Learned optimism can be a game-changer in climate negotiations

A change in approach can help developing countries challenge the historically negative outcomes of the negotiation process and adopt a positive outlook

If developing countries perceive their shared hopelessness in climate negotiations as temporary, the response can be proactive consensus-building instead of blame-shifting. : Dario Daniel Silva Unsplash

If developing countries perceive their shared hopelessness in climate negotiations as temporary, the response can be proactive consensus-building instead of blame-shifting. : Dario Daniel Silva Unsplash

A change in approach can help developing countries challenge the historically negative outcomes of the negotiation process and adopt a positive outlook

In a recent book, environmental lawyer Svitlana Romanko speaks of a Ukrainian movement towards a permanent embargo on Russian fossil fuels, oil and natural gas companies.

Founded amid the Russia-Ukraine war, it aims to accelerate the global transition to clean energy, even as annual UN climate conferences move slowly towards convergence in negotiations between developed and developing countries.

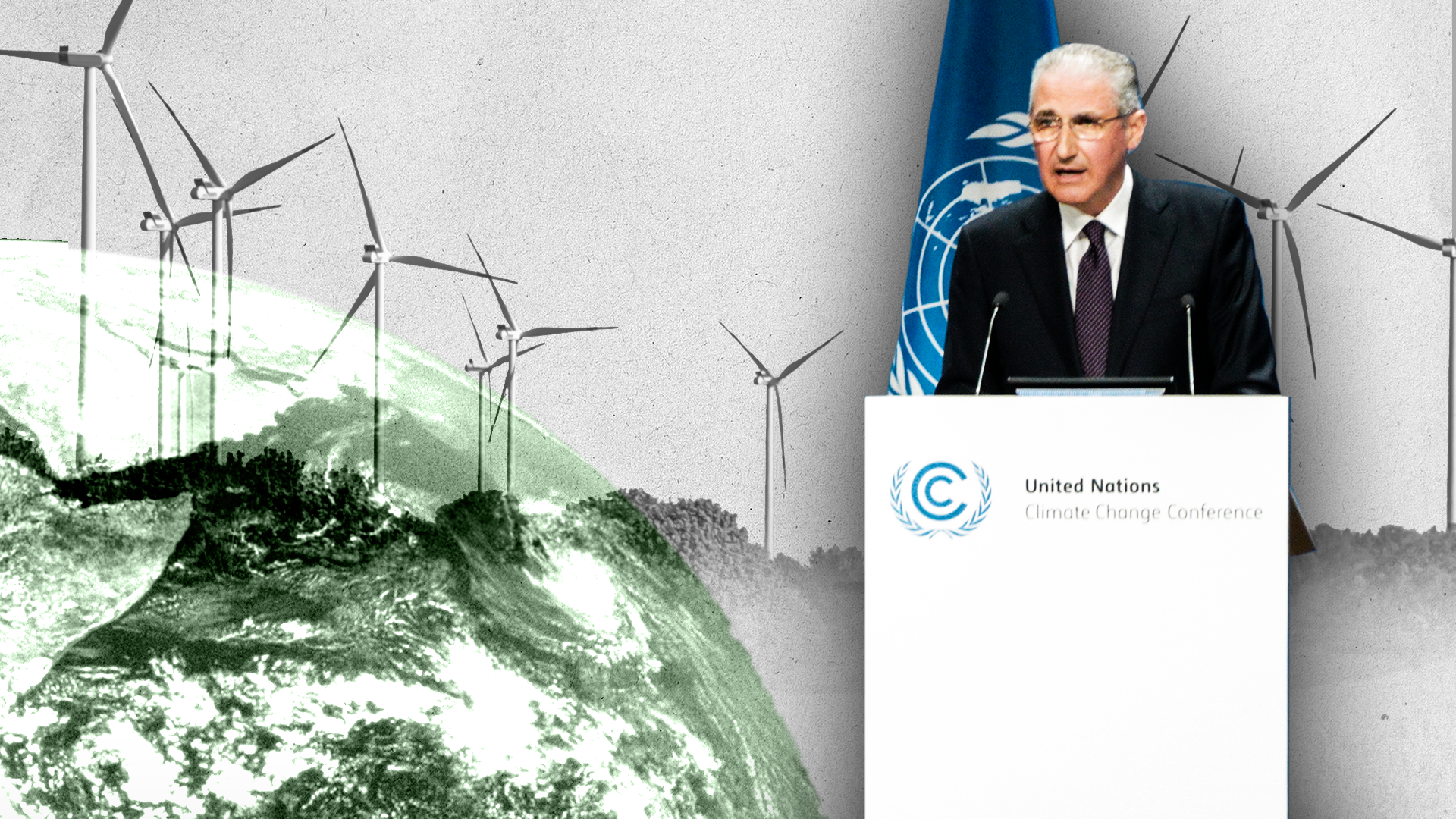

This is an example of the complexities that COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, must navigate amid a global polycrisis.

The larger context of climate negotiations reflects passivity and a sense of hopelessness, even as some hope still exists of control over the situation.

The success of these discussions may well depend on whether climate negotiations remain in a state of learned helplessness.

The question is how this attitude can be changed to one of learned optimism.

Four objectives

The four main objectives of the discussions largely revolve around funding for programmes already agreed upon.

The New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQGCF) seeks to increase financial support for developing countries to tackle mitigation and adaptation efforts based on previous finance goals under the Paris Agreement.

The second objective is operationalising Article 6 of The Paris Agreement to enable the functioning of global carbon markets for catalysing climate action, enhancing capital markets and ensuring resource flow to developing countries.

The other objectives are building on the progress of COP27 and COP28 for operationalising the Loss and Damage Fund for the support of vulnerable communities in Small Island Developing States and strengthening international cooperation on carbon markets, nature-based solutions and clean energy transitions for addressing global climate ambitions.

Hope or hopeless

The term “learned helplessness” was coined in 1967 to describe a psychological state in which an individual, through repeated exposure to uncontrollable negative events, starts to believe they are powerless to change their situation, despite the ability to do so.

This question can be posed in the context of global climate politics and justice in relation to developing countries when it comes to operationalisation of the COP29 agenda.

Providing climate finance from developed to developing countries has been quite slow. The minimum amount of climate finance has been $US100 billion per year, which needs to reach at least $US6 trillion to address the climate mitigation and adaptation goals.

This slowness can create despair and helplessness within the developing and small island countries who have not received the desired funds from developed nations.

The rise of conflicts and crises across the world and other geopolitical tensions have only contributed to this slowness and enhanced their despair.

Shared despair

After 1967, through various experiments, Maier and Seligman reasserted that a situation of hopelessness occurs when one perceives a lack of control over negative outcomes.

The history of climate negotiations, non-ratification by the US and the stubbornness of developed and industrialised countries towards reaching a global consensus of common but differentiated treatment — the idea of developed and developing countries working towards emission reduction for the common goal of saving the earth but with consideration given to their varying development histories — since 1992 is testament to this.

This perception has strengthened across various groups of developing countries when it comes to climate negotiations.

However, the tide of global politics has started to change due to India’s emerging power and the global climate goals and ambitions set by India at the Glasgow summit .

Additionally, the rise of the BRICS nations — with the inclusion of the African Union in the G20 group of nations — and regional groups composed of ASEAN, the Indo-Pacific Islands and Middle-East and Arab countries are clearly changing global power politics.

This has had an impact on global climate politics.

A persistent effort from developing countries with a leadership role played by India, the UAE and others during COP27 and COP28 brought in a consensus within the parties to focus on loss and damage functions and resources for addressing loss and damages in the developing and Small Island Developing States who will bear most of the burden of climate change impacts.

The responses of the developing countries to their situation of shared helplessness can go in two directions. If perceived to last long, their response to the climate negotiations will be pessimistic at COP29.

However, if the developing countries, led by the stronger economies such as India, UAE and Brazil, perceive this helplessness as temporary and are willing to change, the response will be proactive consensus-building instead of blame-shifting.

Towards positive outcomes

Climate negotiations, especially since the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, have marked a rise in the self-esteem of developing countries during the negotiation process.

A change in standpoint to negotiate on focused agenda points without deviating on multiple areas of concern also shows a positive response.

If they maintain this stance in the upcoming summit, promising outcomes can be expected, though the impact of larger geopolitical conflicts from traditional security risks of countries cannot be completely ruled out.

However, at COP29, developing countries also have to consider to what extent a sense of optimism in the negotiation process will be most beneficial.

An attitude of shifting blame and attributing the success of negotiations only to one party’s doing can be problematic.

One way developing countries can evolve from learned helplessness is through learned optimism — challenging the historical negative outcomes of the negotiation process and adopting a positive outlook for the future by considering the changing global political order.

This can also avoid a situation of shifting blame and despair in the negotiation process. Instead of internalising the experiences of failure, learned optimism means pledging to take responsibility for failures in future.

The implications of this can be realised through executing the transfer of climate finance from $US100 billion to $US6 trillion for developing countries.

Amidst the geopolitical risk and uncertainty, the upcoming COP 29 still can emphasise the importance of empowering past experiences, learning from them and putting the goals of COP29 into action.

Anandajit Goswami is a Research Director at Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies, Independent Visiting Fellow at Ashoka Centre for People Centric Energy Transition, Ashoka University and Honorary Visiting Professor at Impact And Policy Research Institute.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.