Despite alarming headlines, Strasbourg election results suggest a gradual rightward shift in Europe, reflecting long-term trends rather than sudden changes.

European Parliament Strasbourg, France : by Frederic Köberl available at https://bit.ly/3zgwj86 Unplash Lincece

European Parliament Strasbourg, France : by Frederic Köberl available at https://bit.ly/3zgwj86 Unplash Lincece

Despite alarming headlines, Strasbourg election results suggest a gradual rightward shift in Europe, reflecting long-term trends rather than sudden changes.

A falling tree makes more noise than a growing forest. This idea might explain why some observers view alarms about Europe’s rightward shift, following the Strasbourg parliamentary elections, as excessive.

This situation is not new. On the eve of the 2014 and 2019 elections, many polls predicted a disruptive populist wave hitting EU institutions. Both times, election results allayed those fears. Today, the new parliament’s composition suggests a similar outcome.

Despite the uproar caused by results like the Rassemblement National’s victory in France, the political balance of the Old Continent remains largely unaffected. The coalition that has supported the Commission for the past five years retains its majority.

The European People’s Party (EPP) remains central to any majority, with Ursula von der Leyen expected to continue in her role. The opposition is fragmented, echoing the “much ado about nothing” sentiment from previous elections.

However, the landscape does look different if, instead of focusing only on the falling tree, we take a comprehensive look at the growing forest.

The push to the right

Despite stable majorities, the political geography of Europe has changed profoundly over the last 15 years. Although the populist wave has not overwhelmed the institutions, it has slowly pushed the balance increasingly to the right.

The extent of this change is evident when we observe how the composition of the Parliament, the only EU body directly elected by the citizens of the Old Continent, has evolved over time.

Twenty years ago, the EPP held 288 seats; in the next legislature, it will likely have fewer than 200. The Liberal group in 2004 gained 100 seats, while Renew Europe now has only 83.

The most striking change is within the social democratic family, which has seen its seats drop in 20 years from 218 to about 138. This shift has not benefited the radical left or Greens significantly.

Instead, more than 150 seats lost by Socialists and Liberals have moved to the right.

In 2004, the Independence/Democracy Group (IN/DEM) and the Union for Europe of the Nations (UEN), the two main right-wing Eurosceptic groups in Strasbourg, had 22 and 44 MEPs respectively.

Nowadays estimates suggest that the two main right-wing groups, European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and Identity and Democracy (ID), will together have more than 140 MEPs (83 and 58 respectively). It is also likely that a new ‘sovereignist’ grouping will be formed, headed by the Hungarian Fidesz party and composed of other ‘outsiders’ from the existing formations.

Since 2004, the parliamentary weight of the right has more than doubled.

Surveys show that it is precisely the populist right-wing parties that have capitalised on resentment towards the elites and discontent with economic and cultural globalisation.

What next for the Green Deal?

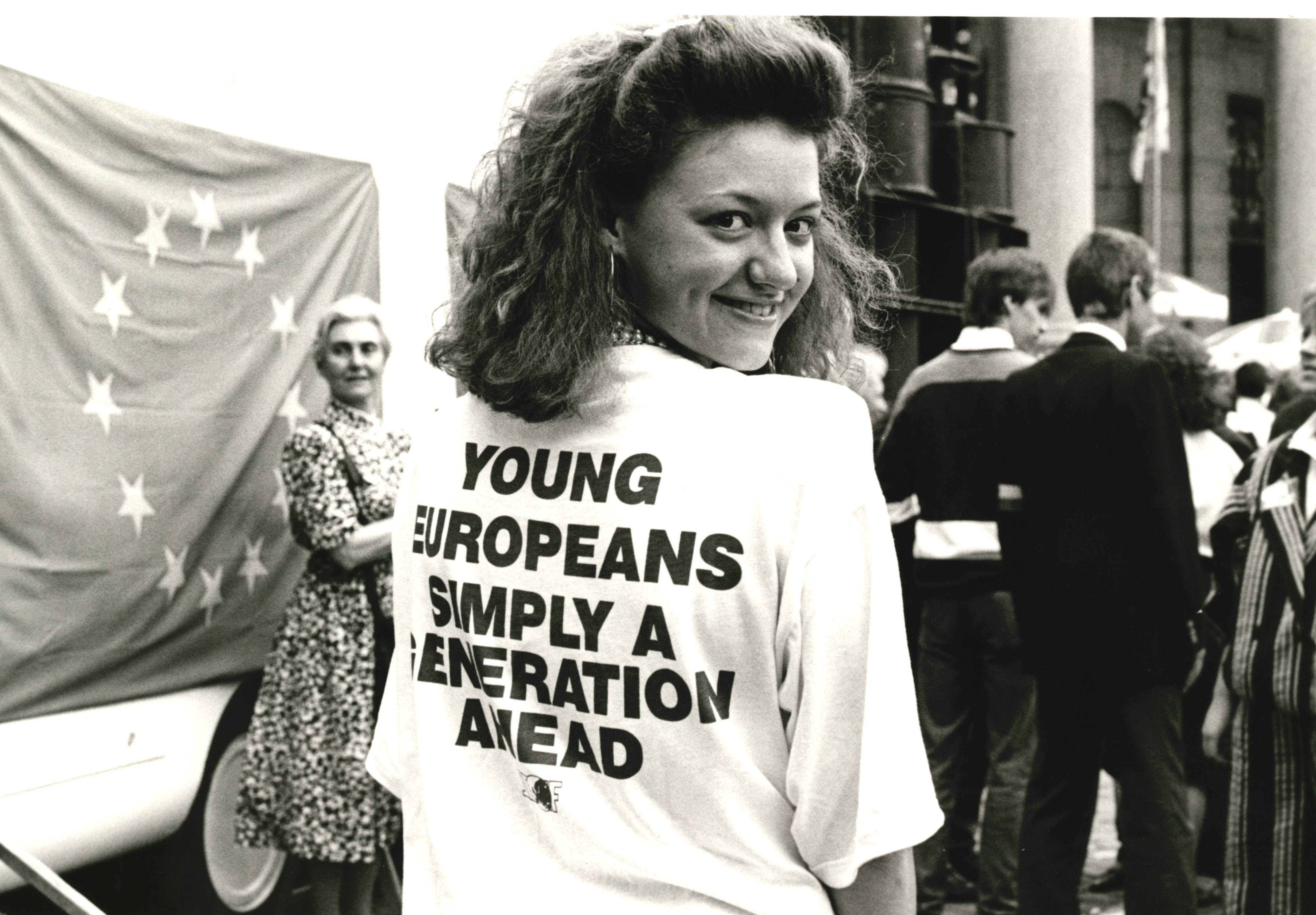

Recent elections show significant youth support for these parties. Over the long term, the ‘growing forest’ is clearly a right-wing one, contrasting sharply with the progressive decline of the European left.

Manfred Weber, re-elected as EPP leader in Parliament, has long aimed to steer the Commission rightward.

This task is, however, very complex. It is quite easy to identify who could be the designated victim of this shift to the right in the Commission. Over the past five years, the Green Deal — launched by the Commission also to gain the support of the Greens — has become the target of criticism from all right-wing “Eurosceptic” formations.

It is therefore likely that von der Leyen’s attempt to win consensus on the right will lead to a significant downsizing of the green transition plan. It is very difficult to imagine what overall project for Europe will emerge from the potential rightward shift of the political balance.

All the right-wing forces included in ECR and ID, as well as parties like Fidesz (currently ‘homeless’ in the Eu Parliament), share Euroscepticism, nationalism, and sovereignism.

Therefore, “utilitarian” bargaining is certainly possible for individual countries. Fratelli d’Italia could guarantee support for the new European Commission if it commits to relaxing the rules on economic constraints regarding Italian public accounts .

Alternatively, the Rassemblement National could reduce its hostility to von der Leyen in exchange for full political legitimacy, recognising Marine Le Pen’s party as a fully democratic actor. Generally, the DNA of various right-wing formations makes them difficult to integrate into a new, compact majority.

Criticism of the EU is often rooted in national interests, dividing right-wing parties on issues like migration, public finances, civil rights, and support for Ukraine. Each of these fractures has deep roots, making them unlikely to be healed quickly or simultaneously.

The rise of the Right is a long-term trend that is already changing the face of the Old Continent. Its direction remains uncertain.

On various national fronts, it could change the functioning of democratic systems, potentially pushing them towards an illiberal drift, as some observers fear, looking particularly at the Hungarian and Polish cases.

Within the EU, the right’s growing influence may weaken efforts to form truly European parties, turning the Strasbourg Parliament into a battleground for national interests.

During a phase of rapidly changing global balances, where the EU will be asked to make important decisions, the result could be a further loss of the Parliament’s political weight relative to national governments and the Commission.

This risks widening the distance between citizens and European institutions, as evidenced by the recent elections.

Damiano Palano is Full Professor of Political Theory, Director of Political Sciences Department at Catholic University of Sacred Heart (Milan) and Director of Polidemos (Center for the Study of Democracy and Political Change).

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.