Australia’s reef fish must adapt, migrate or they might go extinct

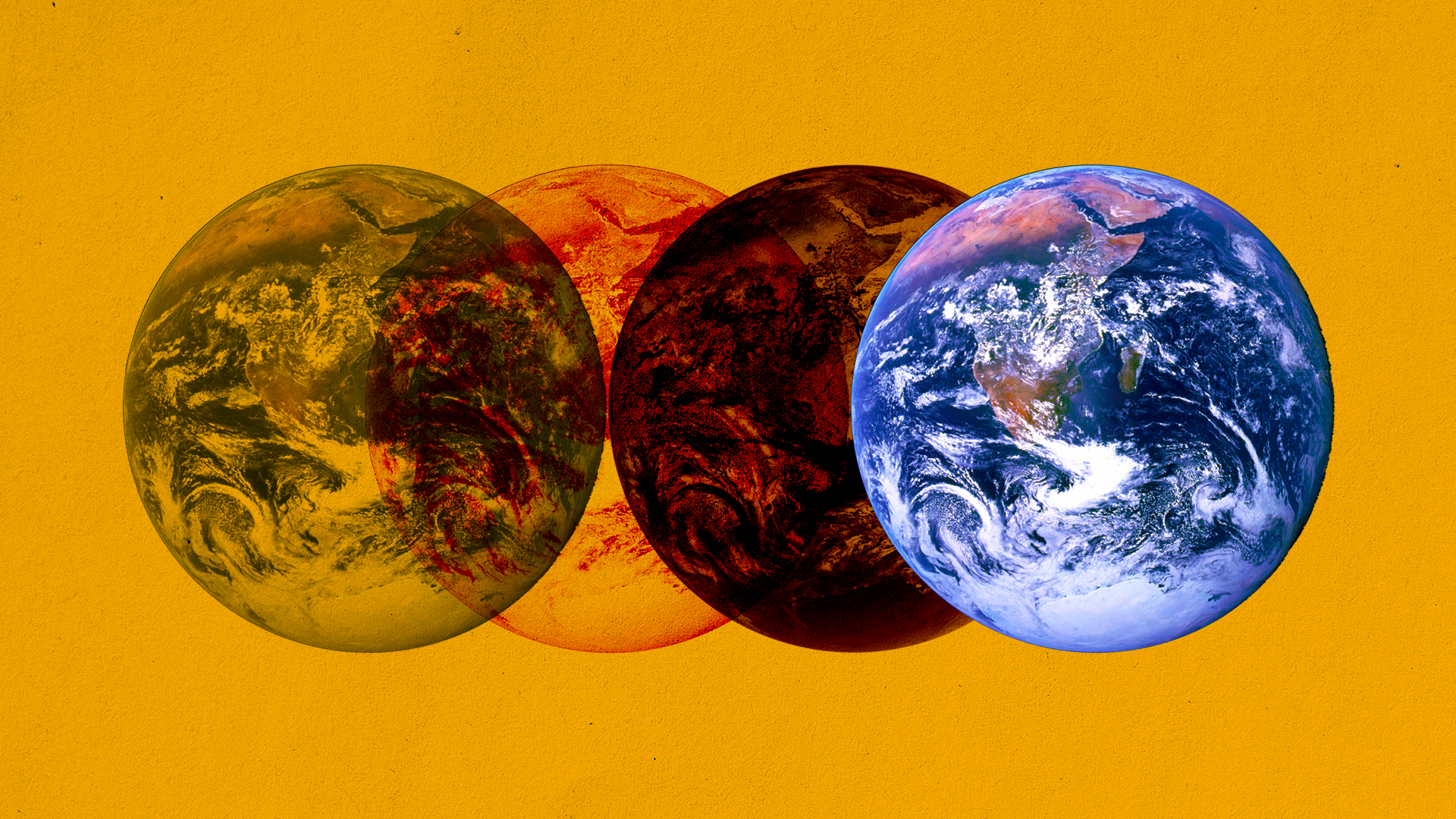

Warming oceans are driving away Australia's reef fish to cooler waters — and it's threatening entire industries and communities reliant on healthy reefs.

Rising water temperatures are expected to shrink fish sizes, lower their nutritional quality and destabilise marine food webs – ultimately threatening food security. : Unsplash: Kristin Hoel Free to use

Rising water temperatures are expected to shrink fish sizes, lower their nutritional quality and destabilise marine food webs – ultimately threatening food security. : Unsplash: Kristin Hoel Free to use

Warming oceans are driving away Australia’s reef fish to cooler waters — and it’s threatening entire industries and communities reliant on healthy reefs.

Warming oceans and stronger currents have already driven at least 150 Australian coral reef fish species — including the black rabbitfish, the threadfin butterflyfish, and the Coral Sea gregory — to more temperate waters.

These impacts of climate change are only expected to intensify over the next few decades, with ocean acidification also expected to gradually kill off corals, kelp and fish.

Dozens of temperate reef fish species, including the red handfish, the Australian mado, and the recreationally targeted luderick, face potential population collapse if they don’t adapt or migrate to cooler waters.

The industries and communities that rely on our oceans for survival are also under threat. So, now is the time to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change on Australia’s marine ecosystems.

Coral bleaching and an exodus of fish

Climate change has already begun disrupting the vital services that tropical and temperate reef fish provide to both humans and the environment.

Marine ecosystems in Australia warmed by more than 1 degree Celsius on average over the past century — triggering widespread coral bleaching, wiping out kelp forests and pushing commercially important reef fish toward cooler, higher-latitude ocean waters.

Current levels of ocean warming and strengthening ocean currents along Australia’s east and west coasts have changed some species’ distributions (known as “range-extensions” to marine ecologists), pushing more than 150 coral reef fish species into temperate waters.

This has created new ecological interactions, with increasing alterations to biodiversity and ecosystem functioning.

For example, herbivorous tropical fish are now overgrazing Australia’s temperate kelp forests, which serve as blue carbon hotspots (vegetated coastal ecosystems that can store and sequester carbon) and are vital habitats for temperate marine life.

Extreme climatic events, such as marine heatwaves, have increased in frequency by 34 percent and duration by 17 percent over the past century, burning up marine food chains in Australia by altering plankton communities to smaller cells less easily consumed by reef fish.

Smaller, less nutritious fish

Over the next 50 years, Australian waters are projected to warm by an additional 3 degrees on average.

Reef fish will need to either adapt to warmer waters, migrate to cooler regions, or face localised extinctions under projected warming scenarios.

Rising water temperatures are expected to shrink fish body sizes, lower the nutritional quality of fish, create hypoxic zones, and destabilise marine food webs — ultimately threatening the food security of Australia’s coastal communities.

And while marine heatwaves are already taking place, the future looks even more challenging.

Under a low-carbon-emissions scenario, extreme marine heatwaves are expected to occur every 15 years, while under a high-emissions scenario extreme heatwaves will occur every year from 2060 onwards, with the Tasman sea forecast o being locked into a permanent heatwave state from 2080.

These heatwave events will likely cause further disruptions to marine food webs, forcing coral reef fish to move south in search of cooler waters, increase coral bleaching and mass fish mortalities events in Australia’s marine ecosystems.

As waters warm — and reef fish continue to shift poleward, or to deeper waters, in search of cooler habitats — industries and communities that rely on healthy reefs will also suffer.

Fisheries-dependent communities may be forced to follow the migrating fish, leading to the displacement of people and loss of livelihoods in both Australia’s economically important fisheries and aquaculture sectors (with a gross value of $2.5 billion per year).

This will strike a heavy blow, too, to Australia’s tourism industries — including those that rely on the Great Barrier Reef, which alone contributes $5.7 billion annually in tourism value.

Acidic oceans a looming threat

Another major threat is ocean acidification, often referred to as the “evil twin” of climate change.

Ocean acidification — a gradual reduction in the pH of the ocean — is primarily caused by uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2) by the ocean from the atmosphere.

While its effects on Australia’s marine environments have yet to be experienced — in contrast to already-occurring significant ocean warming — they are looming.

By 2100, acidification and warming could drastically alter reef habitats, degrading and shifting both tropical coral reefs and temperate kelp forests to ecosystems increasingly dominated by turf algae species.

While this might slow the tropicalisation (establishment of tropical fish in temperate ecosystems) of temperate fish communities, it can have severe consequences for fish communities in their native ecosystems.

The gradual demise of habitat-forming species such as corals and kelp as a result of ocean acidification could also lead to less resilient reef fish communities, loss of biodiversity and increase of a few ‘winner’ generalist species.

These simplified fish communities would be more vulnerable not only to climate change but also to human-induced stressors like eutrophication, sedimentation, and overfishing.

Can we mitigate the worst impacts?

Despite these grim prospects, there are still opportunities to mitigate the effects of climate change on marine fish communities.

Promising research on keystone marine species has already revealed heat-tolerant corals and fish that could help preserve parts of coral reef ecosystems.

However, we still know relatively little about how reef fish might be already pre-adapted to rapid climatic change expected in the coming decades.

While scientists may succeed in rapidly evolving some heat-adapted fish species, it is unlikely that reef fish communities in Australia or globally will be able to cope with both concurrent climate change and other human-induced stressors like sedimentation, eutrophication, pollution and overfishing.

To protect coral reef fish, conservation efforts and policy reforms must reduce these additional pressures and preserve marine habitats, giving reef fish a better chance of survival against the threat of climate change.

While climate change has already caused significant damage to Australia’s coral and temperate reefs and their inhabitants, there remains hope.

Continued research, conservation efforts, and proactive policies could provide the resilience needed to safeguard the ecological, social and economic importance of reef fish for future generations.

Prof Ivan Nagelkerken is a professor in marine ecology at the School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide. He works in temperate and tropical coastal ecosystems, with a special focus on fish.

Dr Angus Mitchell is a postdoctoral research associate in marine ecology at the School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide. He works on fish community responses to climate change, with a special focus on understanding the resilience of fish to ocean warming and acidification.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.