European elections saw increased turnout and revealed youth preferences, highlighting divides between established and newer democracies.

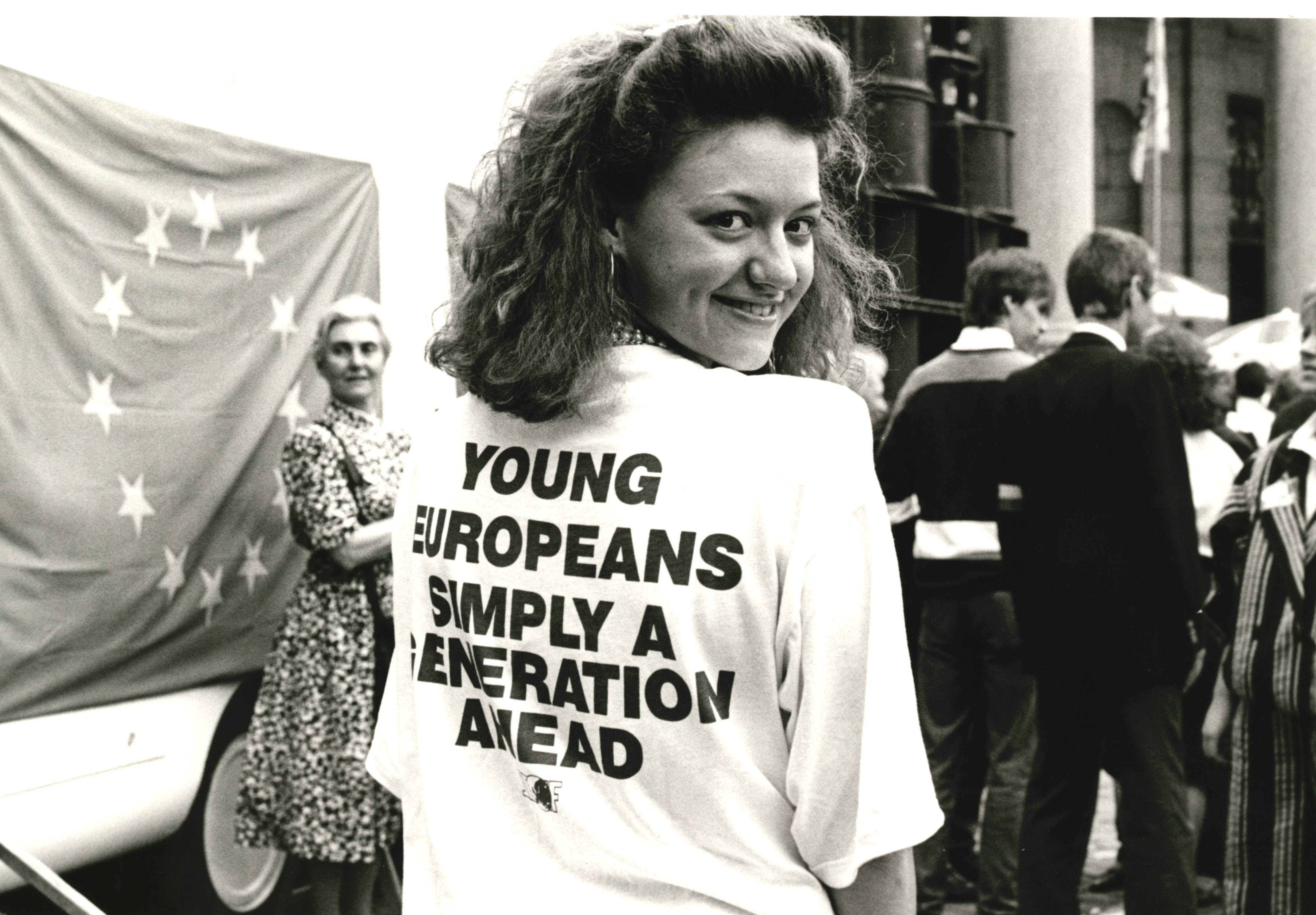

A protester in Brussels, during the European Council, 1987 (Fonds UEF) : European University Institute from Italy, available at https://bit.ly/3W1SY0M CC BY-SA 2.0

A protester in Brussels, during the European Council, 1987 (Fonds UEF) : European University Institute from Italy, available at https://bit.ly/3W1SY0M CC BY-SA 2.0

European elections saw increased turnout and revealed youth preferences, highlighting divides between established and newer democracies.

Voters abstaining from elections is a key indicator of malaise in Western democracies. It signals distrust in the representative system and political elites.

While reasons for abstention vary, the undeniable fact remains: these individuals are not participating in shaping public policies.

Not all scholars agree on this interpretation of abstentionism. Some believe that low voter turnout strengthens democracy by not overloading it with demands and expectations that it cannot fully satisfy. The debate is open and will occupy scholars of democracy for many years to come.

A breakdown of voting data from last month’s European election reveals multiple factors at play.

Despite concerns, voter turnout slightly increased to 51.8 percent compared to 50.66 percent in 2019 and 45.47 percent in 2004.

Turnout disparities among countries were significant: Belgium (89.82 percent), Luxembourg (82.29 percent), and Malta (73.00 percent) had high participation, while Croatia (21.35 percent), Latvia (33.82 percent), and Lithuania (28.35 percent) were the opposite.

Europe’s voting divide

These disparities highlight a divide within the European Union. Established democracies maintain high participation levels, whereas newer democracies show less electoral enthusiasm.

National factors also influence voting patterns and outcomes – both in terms of participation and election results.

A Eurobarometer report published just one month before the last month’s European elections showed that 64 percent of young people intended to vote, while 13 percent said they would not vote, countering the narrative of youth disinterest.

However, there is another fact to analyse: only 38 percent said that voting was the most effective way to make their voice heard. This answer is perhaps even more important than the one about voting because it shows a shift in political engagement of young people.

If, until a few decades ago, political parties were the main channel for participation, and elections were therefore the moment to measure the strategies implemented, this is no longer the case.

Young people want to participate, but in different ways: with posts on social networks, but also through mailbombing, online fundraising campaigns, social activism, although for some minorities street demonstrations remain a way of active participation.

A recent survey conducted in Italy among young people (18-34 years old) revealed a gradual increase in trust in political parties, peaking at 31.6 percent from 8.5 percent in 2012.

The level of trust is low, but this trend is notable, even if it is relative to only one EU country: political parties remain central to elections, essential for representative democracy.

What young people voted for

The ideological dimension of the vote also merits attention. Who and what did young Europeans vote for?

We are not yet in a position to give precise answers, but several trends point to a preference of young people for far-right parties in Belgium, France, Portugal, Germany and Finland, driven by anti-establishment and anti-immigration stances, including among first-time voters.

In contrast, Italian youth lean towards left-wing or centre-left parties.

These data need to be interpreted from a different perspective than the classic left-right polarisation, or at least with new categories of interpretation.

One example may be instructive: in Italy, a significant percentage of young people still agree on the need for a “strong leader” to finally solve the country’s problems.

This is to be considered in relation to this country and its political and institutional geography, which, however, seems to contradict a “leftist” tendency of young people, since the “strong leader” is generally associated with “rightist” electoral profiles.

As for abstention, the European elections show that, overall, there has been no collapse, but participation varies from country to country.

The differences would seem to echo, in part, the distinction between established democracies and fragile democracies.

This distinction is crucial for the future of the European Union because it recalls the delicate ongoing illiberal question: is the illiberal virus also a consequence of low electoral participation? This question sums up one of the most important political topics.

The second aspect that emerges from EU Elections is related to young people’s perception of democracy: the low importance they attach to voting and, at the same time, the great desire to be able to participate and make their voice heard is emblematic.

The question is: are the new forms of participation at least as incisive as voting? It is difficult to provide an answer, but the question must be asked to initiate a non-stereotypical reflection on the future of democracy in Europe.

Antonio Campati is Assistant Professor of Political Philosophy at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart (Milan), Senior Fellow of Polidemos (Center for the Study of Democracy and Political Change) and member of the Editorial Board of Rivista italiana di filosofia politica, Power and Democracy and Dizionario di dottrina sociale della Chiesa. His research interests mainly focus on the transformations of political representation and on liberal and illiberal theories of democracy. He is the author of: La distanza democratica. Corpi intermedi e rappresentanza politica (Vita e Pensiero, 2022) and I migliori al potere. La qualità nella rappresentanza politica (Rubbettino, 2016).

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.