Pakistan faces a wave of problems on multiple fronts, but its growing debt can no longer be overlooked as inflation soars and foreign reserves crumble.

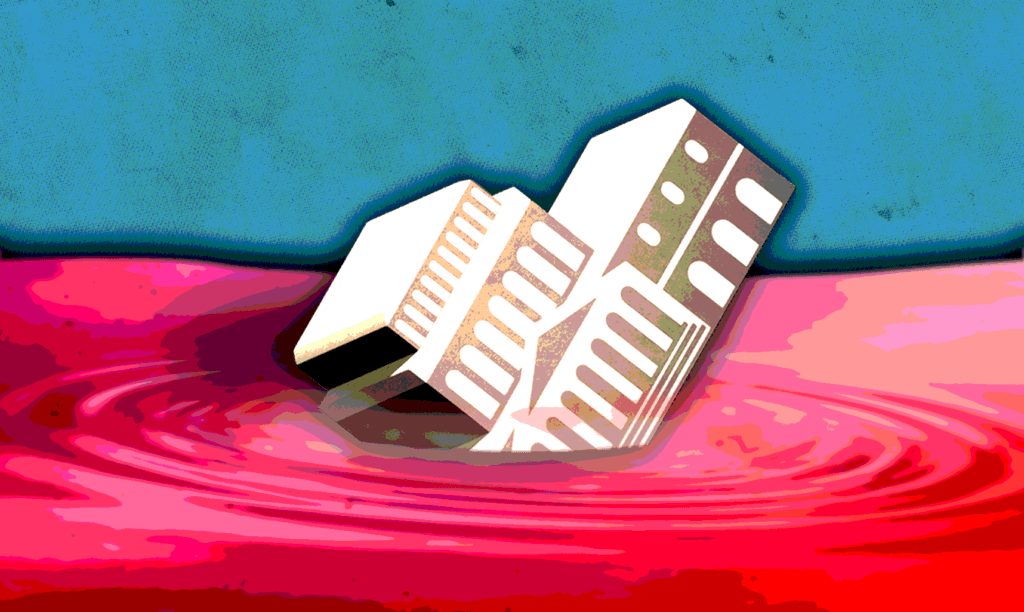

Pakistan continues to develop a dependency on aid and loans. : Dan Casperz/DFID, Wikimedia Commons CC Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic

Pakistan continues to develop a dependency on aid and loans. : Dan Casperz/DFID, Wikimedia Commons CC Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic

Pakistan faces a wave of problems on multiple fronts, but its growing debt can no longer be overlooked as inflation soars and foreign reserves crumble.

Pakistan is on the brink of default and waiting for a miracle — running from pillar to post to find a messiah which can right its teetering economy.

The world’s fifth most populous country faces a wave of problems on multiple fronts ranging from political instability, climate change and an economic crisis that can push it off the same cliff as Sri Lanka.

Intense floods not only inundated Pakistan’s land but drowned its fragile economy just as it was recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The country’s debt has become unsustainable, according to a new study by the Asian Development Bank Institute, To borrow or not to borrow: Empirical evidence from the public debt sustainability of Pakistan. The Damocles sword of debt default is hanging over its head, affecting its import-dependent economy and having far-reaching economic and social consequences.

Pakistan’s external debt and liabilities are almost USD$130 billion — 95.39 percent of its GDP. The cash-strapped country has to return almost USD$22 billion over the next 12 months — a total of USD$80 billion in the next three-and-half years — when its reserves are only at USD$3.2 billion and its economic growth rate a mere 2 percent.

Now the country spends almost half of its federal budget on debt servicing. Although the Pakistani government has implemented measures to reduce the debt burden, including fiscal consolidation, privatisation of state-owned enterprises and reforms to the tax system, it is not enough in the backdrop of skyrocketing inflation.

Inflation is at its highest in 48 years, currently sitting at 27.6 percent. In January 2023, food inflation reached 42.9 percent compared to 12.8 percent last year, leaving millions struggling for their daily meals. The central bank had also raised interest rates to 17 percent, choking business activities and economic growth.

The Pakistani Rupee is Asia’s worst-performing currency after losing 65 percent of its value since last year. The country’s foreign reserve can only cover the necessary imports to keep the country functioning for three weeks.

Huge debts are a result of historically damaging policies, pressure on fiscal imbalance and notably, the balance of payment crisis. To cope with it, Pakistan continued to develop a dependency on aid and loans, including 22 International Monetary Fund programs. The exponential debt accumulation, spent on defence, infrastructure projects and servicing interest payments, pushed successive governments to rely on budget deficits, further exacerbating the situation.

Successive governments have failed to make any structural reforms to bring it out of the vicious cycle of borrowing. Over the years, it has been running a budget deficit of more than 8 percent for which it requires additional financing in the form of taking on new loans.

Every year, the country faces a trade deficit of around 40 percent. Its exports are stagnant while imports increase exponentially.

Remittances — considered a lifeline of the economy — are also falling primarily due to the currency peg policy of the government. For instance, an unannounced exchange rate cap pushed many overseas Pakistanis, particularly from Gulf countries, to remit via the grey (Hundi) market, which offered higher rates than the formal channels. According to the finance ministry, remittances fell 11.1 percent compared to last year.

Similarly, the already low foreign direct investments have further decreased by 58.7 percent. Its low foreign exchange reserves and high deficits show that the country is walking on a double-edged sword, leaving very little space for external shocks.

According to the United Nations Development Program calculations, Pakistan’s lavish spending habits are at 6 percent of GDP or USD$17.4 billion on elite privileges in the form of cheap input prices, tax breaks or preferential access to land and services to feudal landlords, the corporate sector, powerful military members and the political class. It is also (mis)spending between 8 to 12 percent of its GDP every year on its loss-making state-owned enterprises, according to the World Bank report, Hidden Debt.

If the country uses its limited resources prudently, it can bring the economy out of hot water. There will be devastating implications for the Pakistani people and across the region, if a nuclear-capable nation defaults on its payments, fails to correct its direction, and does not restructure its debts.

Developed countries should provide some breathing space to the flood-hit country, which according to the World Bank assessment, incurred economic losses of USD$30 billion from floods and need a further USD$16 billion for reconstruction.

Short-term measures will only divert the current fiasco and stringent long term structural reforms are what Pakistan needs to stay afloat. Policymakers must continue to implement fiscal reforms and encourage foreign investment and export sectors to ensure that the debt burden is reduced and that the economy can grow and sustain itself.

First, measuring to tame the augmenting debt is a sustainable and resilient GDP growth rate of 8 to 10 percent. The government has to grow its surplus by controlling expenditure, which is possible by introducing competitiveness and reforming the tax system.

Pakistan’s tax system is regressive — burdening low income taxpayers — and more than half of its taxes are indirect. For example, from sales tax and customs duty. The agriculture sector is not taxed properly and agri-based products account for 60 to 70 percent of the country’s exports yet its share in tax is only 0.02 percent.

Diversifying Pakistan’s export base can reduce pressure on the Bank of Pakistan and help reduce the trade deficit. Creating a favourable business environment can help increase business competition, reduce budget deficits and a dependency on handouts. The privatisation of loss-making state-owned enterprises may also help.

If the country is willing to save itself from future defaults, it has to abolish elite privileges before it’s too late for everyone.

Wajid Islam is an Economics lecturer at Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Technical Education and Vocational Training Authority Pakistan. He can be reached at wajidislam01@gmail.com or Twitter: wajidislam0

Junaid Ahmed is a senior research economist at Pakistan Institute of Development Economics and senior lecturer at Westminster International University, Tashkent. He can be reached at, junaid.ahmed@pide.org.pk

The research has been published and commissioned by the Asian Development Bank. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Governments in the red” sent at: 24/02/2023 10:04.

This is a corrected repeat.