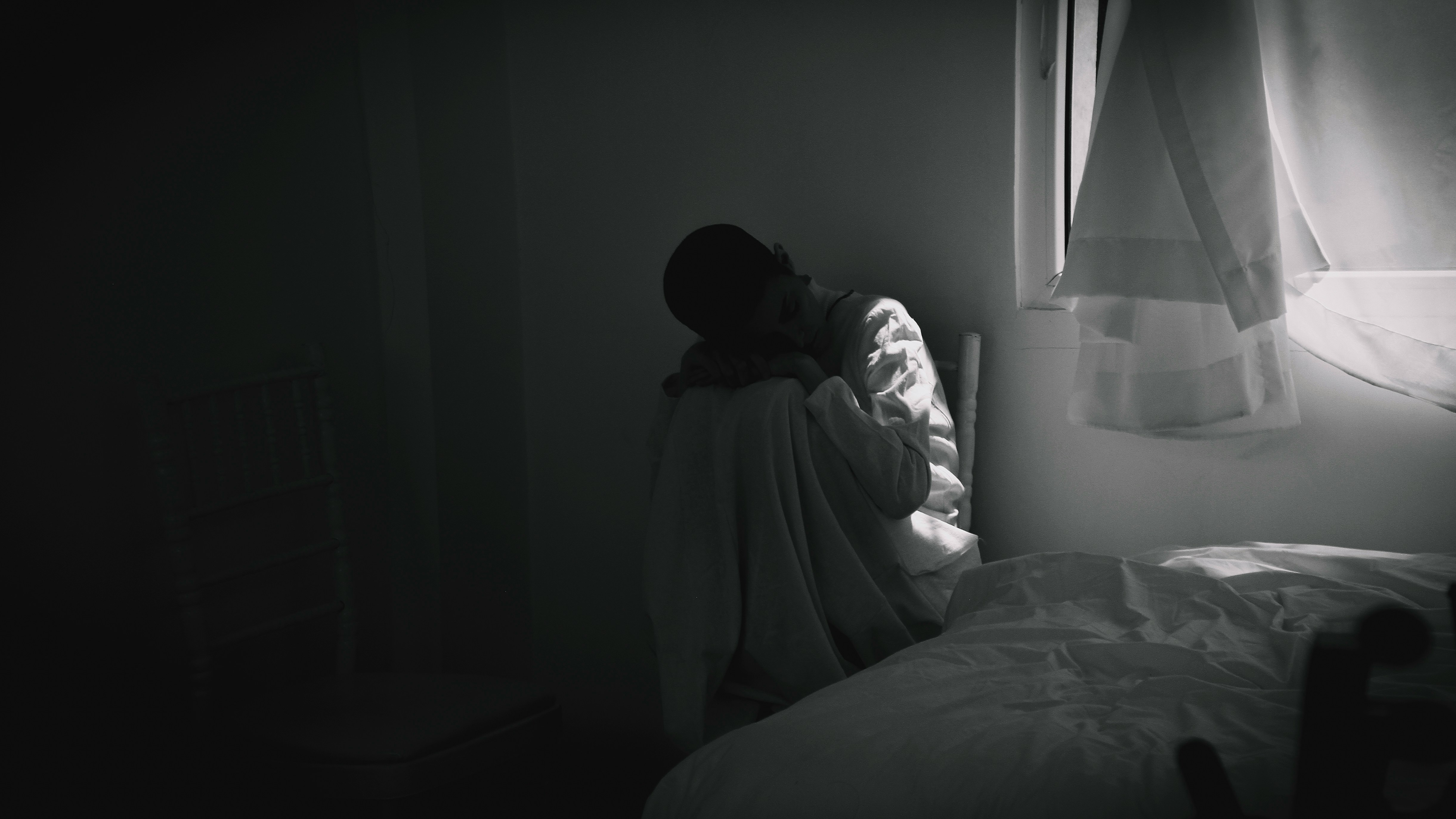

For gender and sexual minorities, structural loneliness accompanies their survival due to the way society places limits on their very existence. : Aashish R Gautam Unsplash

For gender and sexual minorities, structural loneliness accompanies their survival due to the way society places limits on their very existence. : Aashish R Gautam Unsplash

Both Indian law and society need to change to counter the current stigma felt by members of the queer community.

For Pri, a Hyderabad-based gender-nonconforming legal advisor, traditional gender roles and expectations isolate those who do not conform. This isolation has led them to think about attempting suicide and they express shock at reaching the age of 30.

These traditional expectations extend to cultural and professional spaces, exacerbating feelings of incompetence further due to their identity as a neurodivergent individual.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, queer individuals are 2.5 times more likely to experience mental health issues than their heterosexual counterparts.

In India, this disparity is compounded by a challenging legal and social landscape.

Despite India’s pride in its rich cultural history, its societal structure remains heavily patriarchal and centred around marriage being between a man and a woman. This binary system is deeply ingrained in the fabric of the country.

However, historical accounts sporadically document non-heteronormative individuals, challenging the myth of a strictly binary heterosexual society.

Legal progress is happening but stigma remains

India has made significant legal strides regarding queer rights. In 2018, the Supreme Court abolished Section 377 in the Indian Penal Code, which criminalised consensual same-sex relations. The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act was passed in 2019.

However, social stigma continues to plague queer lives.

Hate speeches, unreported hate crimes, murders through people meeting on dating apps in small towns, lack of family acceptance, social media trolling, and jokes about nonconformity in popular culture make life difficult for queer individuals.

While the loneliness epidemic among LGBTQIA+ individuals is well-documented in the United States, similar data is scarce in India.

Research in the US indicates that loneliness can be as harmful as smoking.

In India, the loneliness epidemic is gradually gaining recognition, but for gender and sexual minorities, structural loneliness accompanies their survival due to the way society places limits on their very existence.

Interviews with community members reveal the depth of this issue.

Babli and Chanda, transwomen aged around 45 begging at traffic signals in south Delhi, say that while they are now recognised by the government, societal acceptance is lacking. Chanda speaks of the fear and disgust they encounter when approaching people, highlighting society’s hypocrisy.

Despite being willing to work for a regular income, they face widespread employment discrimination. They are legally recognised only on paper as the “third gender”, a term that reinforces their marginalisation rather than acknowledging their humanity.

According to the 2011 census, 31 percent of transgender individuals in India commit suicide, and more than 50 percent attempt suicide before the age of 20. Chanda and Babli attribute this to societal loneliness, as they struggle to find housing, food or even water due to their stigmatised identities.

A social activist, R, points out that the Trans Rights Act of 2019 fails to address the gaps identified by the 2014 National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) judgement. The authority had filed a case for India to legally recognise genders beyond the male-female binary. The verdict has been called the most progressive judgement in Indian history and recognised transgenders and their fundamental rights, including its implementation by states.

The new act does not appropriately cover sexual abuse against trans individuals. Sexual abuse committed against transgender people and men is not criminalised under the Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita legislation, whereas Section 377 previously provided some protection under the Indian Penal Code.

Social stigma isolates people

Beyond legal issues, social stigma remains a significant barrier. On July 2, the Kerala High Court acknowledged that family spaces are “sites of abuse” for LGBTQIA+ individuals, places where they can face violence and harm.

Saroyi, a non-binary individual from the state of Uttar Pradesh in northern India says: “My parents are progressive in many aspects as we already are a lower caste and understand discrimination. However, I fear telling them this aspect of my life that I am not a man, a male body yes but a non-binary individual who likes different genders sexually but a woman. I fear getting thrown out of my family; who will I call my family then? I fear that they would not want another factor that generates marginalisation for the family. I keep returning to the closet when home, performing as a male, and it has been a serious concern for my prolonged depression for many years.”

In smaller towns, the stigma is even more pronounced due to a lack of knowledge and understanding. Saroyi describes the overwhelming patriarchy and rigid gender roles.

Marriage, the strongest binary system, shapes one’s identity, and deviation from these norms results in social shame, family disownership and financial instability. This isolation drives individuals to extreme actions as financial stability is often only achievable by conforming to their assigned gender at birth.

Shafiya, a queer social science student, says that while coming out to family can help, the pressure to conform to traditional gender roles remains.

They also mention the loneliness within the queer community that leads to mental and physical distress, guilt, shame, body image issues and existential crises.

Rohit, a 20-year-old gay man from a small town in Uttar Pradesh, reiterates this: “I do not see me in movies; we have no texts in school about us; I had no idea in school what was happening to me. Sex education is the bare minimum in schools. Homosexuality devastates your head; I could not ask anybody. The narration on the internet is so mixed and filled with English stories. My parents are not educated and if they don’t find positive stories from their family, friends or in newspapers, how will they know I exist like this and not in a conventional idea of marriage? I will be married off. This is lifelong isolation.”

Healthcare also remains largely inaccessible for queer individuals.The HIV epidemic initially stigmatised LGBTQIA+ individuals incorrectly as the sole bearers of the condition. Beyond HIV, hormonal therapy and gender-affirming surgeries are still out of reach for many, and day-to-day healthcare is limited due to societal stigma and discrimination within the medical community against them.

Towards a solution

Addressing queer loneliness requires creating inclusive spaces.

For legal advisor Pri, therapy and friendships within the queer community have provided them with a sense of belonging. Shafiya finds solace in student political groups that challenge societal norms.

A queer psychologist in South Delhi says that coming out to family and achieving financial stability has given him the confidence to live on his terms. Saroyi and Pri emphasise the importance of friendships over romantic relationships in combating loneliness.

However, the most significant policy measure to include LGBTQIA+ individuals equitably could be to include them in school curriculums. Success stories, healthcare needs and societal stigma all exist, and if discussed in school, a young child going through puberty will not be left confused or isolated. These young children will go to different professional spaces and bring about the necessary changes needed to reform these institutions from within, especially in the medical field.

Ultimately, queer love alone will not save us from loneliness.

The giant leap of structural change, a sense of community and spaces to exist, not just in urban areas but also in suburban and rural spaces, can help those who feel isolated.

Chanda and Babli observed that the least society can do is view them as human beings and provide them with basic human rights. Even if society does not celebrate them, they should have an equitable platform to exist.

By acknowledging and addressing the structural loneliness faced by queer individuals, India can move towards a more inclusive and supportive society.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, visit https://findahelpline.com/i/iasp.

Dr Nikhil Sehra is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social and Political Studies at Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies, Faridabad. Their research focuses on identity, nation, caste, subaltern studies and cultural studies.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Loneliness epidemic” sent at: 11/07/2024 00:00.

This is a corrected repeat.