Australia’s ski industry falls victim to declining snowfall

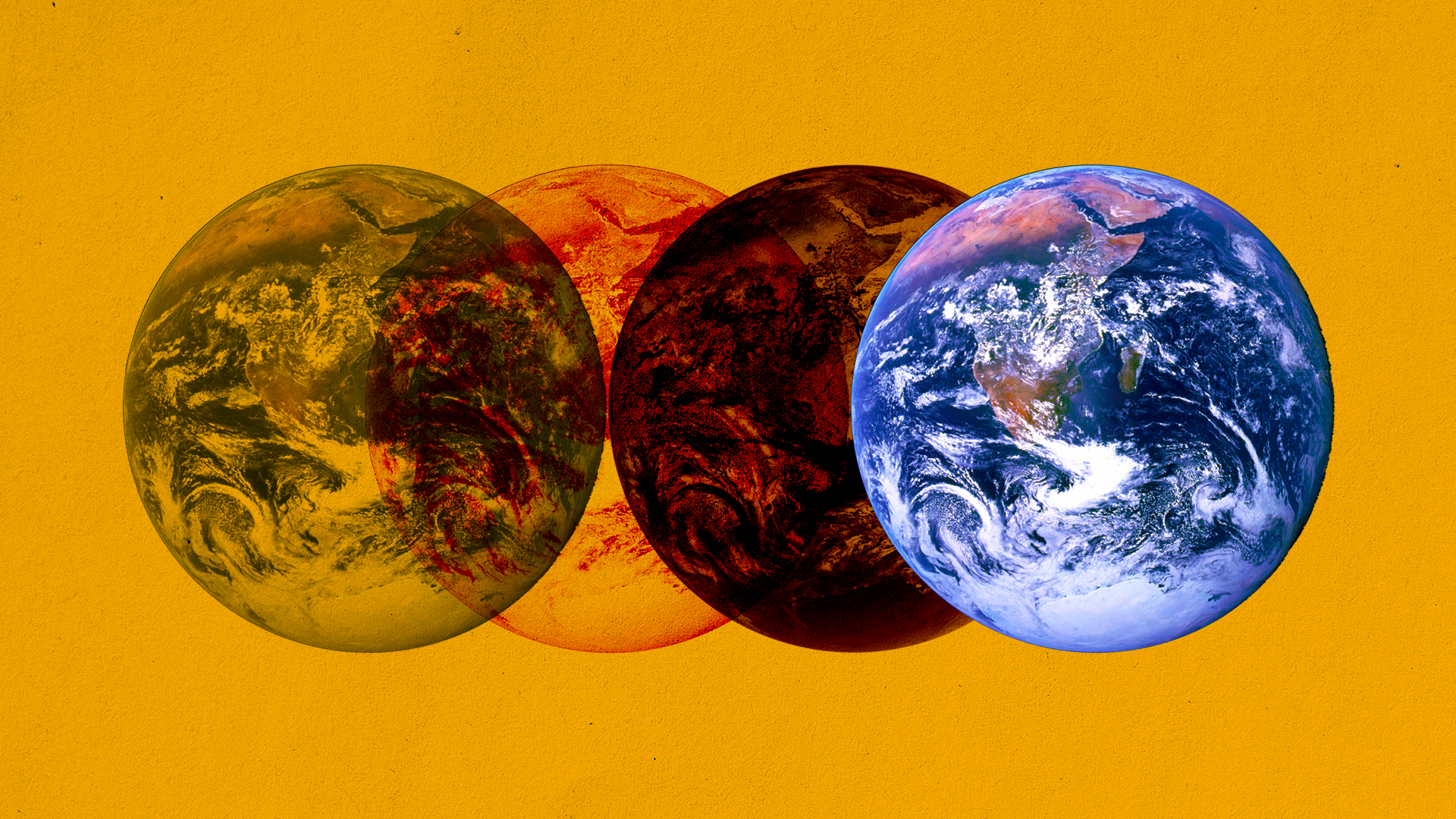

The ski industry will be so quickly impacted by climate change that it's been termed "the canary in the coalmine". Not all hope is lost — but we must act fast.

Australia’s snowsports season will reduce by up to 55 days in a high-emissions scenario. : Maxwell Ingham via Unsplash Unsplash Licence

Australia’s snowsports season will reduce by up to 55 days in a high-emissions scenario. : Maxwell Ingham via Unsplash Unsplash Licence

The ski industry will be so quickly impacted by climate change that it’s been termed “the canary in the coalmine”. Not all hope is lost — but we must act fast.

Australia’s snow seasons are getting shorter, while the nations’ snow cover is decreasing — and Australian ski resorts may be forced to shut if the current level of climate pollution continues, experts warn.

Many alpine resorts in Europe have already closed due to declining snowfall and global warming. Most recently, a large French alpine resort announced in October it would not be reopening, joining a string of about 180 closures since the 1970s.

In Australia, ski resorts may go the same way by the 2050s, when ski seasons will reduce by up to 55 days in a high-emissions scenario, according to modelling by Australian National University (ANU) researchers.

As dire as that sounds, there’s a reason the ski industry is often termed “the canary in the coalmine” of climate change: It faces one of the most imminent and dramatic threats, but will likely be only the first of many to fall victim to climate change.

Also at risk are native flora and fauna in Australia’s high country, regional communities, hydroelectricity plans,and First Nations communities, according to the ANU researchers.

A particularly vulnerable region

The Australian Alps is one of the world’s most vulnerable regions to climate change.

This unique and fragile landscape covers approximately 5,200 square km in south-eastern Australia. More than 85 threatened animal and plant species can be found there, including the mountain pygmy-possum, southern and northern corroboree frog, and the kelton’s leek-orchid.

The alps is also home to many unique species with specific habitat temperature ranges. Unlike other countries, there are limited higher elevation areas many of these species can move to as temperatures rise.

With average annual temperatures in the Australian Alps having already risen by about 1.4 degrees Celsius since 1950, this habitat is shifting.

Warmer temperatures are already leading to more snowmelt. At the same time, average annual precipitation has decreased by around 140mm — which means less snowfall.

Combined, this leads to reduced snow depth, area and duration, reports by CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology explain.

Winter tourism on a slippery slope

The future looks even more dire, according to ANU’s Our Changing Snowscapes report.

The report presents new modelling for ski season lengths — and highlights dramatic impacts for regional communities, inflows for hydroelectricity and the Murray-Darling river basin, high country ecosystems, and First Nations people.

It projects a dramatic decline in ski season length across Australian resorts. By the 2050s, under a mid-emissions scenario, ski seasons could be 44 days shorter (a decline of 42 percent) compared to the baseline period between 1981-2010.

In a high-emissions scenario, this reduction could reach 55 days (a decline of 52 percent), with lower-elevation resorts more dramatically impacted.

In this high-emissions scenario, Victorian alpine resort Mt Baw Baw could have a season length of just one to three days by 2050. Mt Selwyn in NSW would have a season of just 3-8 days, while Ben Lomond in Tasmania’s ski season would be just two days long by 2050.

By 2080, some of the nation’s most famous resorts — including Falls Creek, Mount Buller and Thredbo — may have no ski season at all.

There will also be an increased demand for artificial snowmaking to compensate for reduced natural snowfall. This is projected to significantly raise water and electricity costs for resorts, adding financial pressure and potentially jeopardising their long-term economic viability.

The economic cost

The economic implications of all these changes are significant.

The Australian ski industry currently contributes an estimated $3.33 billion annually to the national economy. In 2019, Victorian alpine resorts alone contributed to approximately 10,000 direct and indirect jobs, mostly in regional areas.

The potential closure or reduced operations of ski resorts threatens thousands of local jobs across NSW and VIC, with significant impacts on regional towns with limited economic diversity.

This local impact reflects a broader global trend. For example, in the United States, the ski industry has lost $US2billion in the past two decades as the result of anthropogenic climate change, highlighting the widespread economic consequences of climate change on winter tourism globally.

Impacts on tourism are not restricted to winter seasons, with Australian alpine resorts that have invested in summer tourism, such as mountain biking and hiking, also facing climate change impacts from increased bushfires and summer storms.

A second aspect of economic concern is the impact on inflows — water flowing in from rain and melted snow — to hydroelectricity generation.

This could impact Snowy Hydro in New South Wales, the Kiewa scheme in Victoria, and the Murray-Darling Basin in Australia’s south-east.

The Basin, sometimes known as “Australia’s food bowl,” receives approximately 30 percent of inflows from the Australian Alps. Projected reductions in rainfall and snowfall will increase water conflict in a part of Australia that’s already politically contested and facing overlapping threats including drought, toxic algae blooms and mass fish deaths.

Climate change is also threatening dramatic ecological transformation of high country ecosystems.

Increased temperatures and changing climatic conditions are already increasing the presence of weeds and invasive animals, They’re also changing the composition of vegetation communities, altering the timing of flowering and migration events, and changing soil and hydrology.

These impacts are projected to worsen. They could result in threatened species extinction, loss of subalpine woodlands (including high-elevation snow gums from insect-driven dieback and bushfire), and irreversible degradation to alpine bogs and fen communities.

Transformations of the landscape will impact everyone with a connection to the Australian Alps, and particularly First Nations people and their connection to Country.

The alps have deep significance to First Nations people as a place for annual celebrations and the meeting place of multiple nations, coinciding with the bogong moth migration.

Although there is a growing body of research about the significance of the Australian Alps to First Nations, there is little work done on how climate change will impact First Nations and their relationship to Country.

Further empowerment of First Nations in the decision making and management of the Australian Alps is vital, with expanding the Indigenous ranger programs being a key opportunity.

What’s needed

Reducing emissions and adapting to climate change is critical to mitigate some of the worst threats facing the Australian Alps.

The Our Changing Snowscape report indicates that keeping global emissions within a low emission scenario could still enable economically viable ski seasons, particularly at higher altitude resorts.

Other recommendations from that report include diversification of tourism to reduce dependence on skiing, with careful consideration of ecological impacts, and collaborative governance with communities and First Nations.

The report highlights that additional funding for natural resource management is essential, for both management to implement “no regrets” actions such as weed removal, invasive species management, and peat bog restoration, but also for developing novel interventions in response to dramatic ecological transformation.

The significance of the Australian Alps extend well beyond their borders. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions at a local, national, and international scale is crucial; the more we can limit the impact of climate change, the easier and cheaper climate adaptation will be, and the better we will be able to preserve the diverse values of the alps.

Ruby Olsson is a social scientist undertaking a PhD with the Fenner School of Environment and Society and the Institute for Water Futures at the Australian National University. Her research examines how natural resource managers respond to ecological transformation, using a case study of snow gum dieback in the Australian Alps.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.