The Russia-Ukraine conflict, the Israeli invasion of Gaza, and Chinese aggression in the South China Sea are likely to require greater action from New Delhi.

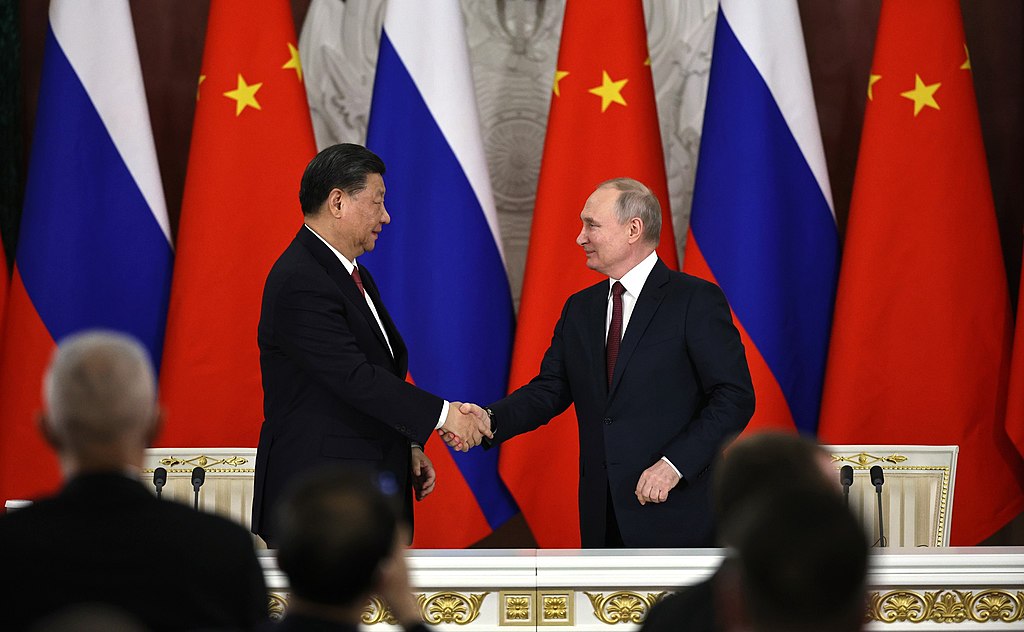

China’s Xi Jinping and Russia’s Vladimir Putin. As Russia and China get closer, India has to reconsider its relationship with the former. : Presidential Executive Office of Russia CC BY 4.0.

China’s Xi Jinping and Russia’s Vladimir Putin. As Russia and China get closer, India has to reconsider its relationship with the former. : Presidential Executive Office of Russia CC BY 4.0.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict, the Israeli invasion of Gaza, and Chinese aggression in the South China Sea are likely to require greater action from New Delhi.

India’s global standing and its capacities beyond its borders are becoming part of the aspirations and identity of a small but influential number of Indians.

This is an important reason, among others, why foreign policy is becoming an ever more important part of the range of issues India’s apex leadership has to devote attention to.

Unsurprisingly, India’s present political leadership has sought to use foreign policy for domestic ends. One could argue that the Balakot air strikes against Pakistan on the eve of the 2019 general elections were not exactly “foreign policy” given that Pakistan is often shorthand for signalling in domestic politics.

However, the effort expended by the outgoing government in promoting last year’s G20 summit in New Delhi as some sort of coming-of-age event for India suggests a more developed effort to make foreign policy part of the domestic conversation.

The three ongoing conflicts that currently dominate the international headlines — Russia-Ukraine, the Israeli bombing of Gaza, and Chinese aggression in the South China Sea — are likely to require greater action from New Delhi than mere posturing as has been the case so far.

Ukraine war creates a dilemma

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine created a dilemma for India in having to pick sides between Russia, an old partner and major military supplier, and the United States, a new friend with whom it shares a common adversary in China.

India chose to neither throw its lot in with the West nor be entirely uncritical of Moscow. It raised its concerns privately with the Kremlin while its combative External Affairs Minister, S. Jaishankar, batted away questions from the Europeans, especially, about India’s position.

It is worth remembering that this was also a performance that won admiration from a section of the Indian domestic audience for the government’s willingness to stand up to the West and its refusal to be lectured.

However, with Putin’s latest visit to China and the special bonhomie on display during that visit, it is clear that the Russia-China relationship is the most important bilateral relationship for both countries as they struggle with their domestic and international challenges.

The incoming Indian government will now need to carefully reconsider its relationship with Russia. Can New Delhi strengthen existing bonds with Russia if Moscow is so heavily dependent on China? For India, Russia is too far away, and China, too near — India cannot pressure Russia to support it in its contest with China but China can put pressure on India at any time.

While Jaishankar has declared that India would “not let China dictate the play…”, the fact is that this is precisely what has happened in the past decade at least on the Line of Actual Control between the two countries.

Whether it is in terms of China’s military transgressions on the Line of Actual Control or in the negotiations following the Galwan clash in 2020, it is the Chinese that have set the pace. What little India has achieved by way of disengagement at various friction points on the Line has required a long, hard slog.

Any new government will have to figure a way past this stasis and achieve forward movement quickly if China is not to convert its post-2020 advantages into permanent gains.

But going by the manifestos of both the major national political parties – the ruling BJP and the opposition Congress – there is no such plan of action evident.

Nuance on Israel-Gaza

The Israel-Gaza conflict has far greater domestic resonance in India with sections emboldened to support unequivocally Israel’s violent, months-long response to the October 2023 terrorist attack by Hamas, no matter that the targets are no longer the terrorists themselves but innocent civilians.

Despite Narendra Modi’s initial support for Israel, New Delhi has come around to a more nuanced position. This said, India is, at best, a bit player in the conflict dynamics and will prefer things to stay that way.

Unlike an earlier era, New Delhi is not particularly interested in intervening regularly in the conflict, even if only diplomatically. If the political colour of the incoming Indian government does not change, status quo on this issue is likely to continue.

Responding in the South China Sea

In the South China Sea, New Delhi has begun to respond to China’s actions.

While its regular deployment of naval vessels to the region for exercises and port calls do not yet signify any significant capacity to intervene directly, the sale of its BrahMos missiles to the Philippines indicates a newfound willingness to push China’s buttons, at least from a distance.

Closer to home, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh recently announced that India would not stop at just three aircraft carriers but would build “five or six more”, indicating concerns about China’s growing activity in the Indian Ocean. Whether New Delhi will finally agree to give the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, better known as Quad, more military teeth remains to be seen.

There are several global issues where India is an important voice in international discussions but which do not necessarily grab domestic attention in India – climate change, cybersecurity and AI governance, and multilateral trading arrangements to name just a few.

In climate change negotiations, irrespective of the electoral outcome, India will continue to insist on common but differentiated responsibilities for developed countries, China, and other developing countries.

On questions of regulation and governance in the fields of cybersecurity, AI and other frontier issues, India will insist on having a say, whatever its actual capacities in these domains.

In international trade negotiations, however, it remains to be seen if India will adopt a more open-minded approach willing to take on short-term pain for its domestic industries as the price to pay for greater integration into the global economy.

The more likely scenario will be one in which India will continue to insist on other developed economies opening up to services from India in return for greater Indian participation in multilateral trading arrangements.

New Delhi appears to believe that it has the leverage to either get developed economies to agree to its terms in exchange for market access or to achieve its goals through mini-laterals focused on specific interests or issues.

For a variety of factors – including their government’s actions – the Indian public is freshly attentive to Indian foreign policy.

The new Indian government will have plenty on its plate that requires urgent attention and consistent engagement.

For far too long have rhetoric and incremental steps been the default mode for Indian foreign policy practitioners. A world in flux and increasingly divided between two camps will require India to become more active and to signal its positions more clearly if its ‘strategic autonomy’ is not to be considered merely a cover for conservatism or a lack of courage to make hard choices.

Jabin T. Jacob is Associate Professor, Department of International Relations and Governance Studies, Shiv Nadar University, India. X: @jabinjacobt.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Indian election” sent at: 23/05/2024 07:59.

This is a corrected repeat.