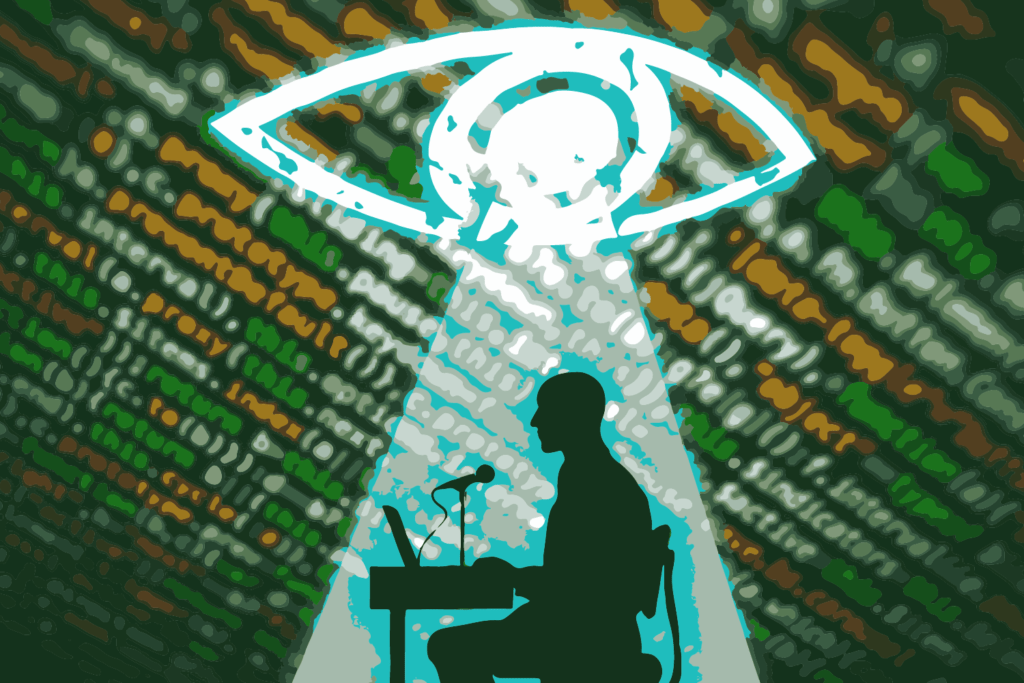

Indonesia's political regime may have changed but pressure on the media has not faded away thanks to new tools and techniques.

The future generation may miss out on good quality journalism. : dwi rahmanto

The future generation may miss out on good quality journalism. : dwi rahmanto

Indonesia’s political regime may have changed but pressure on the media has not faded away thanks to new tools and techniques.

In the pre-digital autocratic era, Indonesian state officials controlled the media through direct censorship, advertising and strict media policies. The government could control the media by selectively deploying its annual advertising budget.

Now, in the digital age, opportunities to control journalists have expanded. Social media ‘buzzers’ and partisan digital influencers are key players in challenging the work of media professionals. Buzzers influence others via social media, enliven online conversations through their tweets, voice their interests and get paid for their posts. They are formally or informally recruited by political leaders as well as the ruling administration.

In step with the massive growth of digital media, digital-based pressures on journalists are on the rise, along with hate-speech malware and cyber espionage. The authorities secure their political power by deploying cyber troops to limit journalistic efforts to produce critical news

In a February 2021 survey of 125 journalists by Indonesia’s Independent Journalists Alliance (AJI), 16 percent of respondents said they had experienced a digital attack; 60 percent of these were related to the journalists’ COVID-19 coverage. The coverage confronted a political scenario to build an image of a strong government facing the global pandemic.

Journalists using digital platforms face various digital threats, including doxing and surveillance, fake domain attacks, forced exposure of online networks, and disinformation. Doxing is the online publication of private or identifying data about an individual, typically with malicious intent. Meanwhile, national-security apparatuses and state-sponsored buzzers use surveillance – the monitoring, interception and retention of information – to track journalists and media outlets that are critical of the government.

Hacking, doxing and surveillance were all used in an attempt to control Tempo magazine between 2015 and 2021. In that period the magazine faced online abuse over its investigative journalism into the acting political powers.

On 21 August 2020, for instance, hackers targeted Tempo.co after reports that artists and celebrities were being paid to promote the government’s Job Creation Law. Tempo’s homepage was hacked and changed with accusations that it was promulgating fake news (referring to its previous investigation of the network of buzzers supporting President Jokowi’s Job Creation Law).

Action was also taken by buzzers in response to Tempo’s political news allegation that the president was attempting to establish a political dynasty after his son Gibran Rakabuming Raka and son-in-law Bobby Nasution contested (and won) mayoral races in Solo and Medan. One group — calling itself Zone Injector — gained control of the homepage and replaced it with the phrase “we warned you, but you did not respond to our good intentions”.

Shinta Maharani, a senior Tempo journalist in a personal interview in May 2021, said that she had experienced hacking on December 24, 2020, after writing a report on the allocation of social assistance; her email, social media, and instant messaging accounts were all hacked. In responding to these abuses, Tempo stood by its journalistic principles and avoided criticism based on hatred or political motives. Tempo also organised mitigation measures for its journalists by offering safe houses to protect them from physical attacks and collaborated with law advocates to handle lawsuits leveraged by state-sponsored actors.

The Indonesian government initially welcomed democratic media principles through a series of pro-democratic media laws, such as the 1999 Law on the Press and the 2002 Law on Broadcasting. When these pieces of legislation were passed, the authorities shared the vision that media policies were necessary to guarantee journalistic independence. However, when the new government was formed, this shared vision was challenged by the re-emergence of state-controlled culture in public media, monopolistic private media ownership, and the rapid rise of paid political cyber troops.

The Press Law offers protections to journalists, but the Information and Electronic Transactions Law (known as the ITE Law) contains articles that threaten journalists with imprisonment – indeed the law has been used to support direct attacks on them in the last 10 years. The ITE law limits online journalistic practices by threatening journalists with up to six years’ imprisonment or fines of up to one billion IDR (US$106,000) for online defamation.

SAFEnet, a digital rights defender throughout Southeast Asia, notes that at least 14 charges were brought against media organisations and journalists between 2008 and 2020. Further, SAFEnet says that revision of the ITE Law, discussed by Indonesian policymakers between 2020 and 2021, could provide the government with a tool to control news media and once again promote violence against journalists.

To counter these attacks, journalist associations and the Press Council of Indonesia have filed police reports, exposing the attackers and protecting their own sources from further online victimisation. The AJI monitors doxing attacks on journalists, and notes that they usually result in persecution. The AJI and other non-profit press freedom agencies have joined the Committee of Journalist Safety (Komite Keselamatan Jurnalis), which has formed a crisis centre to protect and provide legal assistance to victims of harassment.

A comprehensive regulatory scheme is required to protect journalists, end impunity and manage press freedom in Indonesia. Regulations that govern each sector (press, broadcasting, internet) are often contradictory, so revisions there will not be helpful.

A special law for journalist protection is needed to support journalist safety. An anti-disinformation law is also urgently required, as are revisions to the ITE Law so that it can properly provide protection against digital attacks.

Masduki is an Associate Professor and researcher in the Department of Communication, Universitas Islam Indonesia, Yogyakarta. He is a member of several advocacy organisations such as Media Regulation and Regulator Watch (PR2Media), AJI Indonesia, the Public Broadcasting Clearing House of Indonesia, and the Society of Concerned Media Yogyakarta. His work focuses on public-service media systems and journalism studies, comparative media systems, digital media policy and activism. Dr Masduki declared that he has no conflict of interest and is not receiving specific funding in any form.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Journalism under digital siege” sent at: 02/05/2022 11:59.

This is a corrected repeat.