How political parties have influenced our desire to own our own homes.

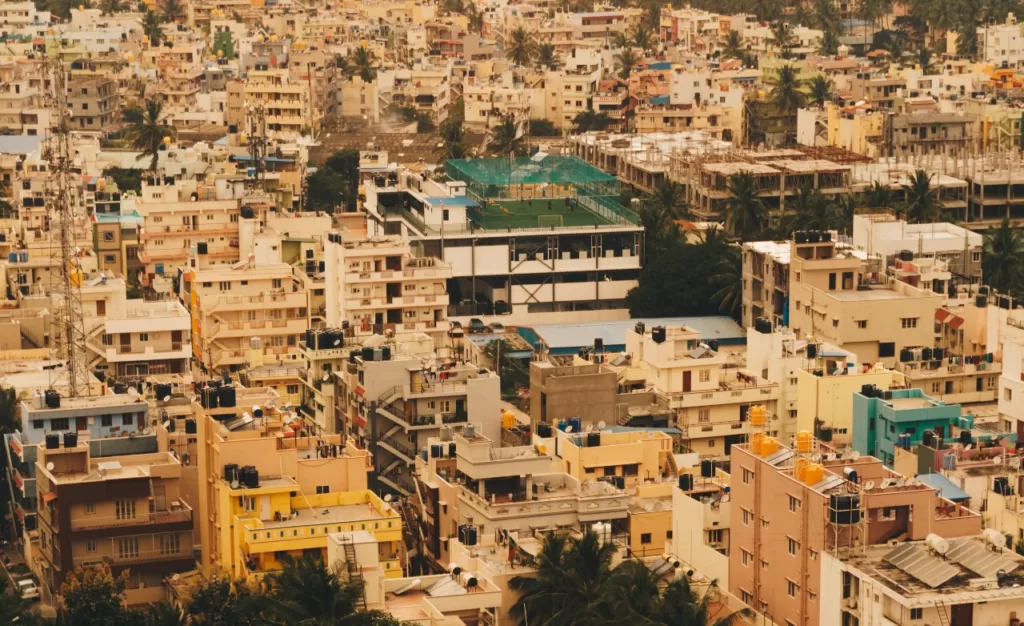

Owning your own home increasingly feels out of reach for many. : Unsplash: Tom Rumble Unsplash Licence (https://unsplash.com/license)

Owning your own home increasingly feels out of reach for many. : Unsplash: Tom Rumble Unsplash Licence (https://unsplash.com/license)

How political parties have influenced our desire to own our own homes.

In the late 20th century, in most countries and even cities in the world, the majority of residents were homeowners.

Some 20 years later that picture has shifted considerably, leading many to question whether home ownership remains an achievable dream.

While European cities had for centuries been inhabited by large tenant majorities, they joined most other countries in a gradual rise in home ownership across the last century, pushed by sales of public housing units.

Formerly socialist countries rapidly joined the homeowners club through the giveaway of state and cooperative apartments to sitting tenants after 1990.

When asked about their ideal housing arrangement, most households in developed economies have persistently dreamed about owning a, preferably single detached, family home.

This is particularly pronounced in the Anglosphere where approximately 40 percent of people in the UK and 30 percent of people in the US reject living in an apartment in a three to four storey building, according to a recent YouGov survey.

The dream of widespread home ownership has not only been a personal but also a political dream, cherished by political parties throughout almost all democratic and even authoritarian countries.

In developed economies, the modern idea to spread home ownership among the broader population, particularly the working classes, can be traced back to a rent-to-buy scheme for family houses with a garden in the French textile town of Mulhouse in the 1830s.

Local employers and the municipality sought to tie mobile workers to one place, keep expenses low and counter-revolutionise the incipient labour movement.

It is no wonder that Friedrich Engels attacked this model in his famous The Housing Question series of articles published from 1872 to 1873.

Engels anticipated the erosion of the working classes through home ownership and considered housing a bad kind of private welfare, as housing equity is lowest when unemployed workers would need it most.

The home ownership idea started a long intellectual career among social reformers through the World Exhibitions of the 19th century and eventually entered the party platforms of virtually all conservative parties, as an analysis of almost 2,000 party platforms in 19 countries showed.

Given the enormous gap between wages and housing values, however, the idea was not realised — with the exception of the more realistic garden allotments or Schreber-gardens — before mortgage credit became widely and cheaply available and purchasing power rose in the 20th century.

Home ownership was defended in party manifestos for being the bulwark against socialism, giving workers a stake in society, lowering housing costs after retirement and strengthening families.

After 1945, the political support for home ownership pervaded almost all party platforms, when most labour and social democratic parties jumped on the bandwagon as their members and voters became more upwardly mobile.

As a result, the tax system in more and more countries tended to favour ownership over renting: by not taxing imputed rents (or the rent you would pay for the house you own and live in if you were renting it instead), allowing mortgage payments to be deductible from income taxes, and exempting capital gains in housing from tax.

Since the Global Financial Crisis however, fewer younger households have been able to realise the home ownership dream due to tightened credit conditions, rising house prices and, lately, the rise in interest rates.

Researchers have spoken of the 2010s as the decade of a new generation rent, particularly in the costliest cities for housing.

After the subprime crisis, party positions in favour of homeownership started to recede and the ‘myth of home ownership’ was under public attack.

Sprawling single-family houses, unaffordability and intergenerational inequalities, and a lack of other alternatives were some of the problems identified.

With the disappearance of an effective social housing alternative in most countries, the private rental sector saw an unexpected comeback.

On the housing supply side, this comeback was enabled by new institutional landlords ranging from asset managers, insurers, private and public pension funds.

With privatised pensions in ageing societies growing, returns on traditional government bonds being low, these investors have contributed to making rental housing a new kind of asset class.

Even if home ownership rates are still far from being down to pre-1900 levels, home ownership rates have fallen considerably in the last 20 years and may decline further in some projections.

And with them the common belief in the unquestioned merit of policies that advocate for home ownership at the expense of all other alternatives.

Professor Sebastian Kohl is the Head of the Department of Sociology in the John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies at Freie Universität Berlin. His research focuses on the political economy of housing and the insurance sector, both in historical-comparative perspectives.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.