Action from the world's top courts against Israel and Hamas leaders proves we are in a new age of increased relevance for international law.

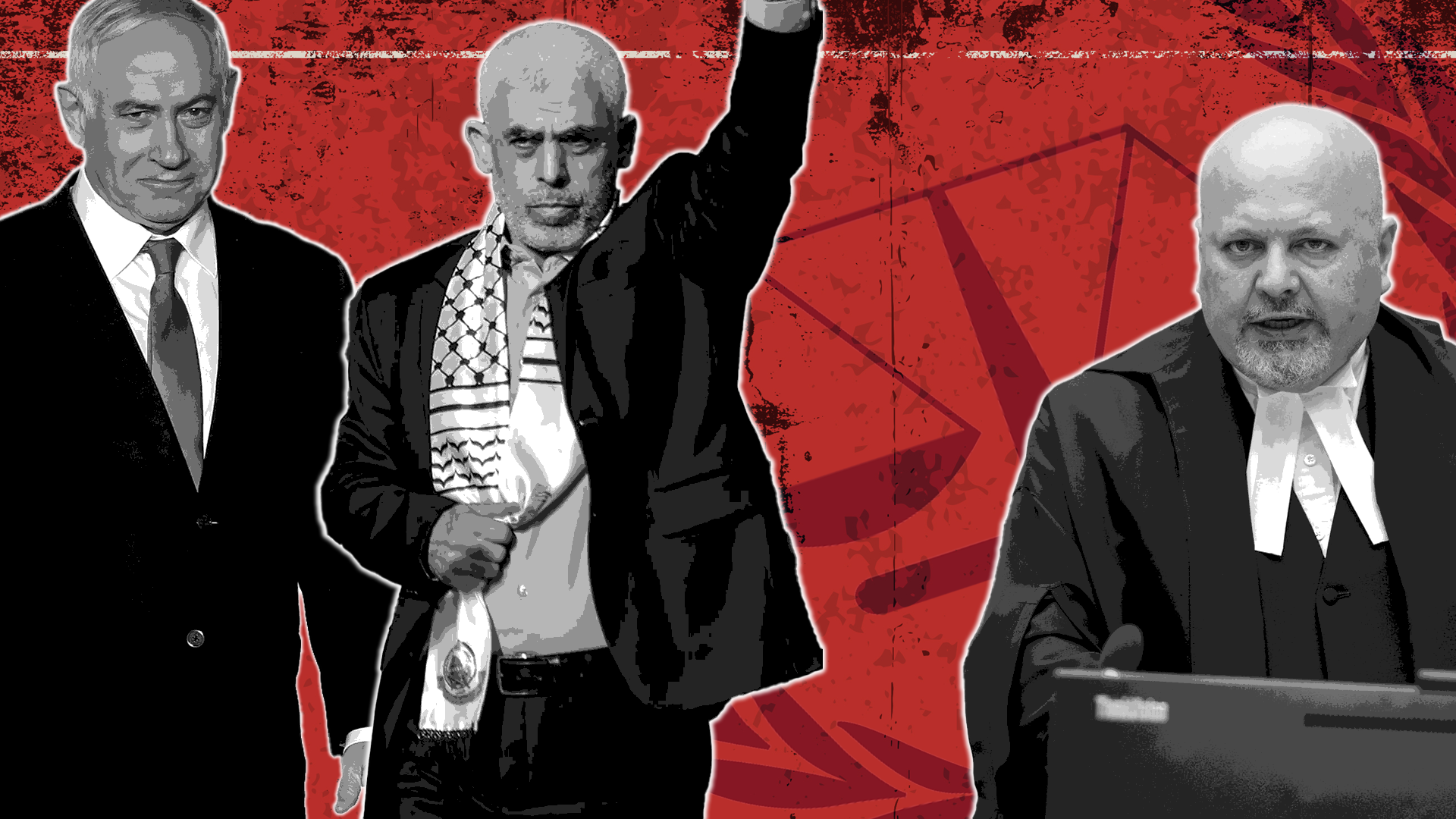

The International Criminal Court’s Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan : UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia CC BY 2.0

The International Criminal Court’s Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan : UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia CC BY 2.0

Action from the world’s top courts against Israel and Hamas leaders proves we are in a new age of increased relevance for international law.

On June 6, 2024, Spain applied to the United Nations to join South Africa’s case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which accuses Israel of committing genocide in Gaza.

Just a day earlier, the US House of Representatives passed a proposed law to sanction the International Criminal Court (ICC) in response to the latter’s seeking actions against Israeli leaders Benjamin Netanyahu and Yoav Gallant for suspected war crimes in Gaza.

These two developments are the latest in a series that has placed international law at the centre of the war in Gaza.

The involvement of the world’s top courts has given more visibility to the war, while also raising expectations that the ICJ and the ICC will halt the war, punish those who’ve violated the rules of armed conflict, and deliver a modicum of justice to Palestinians in Gaza as well as the victims of Hamas’ terror attacks.

However, neither the ICJ’s orders nor the prospect of arrest warrants from the ICC has caused Israel to change its tactics. As civilian suffering in Gaza has intensified over time, questions have emerged about the relevance of international law. There is also an impression that international law has failed in this context.

But this impression is misplaced. Law is frequently violated even in domestic contexts where states have enforcement agencies. There are no analogous enforcement agencies in the international arena. So, to expect international law to prevent wars or significantly alter the behaviour of a strong belligerent like Israel is to expect a little too much.

This does not mean that international law has been ineffective. On the contrary, it has been instrumental in shaping the contours of geopolitics, morality, and justice in the context of this war.

First, consider geopolitics. The language and substance of international law have mediated emerging West-non-West and intra-Western dynamics around the war. South Africa’s genocide case has resonated widely across the non-West, including with Global South heavyweight Brazil and the regional player Egypt, a BRICS+ member.

Against a rapid decline of the West’s normative power, several Global South countries have used international law to mount a collective critique of Israel and balance the support of its Western backers with solidarity for Palestine. In the process, these countries have potentially increased their normative influence vis-à-vis the West.

The Western notion of the rules-based international order has come under close scrutiny. Here, ‘rules’ have been equated with the rule of international law, which has allowed Global South leaders to call out the West’s double standards on Ukraine and Gaza.

People are asking how the Bucha massacre in Ukraine was a violation of international law while the mass graves in Gaza are not. The question is being asked: if Russia’s leader Vladimir Putin is an alleged war criminal, why is Israel’s leader Benjamin Netanyahu not? This inconsistency has deepened the West’s credibility crisis, shearing away its moral edge over Russia and China in international affairs.

The European Union’s outgoing foreign policy chief Joseph Borrell recognised the problem early. In November last year, he expressed concern that the EU was ‘suspected of applying double standards regarding international law between Ukraine and Israel-Palestine, particularly from countries of the so-called Global South’. He asked the grouping to correct this impression.

The EU has continued to be remiss but there is churn within Europe, not least because the continent has long defended itself as the champion of international law.

For instance, the dilemma over how to respond to what seems like a clear violation of international law from Israel has struck Germany, arguably Europe’s most steadfast supporter of Israel. If a warrant is issued for Netanyahu’s arrest, Berlin’s existential commitment to Israel will be pitted against its fundamental commitment to international law.

Spain, Ireland and Norway have also recognised Palestinian statehood. This development was unlikely to have happened if Europe’s strong tradition of identifying within international law and Israel’s military behaviour had not clashed so starkly.

In addition, the pre-existing normative gulf between Europe and the US has also widened in recent weeks. While the two are strategically one, they differ deeply in their approaches to international law as well as sensitivity towards the sentiments of the non-West.

Finally, America finds itself in a bind. American expressions of concern over Israeli behaviour have involved a call for its ally to respect international law — as well as a one-off admission that Israel may have violated international law.

However, the US position has become complicated in the aftermath of the genocide case. Even if the political and ideological compulsions that make the US support Israel were to disappear, the risk of being seen as complicit in genocide — on account of its military support to Israel — would prevent it from being candid.

Second, consider morality. The moral dimension was present from the start with Hamas’ terror attacks followed by Israel’s deadly response, both of which involved civilian killings. The argument that then emerged was that civilian harm was unacceptable regardless of the justness or unjustness of Hamas’ quest for ‘self-determination’ and Israel’s for ‘self-defence’.

However, after the ICJ determined that Palestinians in Gaza were at risk of genocide and asked Israel to desist from potentially genocidal actions, and followed it up with an order asking Israel to stop the Rafah invasion, the allegation that Israel may be executing a genocide has gained strength.

It has reverberated on the streets of Western capitals, on university campuses, and in some legislatures, in Australia and the EU, for instance. Over 300 Australian civil servants have asked the Australian government to ‘end its support of the genocide’ in Palestine.

For decades, Israel had enjoyed an exceptional moral status because of its identity as a state of a people who had survived genocide in World War Two. That status had allowed Israel to get away with excesses against the Palestinian people. But the fact that there is a Genocide Convention and an international court has found Israeli actions as falling within the remit of that Convention has caused a speedy erosion of Israel’s moral exceptionalism.

This development is creating more room for frank and open criticism of Israeli behaviour in international politics.

Finally, consider justice. Even as Israel’s killing of Palestinian civilians continues as it goes after Hamas fighters, a mechanism of accountability has been put in place.

Recognition of wrongs is the starting point for justice. The cases at ICJ and, potentially, at ICC, mean that evidence of unlawful actions is being collected and analysed.

The genocide case may take years and, in the end, Israel may not be found guilty. But South Africa’s case has been admitted and a clock of accountability has begun to tick.

It is also possible that the ICC warrants will not come — they’ve generally tended to come against non-white, non-Western individuals — and Israeli leaders will not be arrested even if warrants are issued.

However, it would be wrong to ignore the seriousness of the ICC’s charges. They include ‘starvation of civilians as a method of warfare’, ‘wilful killing’ of civilians, ‘intentionally directing attacks’ against a civilian population, ‘persecution’, and — most seriously — ‘extermination and/or murder’. ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan charged Israeli leaders with deliberately committing crimes against humanity. When the crimes are read together, they appear to add up to genocide.

These three sets of developments show that International law has not failed in the context of the war in Gaza. It continues to shape the emerging contours of geopolitics, morality and justice.

A cynical view that reduces international affairs to power politics alone misses the churning mediated by international law in this context — something not seen since the end of World War Two.

Atul Mishra is Associate Professor of International Relations at Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence, Delhi-NCR, India.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.