COP28 signalled the 'beginning of the end' of the fossil fuel era. But more finance and a focus on equity can facilitate adaptation in vulnerable countries.

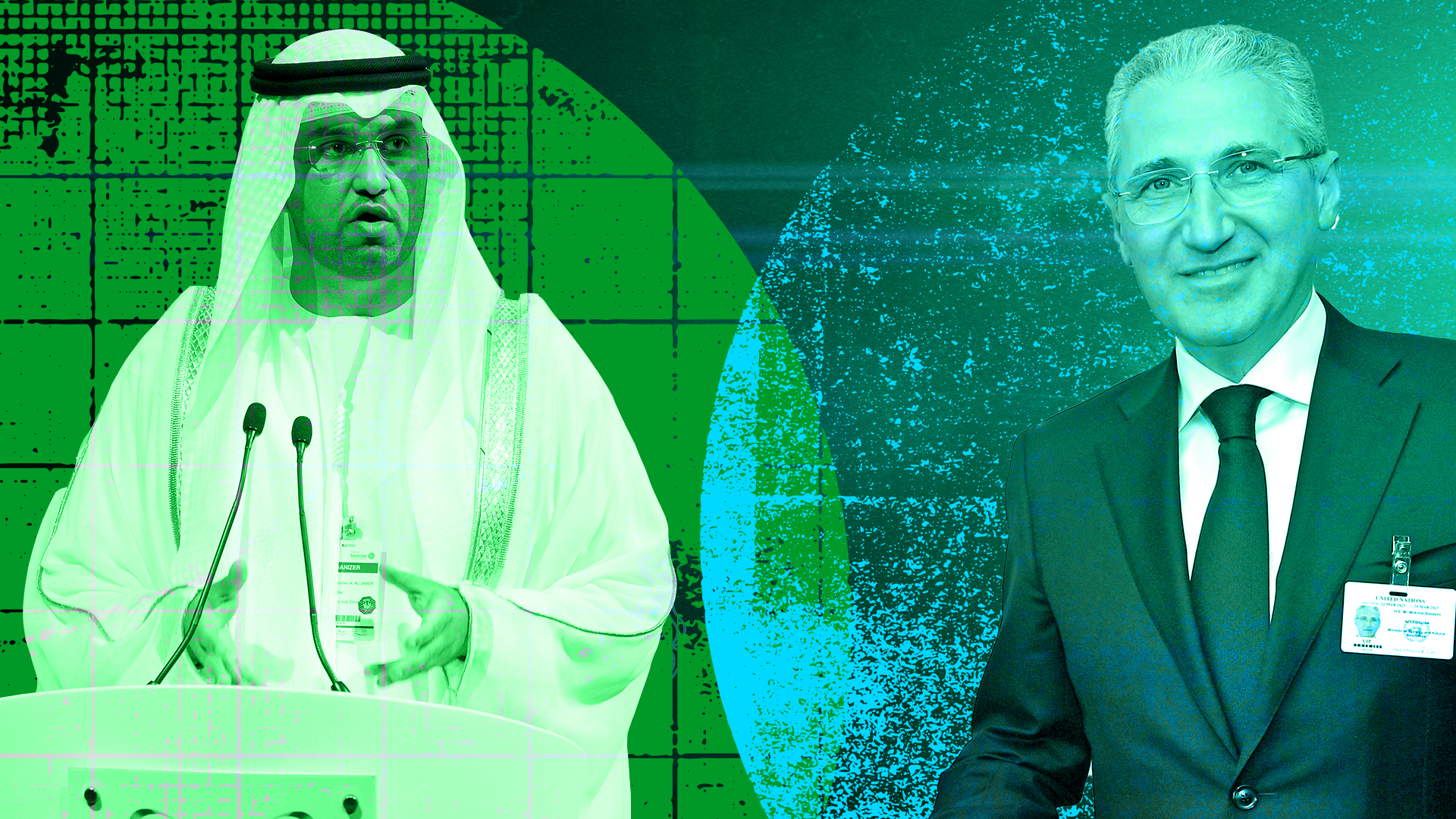

At 2023’s COP28 Summit, Negotiations started on a high note at Dubai’s COP28 Summit in 2023. : Dean Calma/IAEA, Flickr CC BY 2.0 DEED (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

At 2023’s COP28 Summit, Negotiations started on a high note at Dubai’s COP28 Summit in 2023. : Dean Calma/IAEA, Flickr CC BY 2.0 DEED (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

COP28 signalled the ‘beginning of the end’ of the fossil fuel era. But more finance and a focus on equity can facilitate adaptation in vulnerable countries.

November’s COP29 in Azerbaijan does not seem likely to lead to more ambitious climate plans.

With ongoing geopolitical tensions, high interest rates, and upcoming pivotal elections in the US, the UK, and the European Union, countries will have the task of navigating climate goals while dealing with concurrent equity, socio-economic and geopolitical challenges.

At 2023’s COP28 Summit, negotiations started on a high note, as the world finally agreed to move away from fossil fuels. Negotiators from 200 parties came together with a landmark agreement to increase climate action before the end of this decade to keep within the 1.5-degree Celsius target.

But despite the first Global Stocktake finding the world is off-track in meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement, consensus on other key issues remained elusive, including the level of ambition in emission reduction targets.

While some countries committed to aggressive targets in line with scientific recommendations, others stopped short, citing debt and ballooning costs as barriers to pushing for more ambitious goals.

Despite calls for bold action, COP28 lacked clear commitments and timelines for a full coal phase-out. The Least Developed Countries Group, composed of representatives from 45 low-income countries, argued that COP28 outcomes reflected the lowest possible ambition that they could accept.

The need for increased climate finance

UN Climate Change Executive Secretary Simon Stiell called climate finance the “great enabler of climate action”. COP28 had a promising start: The Green Climate Fund reached a record USD$12.8 billion from 31 countries with new pledges from Australia, Estonia, Italy, Portugal, Switzerland and the United States.

But as noted in the First Global Stocktake, this is far from matching the scale of funding needed to address the irreversible loss and damage risks affecting marginalised groups and people living in poverty in the Global South, estimated at USD$116-435 billion in 2020 to $1.1 to 1.7 trillion per year by 2050. These estimates do not include the non-economic loss and damage such as loss of social cohesion, cultural heritage and identity which are impossible to quantify.

The agenda for COP29 is set to focus on the New Collective Quantified Goals on climate finance. This refers to the commitment from developed countries to mobilise from a floor of USD$100 billion per year to address the needs and priorities of developing economies.

Deliberations on the quantity, quality, and what these goals need to address are still underway and were described by Climate Action Network Europe as “slow and unproductive”. COP29 should collectively and decisively come up with new financial goals that are in line with the needs of developing countries.

Equity issues at COP29

There are also equity issues surrounding the upcoming COP.

For one, the Azerbaijani Government nominated an all-male organising committee for the conference, following the longstanding tradition of ignoring the important role that women play in climate action. This resulted in a strong and immediate backlash from the international community, prompting the government to add 12 women to its 41-member committee.

COP29 is hosted in an authoritarian petrostate known for its human rights violations against environmentalists and journalists. Amnesty International and others have called on Azerbaijan to commence meaningful reforms prior to COP29 and place human rights at its core.

Fossil fuel lobbyists might also be granted access to the negotiations, similar to what happened at COP28. The presence of the world’s biggest polluters will have a significant influence on the COP presidency and participating parties.

There is also a worrying trend of some parties attempting to remove the language referencing the special circumstances of least developed countries and small island developing states.

The principle of special needs and circumstances is a fundamental element of the Paris Agreement and is more than necessary to advance climate justice. COP29 should put the needs and aspirations of these two groups at the forefront of proposed solutions.

Calls for peace and financial transparency

Amid the worsening geo-political tensions such as the territorial disputes in the South China Sea and the Israel-Gaza conflict, Azerbaijan is calling for peace and might ask the parties to observe a “COP truce” to prevent future climate-fuelled conflicts.

The President-designate of COP29, Mukhtar Babayev, has also called on low-income countries to be transparent over climate spending to develop trust.

This is all very ironic as the host country itself is accused of discrimination and ethnic cleansing of Armenians in the heavily contested Nagorno-Karabakh region, and is known for its lack of transparency and corruption in its oil and gas industry.

While peace, stability and transparency are certainly important, these should not distract us from our sobering reality: we are not on track with our climate commitments, the impacts of climate change will only get worse, and the rich companies and fossil fuel companies should foot the climate bill.

Babayev claims: “I will build bridges between the diverging north and south to keep 1.5 C in reach.”

One can only hope that this is not empty rhetoric.

A ‘real’ transition away from fossil fuels requires concrete steps to fully stop fossil fuel, adequate financing to support the most vulnerable countries, and preferential treatment for least developed countries and small island developing states.

Until this is done, COP29 and other future COPs may continue to fall short.

Dr Justin See is a postdoctoral research fellow in climate change adaptation from the Sydney Environment Institute at the University of Sydney.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.