Pathaan successfully propagates a masculine state, but also pitches for a country in need of healing.

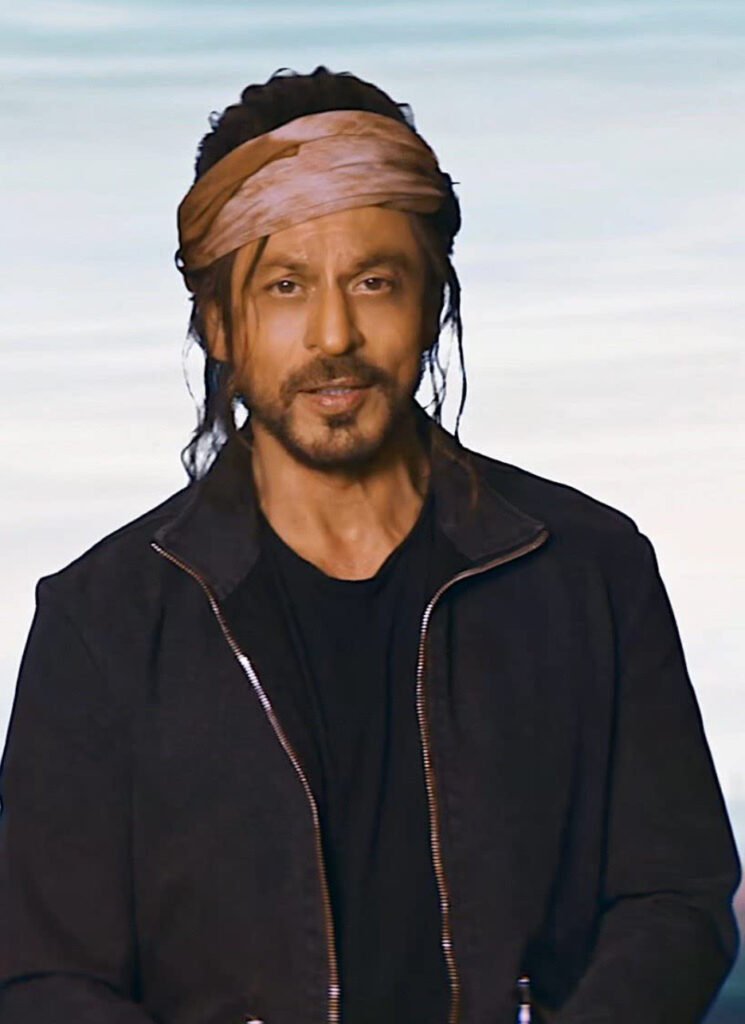

Shah Rukh Khan : IMDB CC BY-SA 4.0

Shah Rukh Khan : IMDB CC BY-SA 4.0

Pathaan successfully propagates a masculine state, but also pitches for a country in need of healing.

Cinema has always faced the simple question of whether it is aligned with propaganda. The answer, however, is enormously complicated. To accept the idea would mean, among other things, accepting that thrillers canvass on behalf of murder, classical melodrama promotes weeping women and musicals publicise exuberant outbreaks of choreographed gestural articulations.

However, that is not generally considered the case for any of them. One might argue that the assignments of each of these well-wrought genres go beyond the sensorium of spectatorial responses natural to them. In fact, there are now insightful studies about why Hollywood flooded its global footprint with musicals during WW-II; why hard-boiled detectives soothed the distressed American nerve in the Depression-era, or why science-fiction cinema flourished in the age of the Cold War space-race. Similar concerns have attended the works of Sergei Eisenstein or Dziga Vertov in the Soviet Union, and more explicitly that of Leni Riefenstahl in Nazi Germany.

One of this year’s Oscars favourites, All Quiet on the Western Front, is part of a long line of films which have pleaded for an end to war-induced violence, cruelty and conflict. Should we then call them propagandists for peace? Or is propaganda something that is just wicked and political, and hence needs to manufacture consent through cinema?

These issues have occupied Hollywood scholarship for a while now. The question is whether there is a similar imperative hidden in Bollywood films.

Popular cinema in India has been largely a self-perpetuating machine, clumsy in utterance, wanton in consumption, and cluttered in its everyday presence. And yet its popular heft is beyond any doubt. There is not much disagreement with the idea that it has been, for many decades, a naive and unforced vehicle of humane, if not always progressive, values that came clothed in wholesome entertainment.

But neoliberalism and the consequent ascent of the right-wing as both as an institutional and a cultural force may have made it subliminally politico-propagandist. For example, two recent films among many middling others — Uri (2019) and Kashmir Files (2022) — were unambiguously right-wing, made with the explicit purpose of influencing public opinion. So, are we to infer that neoliberal Bollywood has ingrained itself with the Indian state in preference over its historical ethos that was grounded in a multicultural Indian nation?

It might be interesting to investigate the case of the Shahrukh Khan vehicle Pathaan which merges the video-game format, Marvel-like idiomatic spy universe and Mission Impossible-scale action sequences with South Asian concerns of pop-geopolitics, identity and religion. It takes the task of balancing a purported statist agenda with a gigantic stardom, especially under the circumstances in which Sharukh Khan has faced relentless right-wing vilification in recent years. It would not be an exaggeration to say Pathaan presents a case of competing claims that mirror the tensions of the current Indian political discourse.

In the introduction to their edited collection SRK and Global Bollywood, Dudrah, Mader and Fuchs give a hint of what Shahrukh Khan or SRK as he is popularly known, as a carrier of popular signification, might mean. They write, “SRK not only represents globalised polysemy in the characters he plays on-screen, but also in his entire ‘celebrity ecology’ that includes visual, material, textual, oral, commercial and non-commercial, personal and public components working in tandem.” This has only grown since.

However, this time, and more than any time earlier, a counter campaign of right-wing trolls was also pressed into action with the sole purpose of deflating the box-office promise of Pathaan. Why? Because SRK had to be pulled down from the talisman of being a Muslim megastar in a Hindu-majority nation. However, the opposite has happened. Pathaan has already grossed over USD$135 million worldwide, making it the second-most successful Hindi film of all time. This raging success has bolstered Pathaan’s case as a kind of totem of Bollywood in the present.

Pathaan is a fit candidate to ask if it embodies or subverts a specifically Bollywood kind of propagandic tendency, but not for its commercial success but because of its furtive self-awareness. On the face of it, the eponymous Pathaan is the centrepiece of India’s robust and secretive state security machinery, protecting, as spies do, the country from international (read Pakistani) terror. He goes on a globe-trotting hunt for Jim, the professional terrorist super-villain, who is commissioned to wage biological warfare on Indian people by a rogue official of Pakistan’s intelligence-wing, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

This thrill-a-minute drama has a ridiculously familiar plot, with stunts that are at war with reason; heart-stopping chases, racy song-and-dance interludes, crisp storytelling and cheeky humour. In other words, Pathaan is every bit that over-the-top potboiler where the typical excesses of popular storytelling merge seamlessly with stunts and VFX from Hollywood. In terms of its official rhetoric, it ticks the right boxes: ISI, Pakistan, Kashmir, a lean and alert state machinery, incorruptible officialdom, dedicated custodians of national honour etc.

But at heart, Pathaan is also a spoof, because it makes fun of this very premise, incorporating references that are self-consciously clever. An hour or so into the film, our hero reveals that he is an orphan and was abandoned at a cinema hall (of all places). He also mentions that his name was a referent for an entire clan, for it is at a Pathan village in Afghanistan that Pathaan was given a new life after being heavily wounded in a proxy-war.

The second revelation is a clever ploy to deny Pathaan a stable identity, especially one anchored in religion. The first entirely subverts the orphan trope in Indian cinema by making Pathaan’s birth non-denominational. But there is also that hint that SRK’s Pathaan was born in the sovereign republic of cinema itself and Pathaan, as an imaginary character, and Shahrukh by enacting the same, are most functional in that republic.

Pathaan falls in love with a Pakistani spy, does not fetishise Pakistan as a rogue country; does not overemphasise India’s geopolitical dominance; or babble the easy rhetoric of jingoism. In a sequence that comes in the middle of the end-titles, Shahrukh and co-spy Salman Khan (as superspy Tiger) regale at their ageing heroics, and decide they must continue to be the custodians of their nation in spite of their age. This refers to younger spies but it is impossible to ignore the symbolism; for they are also India’s two reigning Muslim superstars and can barely hope to pass the mantle of safeguarding the country’s fundamental ethos to those unaware of its dignity and beauty.

Pathaan has successfully propagated a masculine state, but also bandied for a country in need of healing. That the public embraced this message, participated in the cheekiness of an imaginary cinematic republic, held aloft a dimpled (and greying) hero and danced with Pathaan all the way shows the nation may not be yet ready to let the warm waters of the Indian popular become amenable to the cold wishes of a hawkish state.

Sayandeb Chowdhury teaches in the School of Letters, Ambedkar University, Delhi. More about his work and interests can be found at https://sayandeb.in/.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.