Cities can be safe havens for endangered plants and animals

Creating better connections between humans and nature is the first step to bringing back animals into our cities.

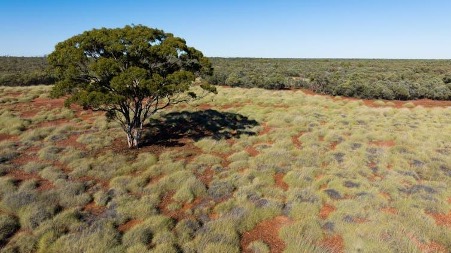

Cities are hotspots for plants and animals that are threatened with extinction. : Patrickkavanagh/Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/patrick_k59/9697721075 CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Cities are hotspots for plants and animals that are threatened with extinction. : Patrickkavanagh/Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/patrick_k59/9697721075 CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Creating better connections between humans and nature is the first step to bringing back animals into our cities.

In the grassy bushland of the Adelaide Hills Barossa Valley, a little fluffy bird, no bigger than the size of a ping pong ball, hops along the unmarked path — the superb fairywren. A proud puffed chest of navy feathers, perhaps from being crowned Australia’s bird of the year several times. The striking blue cap adorning its head in contrast to the muted greens and browns of the land is hard to miss — an encouraging result of conservation efforts by the South Australian government.

But further southwest in Adelaide city lies a far less habitable ground for the little blue birds. Cities are hotspots for plants and animals that are threatened with extinction. Habitats of some of the most critically endangered plants, animals and even entire ecosystems are being destroyed at an alarming rate to accommodate urban sprawl. Australia’s urbanisation has steadily grown since 2002, reaching its highest ever growth rate in 2020. And it’s likely to continue growing as we clear out nature to make room for homes, freeways, car parks and backyard pools.

As a result, Australian species like the koala are disappearing before our eyes. So are ones you may not have heard of like powerful owls, grassland earless dragon, the southern brown bandicoot. Or wild flowers like the sunshine diuris orchids and the button wrinklewort.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Creating urban environments that conserve biodiversity through careful planning, design and architecture can bring back nature into our cities. With some policy rethink and clever designs, cities could be safe havens for species to thrive and recover.

An important first step is to reframe the way nature is considered in urban planning. Rather than considering nature as a constraint, or a ‘problem’ to be dealt with, it can be an important asset and opportunity. It’s a valued resource to be preserved and maximised at all stages of planning and design. This means carefully regulating to ensure the protection of remaining natural assets — from patches of vegetation to single trees. Otherwise it’s too easy for vegetation to be whittled away to make way for development.

Mitigating the impacts of development and creating better connections between humans and nature is the first step in biodiversity-sensitive urban designs. New builds should assess whether there are threatened ecological species in the area, and retain existing native plants and vegetation as much as possible during development.

Working with developers, designers, councils, community groups and Traditional Owners to choose species to target will help with conservation. Species can be chosen on the basis that they are charismatic or culturally significant. Or that they provide an important ecosystem service like pollination. The cities of Melbourne and Adelaide, for example, have specifically chosen vegetation that will improve the habitats of birds like the superb fairywren.

Cities can be hostile places for plants and animals. The next step is to consider how they will have food, shelter and water to survive — away from threats and predators. In many cases, planting native vegetation can provide much needed food and shelter. In addition, new solutions, like biodiverse green roofs, habitat boxes and insect hotels can also provide food and shelter for a range of animals in cities. Stormwater runoff which can negatively impact native plants and animals such as frogs can be mitigated by vegetated swales and rain gardens. Space is highly contested in cities so finding places where vegetation can benefit people and biodiversity is essential.

Installing bird-friendly glass can stop the death or injury of bird collisions and wildlife-friendly lighting is designed to be safe for light sensitive species like moths. Incorporating bird nesting boxes into the external walls of buildings provide safe homes and can encourage breeding. Road underpasses can also provide animal safety from cars.

Nature in cities delivers a raft of additional benefits for threatened species and people. Local biodiversity can create a unique sense of place and is an important opportunity to connect with and build respect for First Nations history and culture. ‘Everyday nature’ delivers a remarkable array of physical and mental well-being benefits and can help make our cities more resilient to extreme weather events, like heat waves, storms and floods.

While remnant vegetation, parklands and waterways will be core elements of the ecological network, biodiversity-sensitive urban design also highlights the potential for the built components of our cities to provide critical resources for other species. Other opportunities to incorporate nature for people and other species include streetscapes, backyards, green walls, green roofs, roundabouts, pop-up-parks, school yards, transport routes and office building courtyards.

Sarah Bekessy has been teaching in Sustainability and Urban Planning at RMIT University since 2004. She leads the Interdisciplinary Conservation Science research group and has recently commenced an ARC Future Fellowship investigating socio-ecological models for environmental decision making.

She received funding from the NHMRC, the H2020 scheme through the European Commission, the Ian Potter Foundation and the Australian Research Council.

Georgia Garrard is a senior lecturer in sustainability in the Office for Environmental Programs and School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences at The University of Melbourne. She is an interdisciplinary conservation scientist whose research addresses the critical challenges of conserving bioidiversity in human-dominated landscapes.

Georgia Garrard receive funding from The Myer Foundation, the Australian Research Council, and the Ian Potter Foundation

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article has been republished for the COP15 Biodiversity Summit. It was first published on October 26, 2022.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Science against the clock” sent at: 26/10/2022 14:47.

This is a corrected repeat.